The Basics of a Theory of Knowledge

A Basic Theory of Human Knowledge:

A Theory of Human Knowledge and Understanding; A System of Concepts, Logic, Reasoning, Relations, and Categorization

We present a basic theory of human knowledge to help illustrate some essentials of “what we can know” and “how we can know it.”

An Introduction to Ontology and Epistemology

The study of what we can know is called “epistemology,” it is a branch of philosophy that deals with logic, reason, truths, arguments, categorization, and such. The whole ends of epistemology is to better understand what we can know using logic and reason.

To understand what we can know, we have to also consider the nature of being (and non-being and change) and the corresponding basic categories of being and their relations. The study of being is called “ontology.”

In other words, to have a theory of knowledge we have to trace reality, to our conception of reality, to our mental processing of reality and ideas, to the language we use to communicate and work with propositions, to the rule-sets we use to categorize and work with all of this. Thus, to practice epistemology we have to practice ontology.

In sum, epistemology and ontology are branches of philosophy which focus on “what we can know,” “how we can know it,” and “how we can categorize that knowledge.”

Thus, this page presents “a basic theory of epistemology (and to some extent ontology) that focuses on the logical categorization of concepts related to reality, human experience/understanding/knowledge, and their relations.”

A Summary of a Theory of Human Knowledge and Understanding

Although there are some clear fundamentals, there is no one way to start talking about human knowledge.

Given that I’ll simply list out some important concepts in roughly a chronological order to start. In terms of getting from point A to point B in the “what we can know” conversation, we want to consider:

- The concept of abstractions, contradictions, and dualities (from the 1 comes the 2, comes the range of middles between; from the thesis the antithesis, from those the synthesis).

- The concept of being, non-being, and change (to categorize what we can know, we must understand what is possible). Any epistemological system of logic must begin with an ontological system of categorization. To determine what we can know via human experience, we must consider reality in its totality first.

- What exactly human knowledge, understanding, and experience are, and how this leads to concepts/terms… and how reality, conception, thought, language, and communication relate when talking about ontological and epistemological truth.

- The foundation of logic and reason (terms/concepts, logic/judgements, and reason/inferences), and the related physical neurological systems of sensory (observation), short term (storage of a few things and “working with them”), and long term memory (storage of all things, the connections between them, and working with them).

- The fundamental dualities of empiricism (what we can sense) and rationalism (what we think), the related material (physical objects) and the formal (the non-physical), the related concepts of certainty and probability and objectivity and subjectivity (and the related flavors of probability), and the fundamental four categories or classes of physical (being), mental (thinking), ethical (action), and moral (feeling) that arise from this. I.e. to consider some categorical classes which properties, concepts, judgements, and arguments fall into.

- The different types of reasoning that can be used to work with reason and logic (inductive, deductive, and abductive and other complex types)…. and how different types of sensory experiences and rational ideas form the basis of properties, concepts, judgements, and arguments and how we can determine truth-values and probabilities based on this (by understanding the categorical properties of these things when working with them in propositions).

- The relations of terms and the anatomy of an argument (how terms like subject terms and predicates relate in propositions, and how propositions become premisses and conclusions).

- Classifications for types of concepts, judgements, and inferences and their relations.

- The argument forms like the syllogism, and some related aspects of thought like analysis (where we break a complex thing into parts) and synthesis (where we consider how parts connect as systems and how systems and parts relate).

- The nature of the types of truth and purveyors of information.

- And the models and theories we can create knowing all of this.

- And more.

The problem is therefore less about what to talk about and more about a logical order to place these interlaced and often equally important bits of information into.

With all that said, it makes sense to start back at the beginning and focus on the question “what is Human Knowledge,” and then to let things unfold from there as we reintroduce the basics we just noted above and categorize things along the way.

