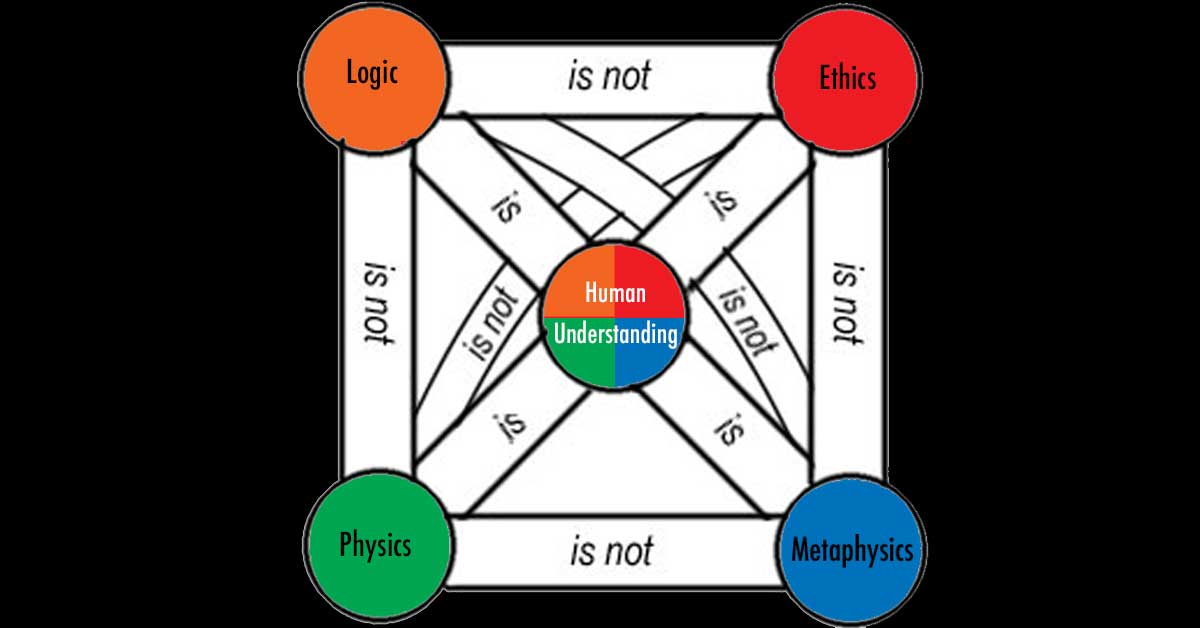

The Spheres of Human Understanding

The Fundamental Principles of Human Understanding, and the Primary “Categories” of Human Knowledge: Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics

The Basics of the Categories of Human Knowledge and Understanding: The Logic Behind the Categories and a Summary of the Categories

All knowledge, all human understanding, can be said to be of four types: physical (empirical), logical (reason), ethical (philosophy in-action), and metaphysical (pure philosophy).

These four types are the primary categories of human knowledge/understanding. We explain the logic behind this theory below, showing how it relates to the Greek concepts of physis, logos, ethos, and pathos), the categories of Aristotle, and the general theories of knowledge of figures like Kant and Hume.

First, let’s start with the logic behind the primary categories (our fundamental categorical classes of human knowledge, physical, logical, ethical, and metaphysical).

TIP: Learn more about “the categories” (and category theory) in general.

A Quick Theory of Knowledge to Allow us to Understand Our Primary Categories (or Spheres)

To create general categories in which we can place all human knowledge, we can state the following closely related judgments:

- Human knowledge is everything that can be known for sure or understood to any degree via experience or thought.

- All knowledge that we can know directly via our senses is empirical, and all knowledge that we have to conceptualize is rational.

In simple terms that gives us two basic categories:

| Empirical / Material (Based on Experience) | Rational / Formal (Based on Ideas) |

|---|---|

| Physics (Empiricism) | Logic (Rationalism) |

Furthermore, the following statements are also true:

- All knowledge is either based on tangible and material things we can sense directly (ex. a rock or an action), or is based on something intangible and formal (AKA “pure“) that we can’t sense directly (ex. a thought, an imagined idea or moral sentiment or feeling, or the will to act).

- There is both formal and material knowledge that applies to the world outside of us, and both formal and material knowledge that applies to the world inside of us.

- All knowledge that applies to the world around us can be called natural philosophy (like math and science; both logic and physics are of this category), and all knowledge that applies to our sentiments, imagination, or actions can be called moral philosophy (like the feeling of love, the concept of a Deity, or acting on Duty; this category contains ethics and metaphysics).

A table that illustrates the four basic categories looks like this:

| Spheres / Categories | Empirical / Material (Based on Experience) | Rational / Formal (Based on Ideas) |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Philosophy (Based on Experience) | Physics (Empiricism; all physical things) | Logic (Pure Logic and Reason) |

| Moral Philosophy (Based on Ideas) | Ethics (Philosophy-in-Action; free will) | Metaphysics (Pure Philosophy; sentiments and imagination) |

Another way to phrase this is that every concept or judgment that can be held within the grey matter of the human mind is either related to:

- A physical thing and its motion (all physical objects and the cause and effect of Newton’s physics); The material one that relates to the body.

- A logical thought, rationalization, or conceptualization. The purely formal one that relates to mind.

- A “metaphysical” thing such as a feeling/imagination/morals. The category that relates to the “soul.”

- The intentions behind the purposeful action of a thing (the choices and customs behind our conduct born from values, rules, and free will).

The category of things is called physics, the category of thought is called logic, the category of action is called ethics, and that category of imagination and feeling about that which isn’t purely empirical can be called metaphysics.

Sure, we can consider the empirical aspects of emotion (“the impressions of passions and sensations”) or cosmology (speculation about the universe), but, in terms of this model, we are going to describe those things as a mixture of physics and metaphysics; what I call “The Physics of Metaphysics” and “the Metaphysics of Physics.”

The same logic goes for ethics which, as it deals with human action as an ends, also deals with a mix of categories.

Consider, ethics is a purely formal thing, as it considers thoughts and feelings, but it has material results (the results of human action born from free will or custom are empirically observable, and thus that aspect relates to material physics). Other aspects of ethics include moral judgments of actions (which relate to metaphysics and logic), and logical rule-sets (which relate to logic).

Suffice to say, each category has its complexities.

With all of that in mind, we can (extrapolating on the above ideas) consider both formal and material, and empirical and rational, aspects of each category (thereby creating a total of 16 categories) to help deal with “mixed” concepts; more on that below.