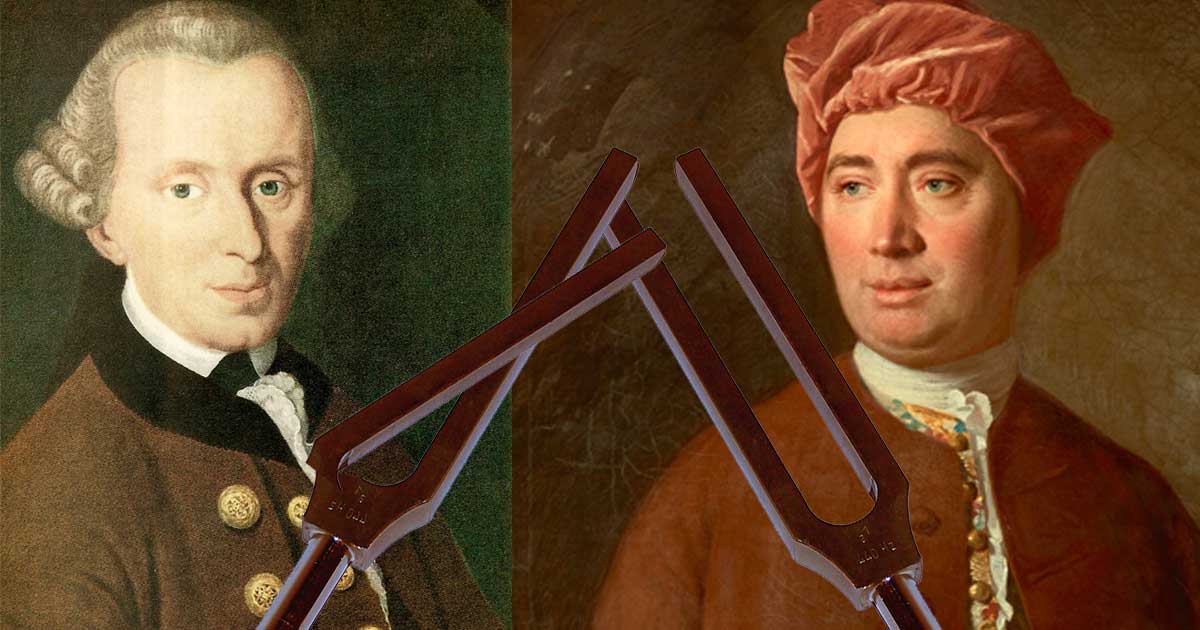

An Introduction to the Cannons of Epistemology and Ontology: The theory below (which is still in the works) is my own synthesis of past theories from philosophers like Hegel, Mill, Kant, Hume, Locke, Aristotle etc. You should not use this as a cheat sheet for a test, as part of the theory is unique (it is a synthesis of many theories, not an attempt to recant Kant purely).[1][2][3]

Reading: To supplement this see the works on logic, knowledge, understanding, and categories of all the aforementioned philosophers or crack open a 101 book on logic and reason. For Hume’s argument, see: Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding by David Hume and his Enquiry Concerning Morals. For a summary of Kant (who offers a rebuttal of sorts of Hume) see Understanding Kant for the super simple version, or for a full version see Kant’s theory of knowledge by Prichard, H. A. (Harold Arthur), or, if you are up for the challenge, see Kant’s own Critique of Pure Reason, and his Fundamental Principles [AKA Groundwork] of the Metaphysic of Morals (those are the two main works on which this theory is based, consider reading the first part of each). For Hegel and Locke, see their works on logic. For Mill, see his work on Comte and his System of Logic. This all relates back to conditional reasoning forms like Syllogisms and the concept of categorization by the Greeks, and generally to most epistemological theories of the great thinkers; So see also Aristotle’s Categories for some roots and see categories from the Stanford Encyclopedia. TIP: Also check out Deductive Logic by St. George William Joseph Stock, which I cite liberally on this page (it was laid out in a really… logical and simple way, plus it is free to read online).

Reality, Process, Product, and Language

If one wants to categorize everything (in an effort to figure out “what we can know” and “how we can know it”), they need to define what “everything” means. So let’s do that.

- The first level is reality: that is what is independent of human experience. This is the ontological study of reality.

- The next level is dependent on the human experience: 2.1 That is our ability to sense reality as it is (process), 2.2, our thoughts/conceptions about that (product), and 2.3 the language we use to discuss the product and process (language). This is essentially the epistemological study of terms and concepts as it relates to reality (where each term, real or imagined, is a set of properties, real or imagined). This category bridges the gap between what-is independent of our experience and all that the human mind can know theoretically.

- The next level is a study of the truth of the language as it pertains to the product, process, and reality: This is where epistemology and logic and reason come in (they, combined with ontology, study our first two points). This is essentially the epistemological study of logic and reason as it relates to all the aforementioned. This level contains human knowledge.

A given system may address parts of all three levels, or one level specifically, it depends on the purpose of the system. Our system will aim to categorize all these systems under one system. As, to understand human knowledge, we must account for the other systems.

NOTE: One could argue a base level of reality includes all that is, isn’t, and could be. It is all actual and potential. Only what is, is…. however, the absence of something and the potential of something are valid parts of reality on a very fundamental level.

What is Human Knowledge, Understanding, and Experience?

With the above said:

- Human knowledge is all that can be known (in any respect), either from direct human experience or from rationalization. Having knowledge.

- Human understanding is what can be understood (in any respect) by rationalizing based on what is known (the comparison, contrasting, and analyzing of things and ideas). Detecting Patterns.

- Likewise, human experience is everything we can experience directly with the senses or via rationalization and imagination. Perception.

For our theory, we will consider all “human knowledge, understanding, and experience” (everything below) as “human knowledge” (i.e. what we can know or understand, in any way, with any degree of certainty).

Simply put, from conceptualization, to rationalization, to imagination, to observation, anything we can process or store in our grey matter, for our purposes, it is human knowledge.

With that said, reality is not our perception of reality, reality is a larger system that includes our perception of it. Thus, we need to dip a toe into ontology to provide a basis for our epistemological theory of knowledge.

TIP: To consider all human knowledge we have to consider reality -> our perception of it -> how we understand it -> how we convey ideas to others and act. So a concept is a perception and rationalization of reality, then when we form that concept into a sentence that sentence and all its formal and informal meaning becomes human knowledge. If the subject of all this is “a rock,” we might use the words “concept” and “rock” to describe the reality of the rock, our perception of the rock, our rationalized ideas about the rock, or we might use “rock” in a sentence. This makes categorizing complex, but… but better to account for it as we move toward dealing with the truth behind propositions than ignoring it and being confusing.

An Introduction to Ontology Abstraction and Contradiction (the Nature of Reality)

Fundamentally there are three things to consider in the universe, they can be denoted in Plato’s terms as: 1. non-being, 2. being, and 3. the difference or change between non-being and being.

Here we aren’t trying to see this from a human perspective, we are just trying to denote the system of reality that humans are a part of.

Assuming this is true in general for reality, then this is true for all levels (as above so below as they say), including the one at the center of our conversation: mind/body duality. Thus, be we discussing the nature of reality or the subject term of a proposition, we are essentially always either discussing being (the material), non-being (the formal), or the in-between.

- Material reality/knowledge, which concerns some physical object (i.e. that which we can confirm directly via the senses or measurement; even if only theoretically), or

- Formal reality/knowledge, which is that which is not physical object (that which has no properties). In human experience it is that which pays no attention to differences between objects, and is concerned only with logic and reason (i.e. that which we can’t confirm directly with the senses or measurement; like an idea).

- The in-between, which concerns any mix of the above (anything from human action or entropy, which is change, to a physics equation or the concept of spacetime, which is rational knowledge that speaks to the real; this category includes both imagined ideas not grounded in reality and ideas grounding in reality about things like relations and non-being, time and space being examples… since this category is complex, we will subdivide below, but for now, it can be seen as the inevitable space between being and non-being in a world that isn’t static).

Simply, the nature of reality is that we are either talking about a thing (and its changes), a lack of a thing, an idea (related to things or not), or a mix (a concept which has both physical and metaphysical properties) when we talk about anything possible in the universe including that possible to the human experience or related to it.

Thus:

- Primary Category of reality: being-nonbeing-change.

- Primary Category distinction: 1. Non-Being, 2. Change, 3. Being

Thus, all our categories moving forward will relate to this fundamental category of ontology (this being one way to express a fundamental category; there is no one agreed on way, that caveat generally applies to the entire page).

By starting with the simplest classes of thing, we can then consider the endless complexity that arises (as it relates to ontology and epistemology and even more complex systems)…. and indeed, this is where Aristotle was going with his Categories, what mathematics shows us with fractals, and what physics shows us with quanta.

With that noted, to avoid getting overwhelmed with complexity, we can/should/will categorize the basics of human knowledge as they relate to this basic category of reality beyond human experience.

Moving on, let’s consider the basics of how we move from reality to our simple conceptualizations of it to complex thoughts.

TIP: There may be things in reality that we can’t or haven’t experienced or understood. These things are “reality,” but aren’t “human knowledge.” We can’t categorize or consider something no one has ever thought of. This means the study of being has some limitations that the study of “what we do know” does not. Thus, the main focus below will be a system based on what we do know and can potentially know; not a system based on a perfect system of reality as it is beyond our perception of it.

An Introduction to Conception (The Human Experience and its Relation to Reality)

To know something we must first conceptualize it, to conceptualize something we must be able to observe or imagine it. To observe or imagine something is to denote a set of properties (real or imagined).

The second we start observing reality we introduce rationalization, intuition, and conceptualization… and thus human knowledge contains that which is only loosely real (like imagined ideas).

With that in mind, we can call the simplest bits of information we can know (empirically or rationally) “properties” or “attributes” (like the physical property “green” or “big” or the metaphysical properties “happy” or “just”).

Then we can call any collection of properties a “concept” (which we can, and often do, call “a term”).

So what is a concept? It is simply a collection of attributes/properties.

What is a property? Physically it is quanta arranged in relation to each other, rationally it is the impression of a sensation or an idea (arising from physical stimulus of any sort or the imagination).

How can we know concepts and therefore terms? There are two generally ways (although both are informed by our external and internal senses):

- Intuition describes anything that can be understood immediately, without the need for conscious reasoning (whether it arises internally, like an emotion, or externally, like a rock).

- Conceptualization describes anything that requires some degree of rationalization (like a happy rock).

With that in mind, all concepts/terms can be placed in categories based on its properties, for cases where a term is part rational and part empirical, like a happy rock, we can place it in a mixed category (more on that below).

All terms can also be compared together, when we compare terms it is called “logic and reason.”

TIP: The theory that says everything is simply its properties is Hume’s “bundle theory.” This theory paired with our theory answers many of the arguments people have against bundle theory… but like any other concept on this page, it is theory and there is room for debate.

TIP: Humans can’t have new ideas without input. Speaking loosely, we can say “there are no new ideas” just copies, transformations, and combinations based on what we perceive from others, the world around us, or from our own transformations, combinations, and relations of ideas. We can imagine a happy rock, but we can’t imagine something completely beyond any experience, we rely on sensory input and analogy to reason. Anything we can imagine or sense, property, concept/term, judgements, complex idea, all of this is human knowledge. In this sense it is all rooted in reality (even pure imagination).

NOTE: When writing a logical sentence (a proposition) we can denote properties and concepts, saying “the cat is black” for example. However, if we want to know about more complex things we have compare concepts. Saying “the cat is an animal” is true, but it is tautological. Animal is a property of a cat. Since all concepts have properties, and since many concepts share properties, we can categorize concepts and properties based on their commonalities. The simplest category, the ontological one above, is “being,” “non-being,” or change. The cat is a substantive property (it is a thing that naturally has properties), “black” is not, it is a property.

TIP: In common language we can call much of what has been noted so far “concepts,” that is a problem of the english language, not the theory (this is why philosophers tend to coin new… terms). In logic and reason many oddities of language exist, don’t let it throw you off course.

An Introduction to Logic and Reason (Dealing With Reality as Concepts)

We can categorize all of human knowledge (specifically the processes and products of thought) into three categories, denoted as terms/concepts, logic and reason, where:

There are three processes of thought (what is happening when we think):

- Conception (any rationalized or observed/perceived conception of a thing)

- Judgement

- Inference

Corresponding to these three processes there are three products of thought (once we have thought we get):

- The Concept (any concept related to any of the categories).

- The Judgement.

- The Inference.

When the three products of thought are expressed in language (when we express our thoughts, they are):

- The Term (the actual words we use to describe things).

- The Proposition.

- The Inference.

Then this relates to the idea that:

- The concept is the result of comparing attributes (or properties; like greenness, roundness, etc; an object/concept/thing is essentially just a collection of properties).

- The judgement is the result of comparing concepts.