Specifics aside, the concept here is that by taking the concept of human knowledge and pairing it with the concept of the empirical and rational (and material and formal) we can generally create four possible categories or “spheres of knowledge/understanding” (from which many more can be extrapolated using the same logic).

Because we founded our logic on empirical proof (and notably borrowed theories from the greatest minds of all time like Aristotle, Locke, Hume, Kant, and Mill), and rationalized from there, we create a solid model (a theory) for categorization.

Once you understand the basic categories, then the complex categories can be extrapolated and a basic theory of knowledge can be used to organize concepts, make judgments, and rationalize further (they can be used in the art/science of logic and reason).

With that said, this page isn’t about everything that arises (our page on the basics of a theory of knowledge is), it is about the four general categories above and how to build on them.

So let’s discuss the categories in more detail.

TIP: These aren’t only the spheres of human knowledge, but they are also the spheres of human experience (noting that we can only experience the purely rational and metaphysic via our imagination).

The Greeks, Kant, Hume, Locke, Kierkegaard, and the Spheres of Human Understanding: Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics

Above I noted that we were borrowing this theory from others, or more specifically, we are synthesizing and playing off of their theories to create a somewhat unique theory.

The Greeks, Kant, Hume, Locke, and to some degree Mill on Comte and Kierkegaard, and other “giants of human understanding” all agree that the core three categories expressed by the Greeks, that is Physics, Logic, and Ethics (physis, logos, and ethos), are generally suitable categories for any good theory of human understanding/knowledge (that is, they are generally suitable categories for creating a model with which one can categorize all human knowledge).

With that in mind, Kant [essentially] argues for a fourth term in his masterwork Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals, the Aristotelian term metaphysics (which contains knowledge that is “pure philosophy,” that which “might be” and/or “ought to be,” and the spirit of pathos; this is also expressed by Hume, Mill, Comte, and Kierkegaard in their own ways under names like theology, metaphysics, and religion).

Specifics of other theories aside, from the categorization noted above we can create a simple theory/model of the “four fundamental principles [or spheres, or categories] of human understanding”: physical (empirical, what is), logical (pure reason, logic-and-ethics in-thought), ethical (morals-and-ethics in-action; AKA that which involves human action born from free-will and informed by the physical, logical, and metaphysical), and metaphysical (pure metaphysic morals, practical philosophy, pure philosophy, sentiments, sensations, and what should be).[1][2]

Now that we have the origin story of the categories and the logic behind them covered, the rest of this page will be about how we can add nuance to, and work with, that theory to categorize all human knowledge.

Ancient Greek philosophy was divided into three sciences: physics, ethics, and logic. This division is perfectly suitable to the nature of the thing; and the only improvement that can be made in it is to add… [metaphysics]. – Kant Fundamental Principles [AKA Groundwork] of the Metaphysic of Morals

TIP: Human knowledge here means that which can be known/understood (not just empirically and externally via the senses, but even if only theoretically or internally and without certainty). By most measures, we can be “positive” that we know more about a rock than a moral, empirically at least. That is unless our senses are tricking us. With that said, we don’t just want to categorize what we can know empirically, we want to categorize EVERYTHING we can understand to any degree.

Why is the term “Sphere” used? For our purposes, the term sphere means a category and/or a collection of categories and properties (AKA a categorical system). The term “sphere” is a good synonym for this type of system because it gives a visual of a three-dimensional object that can connect with other spheres and relate to other spheres while remaining its own entity. It also lines up nicely with semantics, for example, if I say “in the sphere of physics,” people know I mean “on the subject of physics” or “pertaining to the category of physics.” Practicality aside, it is really just a “turn of phrase” that prevents our extrapolation of the Greek and Kantian theories of categorization from being confused with other already defined theories.

How to Understand the Properties of the Fundamental Categories and Spheres of Human Understanding

Now that we have the basic four-category model down, we can build on it, explain the logic behind it, and discuss its application and aspects.

Summarizing the Overarching Fundamental Categories as Natural and Moral Philosophy

Adding to the above theory, we can consider that these categories can be grouped into two categories (natural and moral philosophy), and of course a single category (human knowledge).

Thus to state this again,

Natural Philosophy contains physics (here understood as all physical things, not Newton’s physics, but all material objects that form the aesthetic) and logic (pure reason like the pure practical reason of mathematics and theoretical physics) and Moral Philosophy contains ethics (like a lawyer’s rule-set, anything that relates to human action, especially the actions we consider “ethical”) and metaphysics (the potentially unprovable pure morals behind the lawyer’s rules; pure philosophy, the metaphysical aspect of sentiments, and the non-physical or logical factors our ethics is based on).

With that said, a question you might be asking is, “what is the logic behind this aside from trusting the Greeks?” Good question, hopefully, the bit on experience and thought covered this a bit above, but let’s return to it.

The answer lies in the concept of the material and formal.

The Material and Formal and Empirical and Rational

From here we can expand this concept in a few ways.

This can get a little complex, so make sure to follow each point of logic below carefully for a full picture.

Firstly, we can say each category discussed above (so human knowledge, natural and moral philosophy, AND each of the four primary categories) can be considered as and being sub-divided into

- Material knowledge, which concerns some physical object (i.e. that which we can confirm directly via the senses or measurement), or

- Formal knowledge, which pays no attention to differences between objects, and is concerned only with logic and reason (i.e. that which we can’t confirm directly with the senses or measurement).

Here we are making the simple distinction of that which is directly knowable and that which isn’t, but we can also consider this as “that which is external to the human experience” (either directly or with measurement tools) and “that which is internal” (and is thus not directly knowable externally with certainty).

Consider,

- Intuition describes anything that can be understood immediately, without the need for conscious reasoning (whether it arises internally, like an emotion, or externally, like a rock).

- Conceptualization describes anything that requires some degree of rationalization (like a happy rock).

When we intuit feelings, sensations, and passions we know them directly, but they aren’t purely empirical and material things (they have an aspect of the formal to them). Likewise, when we conceptualize an object that could be real based on experience, it is not purely empirical.

Based on those parameters we can state a few things:

- The physical and ethical are “empirical/material” knowledge, in that they deal with that which we can confirm empirically (either directly or indirectly with our external senses), and the logical and metaphysical are “formal/rational”, in that they are “purely” non-material and cannot be sensed directly with the five senses nor indirectly with testing, they can only be confirmed rationally.

- Despite that, the physical and logical are of the overarching “empirical/material” category Natural Philosophy, as we are talking about things that relate to real physical and logical “earthly” objects, and the ethical and metaphysic are of the overarching “formal/rational” category Moral Philosophy, as we are talking about a more idealist sort of philosophical knowledge about ourselves and the universe (like how we should act and what morals our action should be based on).