- The inference is the result of comparing judgements.

And likewise (to phrase the same thing in different words):

- The term is the result of comparing attributes.

- The proposition is the result of comparing terms.

- The inference is the result of comparing propositions.

In other words, there are three categories of logic which can generally be expressed as:

- Conception (the process form) -> Concept (the product form) -> Term (language form). This category can be expressed as Terms / Concepts. Terms or concepts are symbols that represent simple impressions or complex rationalizations that exist as subjects and predicates when used in statements. Ex. Socrates, men, or mortality.

- Judgement (the process form) -> Judgement (the product form) -> Proposition (language form). This category is Logic / Propositions. Logical judgements or propositions are statements about things and ideas that compare terms to seek understanding. Ex. Socrates (subject) is a man (predicate), and all men (subject) are mortal (predicate).

- Inference (the process form) -> Inference (the product form) -> Inference (the language form). This category is Reason / Conclusions / Inferences. Reasoned inferences are the determinations made from the pairing of many judgements and terms, and once a good theory is hashed out, it can be given a name (a symbol; a term). Ex. since Socrates is a man (judgement #1) and since all men are mortal (judgement #2), therefore Socrates is mortal (inference). Ex. 2. And now we can call this inference “Plato’s Syllogism,” now when we say “Plato’s syllogism” we know we are talking about this whole series of logic. This can be called “giving names to things.”

From here we can go in a number of directions, discussing every aspect of logic and reason, classifying things, and noting how the certainty of our inferences will depend on what type of information we are dealing with.

Then, eventually, the exercise of doing this will result will be an ability to tell truth, half-truths, opinions, theories, and other types of knowledge from each other… and will thus answer the questions, “what can we know and how can we know it?”

With that said, there are some other fundamentals we need to cover first. Namely, we need to think about what classes of concepts, statements, and inferences there are. This will give us a more complete foundation to move forward with.

TIP: Below we will cover “the categories” these are categories in which we can place all properties, concepts, judgements, and terms to get a sense of what ontological and epistemological properties they will have. Generally as humans we can’t fully trust our senses or our rationalism, thus there is a inductive nature to everything we know. Still, by following an ordered system of logic we can find very useful knowledge about things and determine truths to a high degree of certainty.

TIP: What we are dealing with here is generally analogous to the formal system of mathematics, where a small series of symbols can produce the whole of mathematics. There is really nothing more than a two-way split of empirical and rational and then the concept of pairing concepts and making judgements and drawing inferences and then coining new terms. Thus, human knowledge as a system is comparable to any simple system that gets complex quickly, such as the physical system of quantum physics, where there are only a few core properties, like a negative and positive charge, mass and energy, cause and effect, and where from the relations of these things the universe from that arises.

NOTE: If we say “happy rock” the subject “rock” informs us that the proposition is about a rock… and therefore we are either speaking in metaphor or being absurd or discussing imagination. If I say “the seat of the water is hard,” it is a hint i’m making a categorical mistake (that i’m trying to relate categories that don’t relate), or it is a hint that I’m using metaphor or being absurd or talking about fantasy. Context is very important when discussing logic… but when discussing human knowledge, we have to come to terms that we can know an absurd concept like “happy rock” in all its meanings and forms. Language is a formal (and informal) symbolic system, so when we speak in the language form (and stop denoting reality and logical systems) the subject of human knowledge gets very tricky to deal with in formal terms.

The Fundamental Dichotomy of Human Knowledge

The next step in our basic theory of human knowledge will be to discuss basic classes which we can categorize all properties, concepts, statements, and inferences under.

To do this we will consider the fundamental duality of “mind and body,” or rather of “rational and physical.” That is, what we can know through rationalization and what we can know through direct experience and observation!

All concepts (and therefore all logical statements and inferences) will at their core deal with either the rational, physical, or a mix.

Thus, while we can add infinite complexity, we will always simply be dealing with the core processes/products of thought and our “two pronged” class of rational and physical (and the mixes that arise from these fundamentals).

Likewise, we will always be able to relate all this back to the idea of abstraction, contradiction, and duality.

These aspects are the core of our physical experience as humans, and that is therefore they are necessarily the core of logic, reason, and epistemology. It isn’t any more complex than that at the core, however, from this simple rule-set, endless complexity arises (especially in terms of relations).

TIP: Here we are working with fundamental classes or categories. Like with logic and reason, a full discussion of “the categories” is going to go far beyond a few fundamental classes. The goal here is to start simple.

The Rational and Physical: Our Two Fundamental Classes

In general, although there is perhaps other ways to phrase this and other models to build, the following propositions are true:

- As we said above, human knowledge is everything that can be known for sure or understood or experienced to any degree (even if only theoretically).

- There are two ways to know things, via experience and/or thought.

- All knowledge that we can know directly via our senses is empirical, and all knowledge that we have to imagine is rational.

- When we know something about what we experience directly, we can call the truths that arise “facts based on experience,” when we know something based on thought, we can call what arises “facts based on ideas.” In science, we want to verify based on experiment to ground theories in “facts based on experience,” but that doesn’t mean that Pure Reason (pure ideas) isn’t useful (more on that below).

The following statements are also true and help add nuance to the above statements:

- All knowledge either originates from outside of us (ex. a rock, or even the words and actions of a stage play), or from within us (ex. an idea, our will, or a sense of Duty, our own feelings and thoughts, even those feelings and thoughts that are reactions to the words and actions of other people).

- All knowledge that originates within us either requires rationalization (like reflecting on the concept of duty) or doesn’t (like the reflex of pain). This experiences that come from within us leaves an impression, which we can know.

- All knowledge is either based on tangible and material things we can sense directly (ex. a rock or an action), or is based on something intangible and formal (AKA “pure“) that we can’t sense directly (ex. a thought, an imagined idea or moral, or the will to act).

Putting all the above together, we can say,

“All knowledge is therefore either knowable empirically via the senses (ex. seeing a dog, watching someone act out of emotion or Duty, or smelling a warm pie), “pure” formal knowledge that requires rationalization (ex. the concept of spacetime, ideas for dog training, mathematics, a moral theory, or theory of how to bake the perfect pie), or a mix (ex. the idea of a dog existing in spacetime, the applied science of baking, following a set of laws, a physic equation used to build a bridge, or practicing the moral code of a theological text).”

In other words,

- Of the empirical there are two kinds, those that exist in the physical world as things (a person, a rock), or those that exist as willful actions (such as the purposeful actions of humans).

- Of the formal there are two kinds, those that consider the natural world as it is (ex. empirical observations and pure cold logic and reasoning), and those that consider the world as it ought to be or those which consider that which we can’t know with certainty (ex. the correctness of actions and everything from feelings to the idea of a Deity).

Thus we can say, there is both formal and material knowledge that applies to the world outside of us, and both formal and material knowledge that applies to the world inside of us.

From those truisms we can, for the whole of our theory, say there are thus two main categories:

- The category of things that generally contains the empirical (what we sense) / material (physical objects). This category includes that which we confirm with our senses, especially our five external senses and our measurement tools (that which we can confirm via testing or direct experience with certainty).

- The category of ideas that generally contains the rational (what we must conceptualize) / formal (that which are not physical objects). This is the category of things which requires some degree of human intellect to process and deals with some degree of free-will, conceptualization, and imagination (that which exists purely or partially as thought, including aspects of feelings and pure philosophy, and is therefore that which we can’t directly sense).

Nearly everything below will arise from the idea of human knowledge/experience/understanding being split into a “two pronged fork” that considers the “physical” (material) and “logical” (formal) separately.

We will return to that concept in a moment, but first let’s talk about one more concept, that of logic and reason.

TIP: The basic concept here is things we rationalize have degrees of probability, and things we observe have degrees of likelihood. This will relate to the two basic forms of reason, induction (which deals with probabilities) and deduction (which deals with certainty). This fundamental duality shows up time and time again, because it is a duality at the core of the human experience. Each category has a different “flavor of probability.” Why? Because all matter is built from quanta, and quanta has a probabilistic nature (I assume). The why is metaphysics, the reality of the flavors of probability is empirically and logically evident.

The Two Pronged Fork of Human Knowledge; Empiricism and Rationalization

All the above to say, when trying to determine what we can know, understand, and/or experience, we will always be dealing with what we can call “a two pronged fork” (a play on Hume’s fork), where:

- Prong one is material, empirical, facts about the world and generally contains objective judgements. Ex. “The man is sitting on the chair,” or “the man arose from the chair.” It is the category of that which we can confirm with our senses without rationalization (and thus often implies a degree of objectivity).

- Prong two is formal, rational, facts about ideas and often contains subjective judgements. Ex. “1+1=2,” or “all bachelors are unmarried,” both of which are objective, or, “the bachelor has integrity and feels pride sitting patiently in the chair” (a subjective judgement). What we can only confirm with some degree of rationalization (and thus which often implies some degree of subjectivity).

Here, as noted above in relation to humans, one could consider the first prong as body (or the physical), and the second prong as mind (or the non-physical, the formal or rational).

On a table it looks like this:

| Empirical / Material (Based on Experience) | Rational / Formal (Based on Ideas) |

|---|---|

| Physics (Empiricism) | Logic (Pure Reason) |

NOTE: Above I say “generally subjective.” This is because there are subjective and objective aspects of each category. For example one can have subjective knowledge about physics in terms of frames of measurement affecting things like space-time. Likewise, one can have a somewhat objective feeling of pain, or a subjective thought and a rational objective mathematical proof. Likewise, while free-will is largely subjective, actions taken can certainly be judged with some amount of objectivity. The list goes on, so the term “generally” is used to denote complexity (and later “mixed categories” will help us to account for this complexity; for example we will call the study of beauty, aesthetics, which some call a thing of ethics, a thing of physics and metaphysics… remember this is a unique theory, not an attempt to categorize things exactly like others do).

Considering Categories of People, Places, Things, Actions, and Ideas, and the Personal, Interpersonal, Collective, and “Universal”

From here we can begin to talk about other types of classes (or categories) and note that we can know about people, places, things, actions, ideas, and feelings.

In terms of people, we can know things about ourselves, about our relationships with people, about our relationships with groups, or our relationships with the world.

Likewise, we can know things about other people, other interpersonal relationships, other collective relationships, and about the relationship of the world to itself (See personal, interpersonal, collective, and “universal”).

We can know things about the actions and reactions of these things, we can have ideas about these things, or we can use our imagination and feelings to better understand the relationships between these things.

Therefore, every concept or judgement that can be held within the grey matter of the human mind is either related to:

- A thing (a person, a place, a group). “Physics” or the category of physical things that Aristotle roots his categories in.

- A thought of a sentient thing. “Logic” or the category of thoughts.

- An action of a thing (free-will actions). “Ethics” or the category of actions.

- A feeling / intuition / imagination. “Metaphysics” or the category of sentiments.

- The relations of these things. The relationships of logic and reason which Kant categorizes… and the social relations of things (which Comte muses on and which form the foundation of the social sciences).

This forms the foundation of the “four primary categories of human knowledge” which are based on our two core classes of the physical and rational. This will all be explained in the next section.