Here we can say that things that can be confirmed empirically, and that are of natural philosophy, have the most definite and binary nature.

Sure, yes, the nature of the universe is probabilistic (that is empirically true), but the laws of physics are definite, empirically provable, and follow specific laws of probability.

Meanwhile, metaphysics and ethics and the social sciences and all else that comes from within to some extent produce a sort of probable truth (despite any definite qualities it might have).

In other words,

- Externally and definitively provable human knowledge is: Material Physics and the aspects of the related logic which explain physics and that which arises from outside of us; so the non-metaphysical aspects of natural philosophy.

- Internal and probable human knowledge that can’t be confirmed empirically with certainty (and must be confirmed at least in part internally) is: Formal Ethics and Metaphysics and theoretical logic which explains that which does not arise from the outside world and that which is not physics; so the metaphysical aspects of logic, ethics, and metaphysics.

With all of that in mind, we can consider each category to have a material aspect and a “pure” formal aspect (so in the physical we have pure empiricism AKA the theory behind science, and practical natural lab science AKA the actual physical acts related to science).

In other words, by pairing the concept of the categories with the concept of the material and formal, and defining everything that arises, we get a few different ways to relate everything and invoke the terms empirical, material, rational, and formal.

And with that in mind, deducing things further with the same logic, what we are really saying is that we can have:

A physics, logic, ethics, and metaphysics of… physics, logic, ethics, and metaphysics!

To avoid confusion, on a table (without the formal and informal subdivisions of the four primary categories illustrated), it looks like this:

| Spheres | Empirical (Material sphere of facts based on experience) | Rational (Formal sphere of facts about ideas) |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Philosophy (Material sphere of facts based on experience) | Physics (Empiricism) | Logic (Pure Reason) |

| Moral Philosophy (Formal sphere of facts about ideas) | Ethics (Philosophy-in-Action) | Metaphysics (Pure Philosophy) |

Now, the same table again, but this time with additional material and formal divisions:

| Spheres | Empirical (Material sphere of facts based on experience) | Rational (Formal sphere of facts about ideas) |

|---|---|---|

| Material Natural Philosophy | Material Physics (Practical Material Empiricism) the Physics of Physics | Material Logic (Practical Material Logic) the Physics of Logic |

| Formal Natural Philosophy | Formal Physics (Pure Formal Empiricism) the Logic of Physics | Formal Logic (Pure Formal Reason) the Logic of Logic |

| Material Moral Philosophy | Material Ethics (Practical Philosophy-in-Action) the Physics of Ethics | Material Metaphysics (Practical Material Philosophy) the Physics of Metaphysics |

| Formal Moral Philosophy | Formal Ethics (Pure Formal Philosophy-in-Theory) the Logic of Ethics | Formal Metaphysics (Pure Formal Philosophy) the Metaphysics of Metaphysics |

TIP: When we say “pure” it means formal, that which is “purely” rational (the world of ideas and internal things). When we say empirical it means material, that which is detectable with the senses (the world of facts about the experience of external things). Meanwhile, if something is “practical” then it is “actionable.” So practical physics is applied physics, while theoretical physics is “pure” and “formal.” These terms are sometimes used in different ways, but I’m trying to use consistent terms used by Kant here.

The Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics of The Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics (the Fundamental Transcendental Categories)

With the above models in mind, we can actually subdivide this again.

This last sub-division will unveil the true character of our model. That being, that we can abstract the formal and material to their logical conclusions to the result of having a Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics of Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics, where:

TIP: Each phrase below represents a category in which to place all human knowledge that belongs in that category, so each example is only some of the possible examples. Consider every subject one studies in school, and every field one enters into after, can be categorized below. Knowing this we will be able to see things such as “why aspects of the social sciences are elusive and uncertain, despite being useful and true,” and more. Consider, people are physical beings, and so are economies and markets, but the relations between those physical bodies are not purely material, and thus uncertainty is introduced (and thus truths become probable and not externally fully knowable).

NOTE: There is some serious overlap between categories here (which for me is a sign that this level is a good level to subdivide into). What is the difference between the physical aspects of metaphysics and the metaphysical aspect of the physical? Great question! I’ll answer that here and in the next notes (as i’m working on phrasing it and thinking on it). Part of me says one contains F=ma and the concept of beauty and the other contains force and a beautiful object. The other part of me says, these categories as simply [in Kant’s terms] transcendental and bleed into each other to such a degree that we should treat the physics of metaphysics and the metaphysics of physics as being of the same transcendental category. I assume this will become clear over time, for now, each of the 12 gets its own definition, but can none-the-less be considered transcendental in the cases where we get a mixed category (like the metaphysics of physics) and pure when we get a pure (in the sense of “only” not in the sense of “formal rationalized idea”) category (like the physics of physics).

NOTE: The categories below should explain themselves with a little critical thinking. The physics of physics should be thought of as “the physical aspects of physical things.” Likewise, the ethics of physics is “action as it relates to physical things.” So the physical aspects of metaphysical ideas (sentiments and imagination) speak to real things like music, art, feelings as chemical reactions, and the metaphysical of physical things are more like the theory of physics, the theory of music, the theory of art (aesthetics). Both those cats are “of material natural philosophy and formal moral philosophy,” but they each express a different aspect of this relation. The way these categories bleed into each other is “transcendental.” See “the spheres of human understanding” for more on that.

NOTE: These categories represent different “flavors.” Some flavors are pure (like the physical aspects of the physical; “the physical”) and some flavors are mixed (like the metaphysics of the physical). Mixed categories represent where transcendental knowledge and be categorized. The transcendental aesthetic, that is in the metaphysics of physics (and bleeds over into the physics of metaphysics). A synthetic a priori, that falls in the same category (it speaks to both the physics of metaphysics and the metaphysics of physics). Lastly, geometry, music, and color all have both physical and metaphysical qualities, aspects of them are, therefore “transcendental.”

NOTE: This section still needs work, take it as an example (not as gospel, when it is refined to the point of being near gospel, the note will be removed).

- The Physics of Physics (material physics) describes that which is (like a rock); the purely external that can be experienced directly (or via measurement tools). All action that does not involve free will is this. Literally physics and also “being” in general. If it is a material object in reality, it is in this category. If it is an effect of a thing or an idea, it is not of this category. In reality, most things arise from this fundamental category.

- The Logic of Physics (pure logical physics) describes the logic of that which is (like F=ma, the logic of how a rock falls on earth); describes the logical aspects of theoretical physics (the mechanics of physics). The logical systems behind the physical world.

- The Ethics of Physics (ethical material physics) describes the art of correct experiment and measurement (for example the art of employing the scientific method); also the social sciences touch upon this category. Also could describe things like how to treat the earth, or perhaps even how a positive and negative charge attract. Anything that has to do with action (sentient or not) and the physical world is of this category.

- The Metaphysics of Physics (pure metaphysical physics) describes aspects of theoretical physics; and the art of appreciating beauty and earthly pleasures (aesthetics); our emotions arise from here (on a chemical level). So, everything from music and color theory to theoretical physics (everything that speaks to the metaphysic aspects of the physical realm).

- The Physics of Logic describes the literal equations we use (how formulas work).

- The Logic of Logic describes the formal logic behind the equations.

- The Ethics of Logic, the best ways and best practices of using logical rule-sets (from math to rhetoric and reason).

- The Metaphysics of Logic, from theoretical mathematics to theories like Gödel’s, to theories of influence, rhetoric, and reason.

- The Physics of Ethics, practical ethics in action (the action).

- The Logic of Ethics, the logic behind the action.

- The Ethics of Ethics, manners and such (considerations on the action).

- The Metaphysics of Ethics, the moral and theoretical considerations of ethical rule-sets.

- The Physics of Metaphysics, morals in action, practical philosophy, emotional reactions (that which one can experience even if they can’t define or measure); the Church is a thing of physics and metaphysics.

- The Logic of Metaphysics, epistemology, the logic behind theorizing on what we can’t know for sure and that which we can.

- The Ethics of Metaphysics, considerations for actions based on morals.

- The Metaphysics of metaphysics, the study of that which we know we cannot know in any other way except internally; includes pure theology.

| Spheres | Material Natural Philosophy | Formal Natural Philosophy | Material Moral Philosophy | Formal Moral Philosophy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material Natural Philosophy | The Physics of Physics | The Physics of Logic | The Physics of Ethics | The Physics of Metaphysics |

| Formal Natural Philosophy | The Logic of Physics | The Logic of Logic | The Logic of Ethics | The Logic of Metaphysics |

| Material Moral Philosophy | The Ethics of Physics | The Ethics of Logic | The Ethics of Ethics | The Ethics of Metaphysics |

| Formal Moral Philosophy | The Metaphysics of Physics | The Metaphysics of Logic | The Metaphysics of Ethics | The Metaphysics of Metaphysics |

TIP: At this point, we could start classifying things in each category or could get meta and discuss the physics, of logic, of metaphysics, of ethics (etc) or things that belong in three or more categories (etc). Want to classify the animal kingdom? That is a logical system of the category of physics. Want to categorize the behavior and treatment of animals? That starts to dip into ethics. Want to categorize the law? That is a logical system of ethics. Etc. We aren’t going to get meta on this page and classify the arts and sciences and genre of every possible thing… all we want to do here is establish a basic system for categorizing epistemological knowledge. We don’t need or want to try to present a complete explanation of our current customs for categorizing every object on earth. Let us just say, math generally goes in the logic category, geology in the physics, geometry is a mix, theoretical physics is a mix of everything but ethics, and politics in its true and broadest form contains aspects of all four categories.

TIP: Below are four videos. One gives a “map of philosophy,” one a “map of the maths,” one a “map of chemistry,” and one a “map of physics.” All philosophy is essentially “of the metaphysics” to some extent, but regardless we can take each category from the philosophy below and place it under our categories above. Does it deal with ethics and action? Well then it goes in a category with the term “ethics in it.” Does it deal with the foundational logic of metaphysics? Well that is a sign it goes in the logic category (generally under the metaphysics of logic or the logic of metaphysics). Likewise, we can do the same for the other videos. Are we discussing chemistry? Well chemistry is a physical system, so it will go in cats that have the word physics in them, the ethics of physics perhaps (which is the category of physics that deals with action… and what is chemistry if not physical non-sentient things in action?). Are we discussing physics? Most of that will be covered under non-sentient action and the physical category itself, but of course, there are lots of metaphysical aspects of that. Lastly, for the maths, while they are all rooted in logic, they also often relate to metaphysics. After-all theoretical physics is a thing of logic, but also of metaphysics and physics. Sure, the basics like a number itself are purely arational (but don’t they also speak to the physical act of counting?) If we consider theoretical math, it is metaphysic. When we consider change there are aspects of physical and non-sentient action going on. Yes, these categories transcend, and we’ll need to consider mixed categories, but this is why we use transcendental categories for the complex things that arise from the simple dualities. With that all in mind, we can take the systems in the videos below and place each category or subject or sub-set and place it neatly into our categories above. If we couldn’t, then this wouldn’t be a very good “system of fundamental categories of being and knowledge.”

The Map Of Philosophy. A basic overview of the branches, see our more complete list below. Notice the colors they use in their map. Yellow for logic, green for the physical, blue for metaphysics… these colors are consistent with western element theory and astrology. Are they convention or not? We won’t muse on that question of metaphysics, but let us just say, I know I did not pick them at random for our theory. The colors like the subjects have meaning. All philosophy is the art science of moving toward knowing and exploring that meaning. The Map of Mathematics. Plato tells us to start with mathematics. One of the many smart things he suggested. Math is a very simple analogy for all real systems. If we can categorize math into the applied/empirical and pure/rational we are well on our way to connecting all the dots… and we can, and this video does, and this page connects those dots. No, I don’t yet have a master list of everything categorized, but if you understand this system you can nonetheless categorize everything (as I will do when I’m fully ready). The Map of Chemistry. Arguments for a virtual simulation aside, while we can argue philosophy and math, it is hard for any empirically minded person to argue against chemistry. It is about as real as it gets… and guess what? The fact that it is the real basis of everything means that fitting it into our categories is very easy and symbolic of what we are doing with other fields to create a full list. A protein is real, made of real elements and real chemical re-ACTIONS, meanwhile, the logic behind it is logical, and the application can be considered, and the metaphysics of it, etc. All systems, real and theoretical can be placed in the categories. Now, is this useful? Well, that is a whole other question. The Map of Physics. If we can map out chemistry, then of course we can map out physics in a similar way. Both are physical systems in action that form the foundation of being.KNOWING VS. UNDERSTANDING: The top left category (physics of physics) is the most knowable with the senses (it is experienced), the bottom right (the metaphysics of metaphysics) is that which can only be understood from within using logic and internal feeling (our internal senses-that-aren’t-senses so to speak). The more we move away from each term and toward the other, the more knowable or unknowable the “human understanding” becomes! In other words, we can have understanding about the metaphysics of metaphysics, or whims, or fancies, or feelings, but we can’t “know for sure” in the same way we can about a rock or the laws of physics. To say this another way, notice how, especially if we consider the sub-divisions of formal and material and sub-divisions of physics, logical, ethics, and metaphysics, that there is a part of metaphysics that is formal in every respect (“pure” philosophy; the metaphysics of metaphysics), and likewise that there is a part of physics that is material in every respect (practical material empirical physics; the physics of physics). That lines-up well with the certainty with which most of us would feel we could know about each type of information. A rock is easy to know empirically, but how exactly do we approach knowing moral concepts empirically? Or conversely, how can we know a rock internally? Well, the answer is we use the model above to see where we can cross forks and know probable truths by pulling out all forms of application, experiment, and theory we can shake a stick at! Sure, we can hardly know pure philosophy with certain external empirical positivism, but that which arises from within is no less important (just more uncertain and internal). I’m not suggesting we publish statistics on morals in Nature (the peer-reviewed journal), but outside of the NATURAL sciences, we should care about this stuff. We want to eat all of our cake, not just the material parts, so to speak. From this lens, we really do have a duty (a metaphysical concept) to dig toward the metaphysics of metaphysics. For more, see Kant’s Groundwork (see link above).