TIP: There are “things,” and in the universe they are all made of the quanta and exist in relative position in spacetime. Some things are sentient. All sentient things “think,” “feel,” and “act” and thus we get physics, logic, ethics, and metaphysics. From here the only thing really left to do is deal with relations like Kant does, or to show how we make the categories positive and deal with social relations like Comte. Of course its a bit more complex than that, so let’s keep peeling layers off the onion.

The Four Pronged Fork: The Four Primary Categories of Human Knowledge

Knowing all the above, we can also consider a “four pronged fork” of sorts (which just speaks to the different types and mixes of rational thought and physical being).

This won’t change the basics of logic and reason, and it won’t change our two pronged fork, it will simply give us more categories to work with (this will help us to distinguish between different types of rationalizations and experiences so we don’t go trying to judge actions, morals, rocks, math problems, and data from experiments from the same exact reference frame; that would be very confusing!)

Here we can define four different categories of “what we can know” based on our two pronged fork.

This will allow us to consider what can be called in relation to a human: body, mind, “spirit,” and free-will, or generally: physical, logical, metaphysical, and ethical.

A simple way to phrase the categories, before moving on, is that every concept or judgement that can be held within the grey matter of the human mind is either related to:

- A physical thing and its motion (all physical objects and the cause and effect of Newton’s physics); The material one that relates to body. A mostly objective category. This category can be called physics, after the Greek term physis (meaning the physical world, not just Newton’s physics).

- A logical thought, rationalization, or conceptualization. The purely formal one that relates to mind. A fairly objective category. This category can be called logic, after the Greek term logos.

- “Metaphysical” impressions such as sentiments, imagination, or morals. The category that relates to the “soul.” A fully subjective category. This category is often considered as one with ethics, but we will, like Aristotle and Kant, call it metaphysics. It is the ideas upon which ethics are based. It is related to the Greek concept of pathos.

- The intentions behind the purposeful action of a thing (the choices and customs behind our conduct born from values, rules, and free-will). A fairly subjective category. This category can be called ethics, after the Greek term ethos.

Ex. based on our moral sentiments related to a sense of duty (metaphysics) we rationalize (logic) that we should use our free will (ethics) to decide to help the old lady (a thing of physics, in this case a person) cross the street (an ethical action involving material things).

By knowing about helping an old lady cross the street (material objects), and by rationalizing how this will work (using logic), and by understanding we have choice (free-will), and by connecting that good action to a higher purpose (a metaphysic moral), we have an example in which we have knowledge of all four categories.

So, to summarize: The category of things is called physics, the category of thought is called logic, the category of the will behind action is called ethics, and that category of imagination and feelings involving that which isn’t purely empirical can be called metaphysics. We can call these the four categories of human knowledge (see that link for a detailed discussion).

TIP: In physics causes and reactions are physical things, they aren’t “ethical actions.” Ethical actions are any actions involving willpower (such as all human actions).

TIP: Consider an intention, it is a thing of logic and metaphysics and appears as ethics (when action is taken). We judge based on intention, that is how the courts work, yet we can’t hold an intention in our hands (we instead have to conceptualize it rationally based on intuition and make judgements and inferences). This is one of many examples of why we really do need to consider pure reason, pure philosophy, and ethics. There is no strictly empirical reference for intention, we need to “cross forks” to have a useful understanding. We still want to root everything in the physical empiricism to the degree we can (examining evidence of all types in the court, including testimony), we just don’t want to limit all our understanding to it.

Categorizing the Physical, Logical, Ethical, and Metaphysical as Natural Philosophy and Moral Philosophy

From there we can say that all knowledge that applies to the world around us can be called natural philosophy (ex. math and science; the physics and logic of “what is;” that which is rooted in the material and considers the physical world and the logic of the physical world).

All knowledge that applies to our sentiments, imagination, or actions can be called moral philosophy (ex. the feeling of love, the concept of a Deity, or acting on Duty; the ethics and metaphysics of “what ought to be or might be;” that which is rooted in the formal and considers morals and ethical actions).

Therefore, With the above in mind, we can consider human knowledge as being subdivided into.

- Natural Philosophy which contains physics (here understood as all physical things, not Newton’s physics, but all material objects that form the aesthetic) and logic (pure reason like the pure practical reason of mathematics and theoretical physics), and

- Moral Philosophy which contains ethics (like a lawyer’s rule-set, any action, especially the actions we consider “ethical”) and metaphysics (the potentially unprovable pure morals behind the lawyer’s rules; pure philosophy, the non-physical or logical factors our ethics is based on).

TIP: Another term for natural philosophy is natural science, another term for moral philosophy is moral science. Both philosophies/sciences deal with probability, but each type is subject to a different type of probability. Consider, all things physical are subject to the probabilistic nature of matter (see quantum physics), but yet is very certain and has certain reactions (on average due to the rule of large numbers and “laws of physics”). Some logic deals with probability, other logic deals with certainty (yet it is rational, and is probabilistic in that way). Ethics deals with human action, and therefore is steeped in a mix of probabilities. Metaphysics is that which we can’t know for sure, and this nature of the unknowable is a very probabilistic thing. As we dig into more categories, we’ll find more flavors.