What we can know by knowing what category an object or idea is in: The physical, logical, ethical (metaphysics as it relates to human action or conduct), and metaphysical are all classes that contain different types of knowledge. As such, “what we can know” about things in each category differs by category. The same is generally true for the related categories of moral philosophy and natural (and the sub-categories noted on this page). The physical includes what we can know with things like physics and observation (where things have probability in the way quantum objects do and have observable objective certainty), the logical with things like mathematics and logic (where proofs are objective, but logic is none-the-less a thing of pure ideas), the ethical with things like social science and experience (where we get a mix of the problems and perks of each other category), and the metaphysical with things like individual experience and imagination (where we can have useful knowledge, but deal with unknowns like we do in induction; where everything is at best probable). Information about the physical world possesses some aspects of certainty and can have logic applied to it (what makes the science of physics possible), meanwhile, metaphysics dabbles in the probabilistic and uncertain. All this to say, knowing which of the transcendental and categorical “primary” classes information is in, tells us about what type of knowledge we can expect to be gained from studying the properties of objects in that class. It also gives us information about how objects and ideas in different classes relate. And then, of course, the same is generally true for any type of category of epistemology, such as the one’s of Aristotle and Kant.

TIP: “I think therefore I am,” and one might say “I feel therefore I am.” Our thoughts and feelings are subjectively real to us and we can be very certain about them. Meanwhile, the rock in front of us is objectively real. Sure, our external senses could be tricking us, but so could our internal ones. All types of knowledge are useful, but each type has a different quality! Alone each type only paints part of a picture, the full canon of human knowledge, experience, and understanding can only be gleaned by crossing the categories.

Introducing Complex Relations, Sub-Categories, and Other Types of “Spheres”

From here can then move on to consider sub-categories and the relations between the categories noted above.

When we consider categories, sub-categories, properties of those categories, and their relations we are considering “a system,” for our purposes, we’ll call any system based on the above “a sphere.”

For example, we can consider the logic of physics in terms of economy (the logic behind the division of labor and resource and capital), and then we can consider the ethics of that, and upon what morals those ethics are based. We can, in words, consider logic, physics, ethics, and morals in “the economic sphere.”

We can also apply this line of thinking to other even more complex matters.

For example, we can consider “the relation of the concepts of left-wing and right-wing” in “the economic sphere” (so we can consider the physics, logic, and ethics of economy, abstracting concepts to define left-wing and right-wing positions in terms of economics, noting how specific positions relate to each other, to better understand the properties being discussed; more on that in the notes below; see the political left-right as an example).

By doing this we can ensure we know what type of information we are discussing, whether it is going to material or formal, and whether we are going to be discussing aspects of natural or moral philosophy as a primary or secondary factor (if at all). This will help us to understand what sort of knowledge we are dealing with in any discussion (and will help us to avoid senseless arguments that lack direction).

Great, so all knowledge should be able to fit in that sort of model, and thus it should work as a general metaphor for all walks of life, especially the social sciences and philosophies where things get a little ethereal (but where categorization and models are needed none-the-less to formulate things like ethical and moral principles and analyze things like laws).

Well of course, it isn’t that simple, but indeed, this is the gist.

TIP: When on the site I say “in the political sphere” or “in the social sphere” or “in the economic sphere”, I mean “in that sub-category and thus related to specific fundamental categories.” By knowing what categories we are talking about, we can better understand the relations between the properties of those categories. The concept of equity, for example, does not have the same implications in the economic sphere as it does in the social sphere, as the social sphere tends to be more rooted in the formal and the economic in the material, thus the distinction and the ability to denote the different “spheres” and their relations is important.

TIP: The spheres/categories can “touch” and relate, but they are always unique. If they weren’t, they wouldn’t be their own spheres. When we say pure physics, or pure logic, or pure ethics, or pure metaphysics, we are denoting a purely formal (non-physical) part of the sphere which never touches the other spheres. When we “cross forks” (when we find where categories relate and intersect or find the place where the material and formal of each category intersect), we are seeing at least “the shadows of one sphere” (or one part of a sphere) on the other. By tracing lines between the shadows, we can approach having knowledge of things. Ex. we can know F=ma, which is pure reason, but we can apply it to material physics (for example, we can apply our logical theory to building a bridge). Thus, in this we can show that a concept of pure reason (in this case F=ma) is empirically true (in doing this we have “crossed forks”); See also Plato’s theory of forms and Allegory of the Cave.

Notes on Categorization, Semantics, and the Nature of Metaphysics

Below we have taken this basic concept presented above, added some details, and then addressed a few “metaphysical” questions.

The primary goal won’t be to list every aspect of the categories noted or to prove we can have certain knowledge of metaphysics (the most prickly concept here, as it has been long known), rather it will be to offer additional insight to those who are still confused or want to further explore the different spheres and their relations.

First here are some notes that relate to the above, make sure to note the other types of categories defined by figures like Aristotle, Kant, and Mill (or see Hume’s Fork, as that theory illustrates the relations of ideas in specific categories well).

Just FYI I go in a different direction than Aristotle, Kant, and Mill. When they categorize they focus on that which is contained in Mill’s a System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive. I meanwhile take the direction already noted (inspired more by Kant and Western Astrology and other aspects of Greek theory) and then pair that with Aristotle’s Golden Mean Theory and Hegel’s Dialectic. Then the other aspects of categorization would then pair with that.

In other words, there are different directions to go here, categorizing is a thing of pure thought to help us understand the world.

“We use the words Theological [theological metaphysics], Metaphysical [non-theological metaphysics], and Positive [empirically provable natural philosophy and its properties and relations], because they are chosen by M. Comte as a vehicle for M. Comte’s ideas.

Any philosopher whose thoughts another person undertakes to set forth, has a right to require that it should be done by means of his own nomenclature.”

-Mill’s August Comte and Positivism explaining that we can use different terms for categories and understand them in different ways. I use Kant’s system inspired by the Greeks for a model, Mill comments on Comte’s empirical theory of categorization at the base of his “positivism” which is reminiscent of Kierkengaard’s “spheres” from his Either/Or.

Mixed Systems, Other Types of Spheres, and their Relations: Many real systems are mixed. Economy is physical and logical, religion in action (not just spirituality, but preaching and praying in a collective in a church) is physical and moral, pure energy is arguably the ethics of physics (it is the physical in a state of action), and the appreciation of art (aesthetics) has a real metaphysical quality (in terms of the deep moral emotion it makes us feel). Here we aren’t just considering the four spheres on their own, each can and often must mix with the others. This creates sub-categories or simply other spheres for example the economic sphere (where we can consider the four categories “in the economic sphere”). Furthermore, we can and must consider abstractions of concepts (both in spheres and between different spheres). We can use these terms to describe most anything, and knowing they can have complex mixes helps to understand the logic behind that. In other words, the key to deep understanding is “the crossing of forks” between categories, in this way we can imitate the scientific process (which uses physics and logic) with ethics and metaphysics (to approximate ethical and moral laws for example). In words, we can create “analogies of experience” and figure out what is possible, actual, and necessary in terms of ethics and metaphysics based on what we know about physics and logic (we can apply Kant’s theory of knowledge to approach knowing things about ethics and metaphysics). TIP: Broadly speaking, we can mix each of the four main categories in any way, consider “sub-spheres” (like the economic sphere), and consider relations between properties in spheres and across spheres. I’ll do a page of examples of exactly what I mean here, but this is the general concept.

“Categories of the Faculty of Understanding“: Kant goes beyond just giving us four basic categories in which to place knowledge, he also considers how we can know things about each category (as do others like Aristotle, see Aristotle’s Categories and Kant’s Categories). The simplest example is the scientific method above, which pings physics against logic to come up with solid theories, but this is only one aspect. We can also consider things like the analytic and synthetic, and the necessary and contingent (these refer to the relations between categories/spheres). One can see our page on Hume’s fork to get an idea of how this works, or honestly, they can check out the Wikipedia page on Kant. Kant was operating at a high level and his work is a little difficult to get through, so while he is the master in this field, I suggest getting the simple version first.

Modes of persuasion: For an example of mixing the spheres, rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It uses a mix of ethos, pathos, and logos to sway people politically. Ethos appeals to the ethical, logos to the logical, and pathos, to the moral and emotional (it exploits political emotion so to speak).

IS MORAL PHILOSOPHY REAL? It is reasonable to say that, as far as we know, all things arise from the physical world (that the positive and empirical view is generally correct). A “form,” from Plato’s theory of the forms (not unrelated to the concept of “formal”), isn’t a real thing that exists before the physical. Instead logic, ethics, and metaphysics can be said to arise from the physical to take on their own unique properties. I truly believe that people misunderstand Plato and that he was clearly speaking in metaphor when he spoke of arete and essence and forms. Thus, for this theory, we may treat a “form” as true, but necessarily dependent on physics (in that it relies on being confirmed by us internally, and we are of course physical beings made of star stuff, which is magical enough on its own without turning to speculation). With that in mind, I’m not looking to prove the validity of logic, ethics, and metaphysics here, nor am I trying to prove whether the chicken or egg came first with certainty, nor am I claiming that knowledge of metaphysics is more useful than positive empirical knowledge, I’m only pointing out that we can have knowledge about things that aren’t purely material (and then, as a secondary point, insinuating that that knowledge of the world of ideas can in fact be very useful in its own way).

A justification for considering metaphysics: The reality is, that our forefathers from the Greeks to the Enlightenment thinkers have already worked out how to explain the world with only physics, logic, ethics. Meanwhile, in the west, we explain everything with physics and logic. Still, I think it is important that we not forget metaphysics, despite its frustrations (less we all “unbalance the scales”). We don’t ignore dark matter just because we can’t prove it, we don’t ignore quantum physics just because it is ruled by odd probabilistic laws, why ignore metaphysics? Does something have to be confirmable with the senses to be useful? In some fields, certainly, in others, I personally think it is folly to forget metaphysics. Once you trudge through some more information, I’ll introduce you to the idea that our forgetting of ethics (to some degree) and metaphysics (specifically morals) in the modern west has not been a fully “good” thing.

TIP: Where we can’t have certainty, for example in the ethical and metaphysics spheres, we can approximate and use analogies (we can admire the shadows on the cave wall and create reasonable theories). We don’t have to know something for 100% certain to have useful knowledge that works… that is sort of what the whole scientific method is about. So, for example, if 9 out of 10 people in the world hold a strong moral belief of a sort, we can consider that to have weight. Ideally, we can “cross forks” back to the empirical, but even when we can’t, we can have a sort of fuzzy knowledge about intangible things like “what is justice?” Does it really matter if justice arises from the human experience and doesn’t float around as a form in the sky? Would it change the idea that justice is important if we confirmed it was just some chemical trick?

A Description of the Spheres of Knowledge and Some Core Principles of Human Understanding

With the logic out of the way and the basics of the full theory noted, in an effort to ensure the above makes sense, let’s review the basics of the above theory again with some extra details.

Each of the spheres of human understanding AKA Spheres of knowledge, or categories, etc (which from here forth we’ll simply call physics, logic, ethics, and metaphysics) is unique (if it wasn’t, it wouldn’t be a different “sphere”).

The empirical is easiest to confirm (as we sense it directly). This is the preferred knowledge type and the core of most knowledge from Lockean principles to those of the Scientific Method.

Next comes logic, things like F=ma or 1+1=2. Those facts aren’t as tangible (if they were they would be empirical), but they are confirmable. We constantly use reason, symbols, and other logic in practice, so we can feel pretty comfortable with this one.

The simplest example of proving logic is a type of knowledge is that F=ma is not empirical, but rather pure reason, yet any engineer can confirm this Newtonian principle with perfect accuracy with every structure they build. We can know force equals mass times acceleration indirectly via empirical data and testing… even though we can’t know it directly. In this same way, we can also know facts about ethics and metaphysics.