TIP: We can illustrate most of what we have covered so far like we do on the following table.

| Spheres / Categories | Empirical / Material (Based on Experience); Generally Objective | Rational / Formal (Based on Ideas); Generally Subjective |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Philosophy (Based on Experience); Generally Objective | Physics (Empiricism; all physical things) | Logic (Pure Logic and Reason) |

| Moral Philosophy (Based on Ideas); Generally Subjective | Ethics (Philosophy-in-Action; free-will) | Metaphysics (Pure Philosophy; sentiments and imagination) |

TIP: One can consider ethics and metaphysics, as one as moral philosophy, where ethics deals with actions, values, and related rule-sets, and metaphysics deals with the morals behind the actions, values, and rule-sets. However, not all of metaphysics deals with morals, thus (for this reason and more) it is helpful to give it its own category like Kant does in his Fundamental Principles [AKA Groundwork] of the Metaphysic of Morals.

TIP: All of the ontological categories of Aristotle (reality) and Kant (concepts) can fit in one or more of our categories above (this is why I call them fundamental/primary). Consider Aristotle’s categories: Substance (physical), Quantity (physical and logical), Quality (any), Action (physical and ethical), etc. As we can see most of Aristotle’s deal with the physical. Meanwhile some Kant specific categories, like those dealing with modality, are purely rational. Now consider a quality like “happy,” or the subject “happy rock,” those qualities are metaphysic. What Kant and Aristotle called fundamental categories can be placed in our system. No one theory is right, instead they all inform each other with the ideal end result being insight for the reader!

Ancient Greek philosophy was divided into three sciences: physics, ethics, and logic. This division is perfectly suitable to the nature of the thing; and the only improvement that can be made in it is to add… [metaphysics]. – Kant

With that in mind, and to offer more insight before moving on to other aspects of knowledge, the categories above can be described in more complex terms as:

- THE PHYSICAL (“PHYSICS”): Empirical and Material Physical Things (that which we can sense directly or measure). Ex. “The bachelor is sitting in the chair.” Any observer can confirm this with their external senses (or with scientific measuring tools). Knowledge of this type is therefore objective in most cases.

- THE LOGICAL (“LOGIC”): Formal Rationalizations; AKA Pure Thoughts. Ex. “All bachelors are unmarried.” We can’t confirm every bachelor is unmarried, but we know this logically because being a bachelor implies being unmarried. Our reasoning might be sound, but we can’t confirm it with our senses. Knowledge of this type is often objective, but it can delve into pure theory and become subjective.

- THE METAPHYSIC (“THE PHILOSOPHICAL”): That which is Empirically or Rationally Knowable to us alone, but formal and requiring rationalization to those outside of us; Feelings / Morals / Values / Intuitions / Imagination / Pure Philosophy (what ought to be, what might be, or what we feel or imagine there is). Ex. “I feel sad for the bachelor, he must be lonely in that chair,” or, “the bachelor is following his heart waiting for the right partner, he has integrity,” or, “imagine a perfect vacuum.” Our feelings about the bachelor are true for us, but they aren’t objectively true for all observers. The bachelor’s moral qualities and the sentiments that arise may be “true” for him, but they are somewhat subjective and they are not confirmable by outside observers directly (only his related actions would be). Meanwhile, we know pure vacuums are useful to consider in physics, but they can’t be experienced directly (we have to imagine them and rationalize). Like it will be with ethics, metaphysics relates to the other categories in many cases, it involves emotions (which are partly physical), it involves rationalization (which are related to logic), and it can compel ethical action, but for our purposes we can consider pure metaphysics of its own category (a category that has incalculable degrees of uncertainty). This category is subjective for the most part.

- THE ETHICAL (“ETHICS”): The Formal Rule-Sets Behind Actions born from Free-Will; generally pertaining to our concept of right and wrong (the choices and customs behind our conduct). Ex. “The able bodied bachelor chooses to arise from the chair,” or, “the married person didn’t flirt with the bachelor because their morals compelled them not to act.” A human has some degree of free-will, thus the able bodied bachelor can choose to get out of the chair (unless something is preventing him, such as a law; perhaps the action of sitting in chair is “unethical,” thus, based on a custom, the bachelor chooses to arise using his free-will; perhaps the national anthem is playing?) Likewise, the married person choose not to flirt with the bachelor, it was a possible choice, but was deemed “unethical” due to a set of customs and values. Ethics are the customs behind our conduct, they are not the physical action itself, nor are they the laws themselves, nor are the they they logic behind those rule-sets, nor are they the morals and values upon which our actions are based. Those can be thought of as physical, logical, and metaphysical aspects of ethics, but they are not pure ethics themselves. NOTE: As you can see, like with “metaphysics,” this category is hard to define in isolation, because most human action generally involves aspects of physics, logic, and metaphysics. This is one reason why we considered our two-pronged fork first (we CAN explain everything as a two pronged fork, but having the four categories will help us to make important distinctions later). NOTE: This category is generally subjective, but has objective aspects. Consider a court case where a person is judged on intent and action. The will to act was subjective, but the actions can be objectively judged to some extent.

Introduction to the Mixes of Categories and Other Details

With the above in mind, we can actually consider mixes of categories to produce a wide array of possibilities and to allow us to categorize complex things like the logical rule-sets behind ethics, the moral values behind ethics, the physical emotions related to sentiments, or the action born from physical reflexes.

We can also use these concepts to work with complex judgments which consider a mix of categories (where knowing the category of a term used in a judgement will help us understand its qualities and thus some qualities of the judgement).

For example: Imagine that the bachelor felt sad, so he decided to get up from his chair, and observer A watched this. Meanwhile, a second observer, observer B, recorded the events and the testimonies of the bachelor and observer A.

Observer B could then state with a high degree of confidence, “given my research, there is a high degree of certainty the bachelor got up from his chair because he felt sad.”

It is objectively true he preformed the action of getting up, but somewhat subjective and metaphysic that he “felt sad.”