The ethical is harder to define, but we can see it in the way lawyers act, or the way a soldier adheres to a code of honor, or to the way a King leads the charge into battle. To the extent that we have “ethical knowledge” (such as that contained in the Constitution), we can confirm this is a sphere of understanding (more on this later).

Lastly, the most ethereal, the metaphysical is the hardest to confirm knowledge of. It is the equivalent to trying to define empty space. What is it that drives our ethics? Is it logic or the purely physical? Can we confirm knowledge about morality empirically, or is this one sphere always going to remain ethereal? Those are all good questions.

We can seek to prove that we can have useful facts about of the types of knowledge by finding the places where the realms of knowledge “cross forks“, like we did with logic and empirical data with F=ma, and this will theoretically allow us to confirm aspects of the more elusive non-empirical ethics and metaphysics… but that subject is secondary to this introduction (especially given the history of moral philosophy, which shows us these questions are still generally unanswered and to what degree they are answered the answer is “we can’t prove facts about pure philosophy”).[3][4]

Understanding the Spheres of Human Understanding: Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics – More Details

Synthesizing all the above, we can say these terms can reasonably be placed into the model we offered above.

| Spheres | Empirical (Material sphere of facts based on experience) | Rational (Formal sphere of facts about ideas) |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Philosophy (sphere of facts based on experience) | Physics (Empiricism) | Logic (Pure Reason) |

| Moral Philosophy (sphere of facts about ideas) | Ethics (Philosophy-in-Action) | Metaphysics (Pure Philosophy) |

And for more detail, the categories (0r spheres) can be described like this:

- Physics: Is that which is. It is detectable with the senses (or theoretically with measuring technologies). The study of the purely physical was once called natural philosophy and now is called “the natural sciences” (i.e. not only Einstein‘s physics but natural science; the knowledge of all things physical).

- Logic: That which is, but is a thing of pure reason (it describes “what is”). It is not directly detectable by the senses, but it correlates perfectly with the physical. F=ma is pure logic, but it is also a simple equation that explains local gravity. 1+1=2, if it didn’t, computers wouldn’t work. These are logical rules that govern the physics. It is what we call theoretical science and mathematics, it is the logic of the physical.

- Ethics: Is that which ought to be, applied to the physical (like when a judge or lawyer acts upon the law). It is what separates a human from a reptile(? – something that acts only on impulse, instinct, or preprogrammed action in other words). It is free will, it is action. It is what we call ethics and law. All the practical moral sciences.

- Metaphysics: Is that which ought to be, but is a thing of pure philosophy (it describes not “what is”, but what is behind that, the true nature of things). There is a reason the Greeks didn’t define this term, it is ethereal. But as Kant implies in his Foundation of the Metaphysics of Morals, this pure philosophy is important in the same way pure reason is important. Where pure reason tells us about physics, metaphysics tells us about ethics.

An example of the difference between ideas and experience: “All bachelors are unmarried” (idea) vs. “A bachelor is sitting in the chair” (experience). We know the bachelor is in the chair because we see him sitting there. We only know all bachelors are married because they are bachelors (we can’t go around confirming each of the world’s bachelors is unmarried via our senses). We know this logically because it is necessary for the sentence to be true, but it tells us nothing specific about our world (it is a fact about an idea, not a fact about the world). It is redundant, what Hume calls a tautology. We don’t want to look for tautological proofs to prove facts about ideas, we want to look for testable Synthetic a priori: facts about ideas that are true even though we can’t confirm them directly. This is to say we want to 1. look for “Synthetic a priori” that we can 2. test and prove through indirect empirical evidence.

TIP: Note that “logically” one can make a case that we can’t confirm facts about pure philosophy empirically (even if we can have a metaphysical “Synthetic a priori”, we can’t prove it). This is the stance Kant takes, he doesn’t think we can create a discipline out of the metaphysical “Synthetic a priori” knowledge because it can’t be tested empirically, but he does believe that we can know facts about pure philosophy. I tend to think there should be some theoretical way to indirectly prove metaphysical “Synthetic a priori” knowledge (by crossing forks with ethics, logic, and physics)… but that is probably out of scope for this article.

Ex. We can empirically and logically show that the non-aggression principle is true, and from this, we can construct ethical laws from the natural laws of self-defense. However, one can’t prove empirically with certainty that “killing in self-defense is correct”. Likewise, we can say that which does the greatest good for the most people and the least harm (utilitarianism) is grounded enough in reason to create an ethical-moral first principle… but we can’t make the leap to saying, it is a fact: “the meaning of life is happiness“. These “moral” statements of pure philosophy aren’t so easily proven, but physics, logic, and ethics are enough to hold them up in court and the social contract (they are good and useful facts, but not empirically provable with certainty). We can use the concept of “fairness” liberally, but we can’t confirm it exactly. Still, we can argue that “knowledge of justice” is a useful “knowledge of pure philosophy”. Pure philosophy can contain “Synthetic a priori” (so to speak), but not empirically provable principles and propositions.

Shouldn’t metaphysics and physics be in the same category as logic and ethics? One would think that the relationships between these four should be that physics is the “what is” of facts and metaphysics “the what is” of ideas, and then ethics and logic are the intellectual (non-physical) aspects of these. But the relationship between the four isn’t a duality, it is a quadrality in balance. So Physics is what is, logic is what we know, ethics is action, and metaphysics is what we can know about the morality of that action. I’m very certain the above is the correct way to display things. That said, these are all terms created by Humans, the core of what they explain is more important than the names.

TIP: Kierkegaard’s three spheres (or “three stages of life”) are related to this theory. He categorizes human experiences regarding happiness as aesthetic, ethical, and religious. To equate that to this theory, physical pleasures are aesthetic, logical and ethical pleasures are ethical, and metaphysical pleasures are religious. See theories on happiness as the meaning of life.

TIP: Other aspects of this theory are worked out on our page on our “Western Classical Element Theory as a Metaphor” and our“Separation of Powers Metaphor”. See those pages as well. At some point, i’ll attempt to combine all this, for now, the theory spans several pages.

An infographic displaying a model for the separations of power (a related metaphor).

Understanding Kant, Hume, and Others Via the Above Theory

In the above chart, we can understand why Hume says physical material empirical data that we can know with our senses is the only real truth.

Physics is the most factual, it is the only one that exists purely in the sphere of empirically confirmable facts (the physical world).

Likewise, we can understand why Hume assumed that pure logic could not tell us about the world.

We can also see why Kant was able to cross Hume’s fork and show that logic could tell us about the world (where F=ma most certainly tells us about the world even though we can’t touch it). Sure, we can call that pure logic that relates to physics “pure physics,” and denote it as the formal aspect of the physical, but that categorization method aside, it is most certainly pure reason being applied to the physical.

Those points of natural philosophy are easy to get once you get the hang of it, it is having that same discussion about ethics and metaphysics that gets tricky (although both Kant and Hume attempt, rather successfully, to do this… they do not come away with as rock-solid answers as they do with physics and logic).

Here we can see that, theoretically and logically, what is true for physics and logic should be true for ethics and morals by some measures and impossible by others.

Morals should be able to tell us about ethics. That is, we should be able to construct “correct” ethical laws from moral metaphysics (rationally, given what we can do with physics and logic).

However, I think it is a bit more complicated. I think we need physics and logic as a foundation, and then from that point, we can pair ethics and metaphysics to tell us facts about the world (and indeed, this is essentially what thinkers like Locke and Mill do when laying down their moral and ethical principles).

When we act with ethics, we affect the physical, AND we can use logic to create ethical laws based on physical results (as anyone with a law degree knows).

We can from just physics, logic, and ethics create laws like the non-aggression principle and utilitarianism, creating first principles of morality without ever discussing metaphysics!

That is a neat parlor trick, for sure, and [as Hume eludes] it is infinitely useful for conveying moral ideas to non-philosophers… but it also implies that we can’t have knowledge about pure philosophy, and I don’t think that is correct and neither did Kant to some degree (Kant doubts we can have empirical knowledge of formal “pure” philosophy; but obviously thought we could know about it, hence writing volumes on the matter).

So how can we know something about something that we can’t know directly? In some respects it is, in the same way, we can know facts about logic even though we can’t hold a logic in our hands.

The spheres intersect and react with each other (speaking metaphorically). So we wouldn’t be looking for facts about metaphysics in metaphysics, we would be looking to see the shadows dancing on the physical wall, we would be looking for the intersection to see where the forks cross.

A sphere by its definition is its own thing. If it was not partly its own thing, then it would not be a different sphere.

However, if the spheres did not intersect in any way, then there would be no pathway between them.

If pure metaphysic philosophical morals could tell us nothing about ethics, then our ethics would be based only on physics and logic.

But wait in this lies the answer, if the empirical and natural is a reflection of the moral in any way, then as any good empiricist like Locke or Hume knows, we have a workaround without ever having to get refer to Aquinas and his Divine laws.

We simply say, “that which is physics,” tells us about the ethical laws using reason (using logic).

Still, from this, we can extrapolate, that that which we glean from the physical, logical, and ethical is a shadow of the metaphysic dancing on the cave wall. We know we can’t hold it in our hand directly, like an equation, so it shouldn’t be looked for in that way.

We may not be able to have testable certainty [more like probabilistic quantum quasi-certainty if anything] about “the metaphysics of morals”, but we can have good theories that work and we can have what we can generally call “facts about pure philosophy”. That is a little weaker than F=ma, but that is what one can expect from the purely incorporeal.

All around us sits empty space, it is there, it has properties, we can point to it with logic, but it is ethereal and uncertain. Metaphysics is like the empty space of human understanding. It is there, just hard to poke with a stick directly.

Finding all the places where the metaphysic fork does cross into other spheres is a tall order, but it gives us reason to state that:

All knowledge, all human understanding, can be placed in four groups: Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics… with each type having its own complexities in terms of proving absolutes about what exactly we know.

Where we can be the most certain about physics, and via that empirical data we can confirm our logic, through our logic and physics we can begin to confirm aspects of ethics and metaphysics.

There are some known-unknowns and unknown-unknowns here… but this is about categorizing knowledge, not knowing everything that is or ought to be (confirm dark matter and empty space; and if there is still no metaphysical moral certainty, at that point we can talk; even physics has an opposite but true force, just like many of the standard model particles and interactions).

There is plenty of physics we still don’t know, to assume we would know all of metaphysics given its much more ethereal nature is a little optimistic. Not knowing something proves nothing, not knowing is where the desire for understanding comes from, it is not a logical argument for the non-existence of a thing. If morals weren’t “a thing”, if the only things that were mattered, why do people act morally, go to church, or dedicate their lives to principles that go beyond what is purely physical, logical, or rational. What is empathy? What is faith? etc. Religion isn’t pure metaphysics, but its core of spirituality is in its sphere (and the church itself and its doctrine is that which takes the metaphysic and brings it into the physical realm, using the symbols of logic no less).

NOTE: Given the metaphysical sphere is the most elusive, and thus the hardest to talk about or pin down, we can see how it is the easiest to forget. Probably one of the biggest vices of our modern liberal capitalist Republics is the general moving away from metaphysics (morality, faith, spirituality… religion). Having freedom of religion is vital, but freedom from spirituality is a bit more troublesome. A modern political argument might consider the physical, the logical, and perhaps even the ethical (typically in that order; with sometimes “ethics” being based more on physics and logic than its moral side, with “law” being almost a synonym for “the will of the stronger faction“)… but rarely does it consider the moral first. When we discuss healthcare, it is about dollars and sense, not the morality of healing the sick for example (see these comments). This problem is not so easily solved, and perhaps it is better not to solve it than try to solve with too heavy a hand (i.e. Church states aren’t the answer, at least not one’s that push a very specific doctrine… as philosophy requires liberty, as Hume says in his essays on Human Understanding). Still, it is worth noting as it directly pertains to this subject. Liberty, equality, laws, rights, and morality are mutually dependent subjects, like the spheres of human understanding, different, complicated, but undeniably linked.

MUSING: When I hear [er um, read] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn say “Men have forgotten God”, I don’t take him to mean it literally (even if he did mean it literally), instead I believe it is best translated to “people have, in their satisfaction with our new way of life, forgotten the importance of the metaphysics of morals” or “people are too focused on the physical and logical natural philosophies, seeing even ethics through this lens, and they have thus forgotten the importance of metaphysics and moral philosophy.” If we don’t have a moral compass guiding our ethics, then it is physics and logic that guide our ethics… that at best gives us a technocratic set of morals, and that isn’t I think what Locke and Mill were getting at. To the extent, we can find morals using reason and empirical data, great, but we aren’t looking at physics and logic, we are looking at the shadows of the moral forms dancing on the cave wall. We all love us some Aristotle, but let’s not totally forget Plato (well, let’s forget the idea that we should take his noble lie literally, but let us not forget the intent behind his metaphors).