This honest statement is grounded in fact, but necessarily uses a mix of objective and subjective information (as it was based on not only observation, but on sentiment, human action, and testimony).

Because the statement considered ethics (choosing to get up) and metaphysics (feeling sad) to some degree, a bit of rationalization was required to explain the empirically observable aspects of the event.

By understanding categories, concepts, and rule-sets pertaining to truth, we can then begin to apply logic and reason to draw inferences from the world around us, denote certainty, and differentiate between subjective truths, objective truths, opinions, theories, facts, emotions, “counterfeit information,” and other types of truths and non-truths.

At the end of the day, everything is either true or it isn’t… yet, not everything that is true can be proven. This means for all the considering we can do on “what we can know,” there is no guarantee that we can know everything (in fact there is an assurance we can’t)… and that is where other technologies like skepticism come in!

Below we explain “a basic theory of knowledge” (an epistemological theory of what we can know and how we can know it).

More Details on Mixed Categories

One sort of problem we have with above categories is that they don’t account for concepts like aesthetics (which is sort of physical and sort of metaphysical), or the empirical aspects of emotion (“the impressions of passions and sensations”), or the speculation of cosmology (speculation about the universe).

To account for that, we are going to describe those things as a mixture of physics and metaphysics; what I call “The Physics of Metaphysics” and “the Metaphysics of Physics.”

The same logic goes for ethics which, as it deals with human action as an ends, also deals with a mix of categories.

Consider, ethics is a purely formal thing, as it considers thoughts and feelings, but it has material results (the results of human action born from free-will or custom are empirically observable, and thus that aspect relates to material physics). Other aspects of ethics include moral judgements of actions (which relate to metaphysics and logic), and logical rule-sets (which relate to logic). Suffice to say, each category has its complexities.

The benefit of our system of categorization is that it addresses all the above complexities via mixed categories where we consider the physical, logical, ethical, and metaphysical aspects of each physical, logical, ethical and metaphysical category.

For example, as noted above, we can consider the empirical aspects of emotions or cosmology, where the empirical aspect of emotion deals with the chemistry of how an emotion arises (and the physics of how it affects our neurology), and the empirical aspect of cosmology deals with what we know about quantum physics and astronomy (which we can thereby use for proper inductive reasoning).

Considering Material and Formal Physics, Ethics, Logic, and Metaphysics

Here we could jump right in and consider the physics, logic, ethics, and metaphysics of physics, logic, ethics, and metaphysics.

However, there is one step in-between to consider, and that can be done by considering the material and formal divisions of physics, logic, ethics, and metaphysics (AKA these are 8 categories of human knowledge):

| Spheres | Empirical (Material sphere of facts based on experience) | Rational (Formal sphere of facts about ideas) |

|---|---|---|

| Material Natural Philosophy | Material Physics (Practical Material Empiricism) the Physics of Physics | Material Logic (Practical Material Logic) the Physics of Logic |

| Formal Natural Philosophy | Formal Physics (Pure Formal Empiricism) the Logic of Physics | Formal Logic (Pure Formal Reason) the Logic of Logic |

| Material Moral Philosophy | Material Ethics (Practical Philosophy-in-Action) the Physics of Ethics | Material Metaphysics (Practical Material Philosophy) the Physics of Metaphysics |

| Formal Moral Philosophy | Formal Ethics (Pure Formal Philosophy-in-Theory) the Logic of Ethics | Formal Metaphysics (Pure Formal Philosophy) the Metaphysics of Metaphysics |

Considering the Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics of the Physics, Logic, Ethics, and Metaphysics (the Fundamental Transcendental Categories)

With the above models in mind, we can subdivide this again.

This time we won’t just consider the material and formal of each category, we will consider the physics, logic, ethics, and metaphysics of physics, logic, ethics, and metaphysics.

This last sub-division will unveil the true character of our four category model (16 variations). We will from here be able to compare and combine terms, propositions, and inferences, to construct complex mixed systems, and to categorize anything we can know.

NOTE: There is some serious over-lap between categories here (which for me is a sign that this level is a good level to subdivide into). What is the difference between the physical aspects of metaphysics and the metaphysical aspect of the physical? Great question! Part of me says one contains F=ma and the concept of beauty and the other contains force and a beautify object. The other part of me says, these categories as simply [in Kant’s terms] transcendental and bleed into each other to such a degree that we should treat the physics of metaphysics and the metaphysics of physics as being of the same transcendental category. I assume this will become clear over time, for now each of the 12 gets its own definition, but can none-the-less be considered transcendental in the cases where we get a mixed category (like the metaphysics of physics) and pure when we get a pure (in the sense of “only” not in the sense of “formal rationalized idea”) category (like the physics of physics).

TIP: This section still needs work, take it as an example, not gospel (the general idea here is right I think, but I’m sure there is much more to uncover).

- The Physics of Physics (material physics) describes that which is (like a rock); the purely external that can be experienced directly (or via measurement tools). All action that does not involve free-will is this. Literally physics and also “being”.

- The Logic of Physics (pure logical physics) describes the logic of that which is (like F=ma, the logic of how a rock falls on earth); describes the logical aspects of theoretical physics (the mechanics of physics).

- The Ethics of Physics (ethical material physics) describes the art of correct experiment and measurement (for example the art of employing the scientific method); also the social sciences touch upon this category. Also could describe things like how to treat the earth, or perhaps even how a positive and negative charge attract. Aspects of the art of appreciating beauty and earthly pleasures (aesthetics).

- The Metaphysics of Physics (pure metaphysical physics) describes aspects of theoretical physics; also can be said to contain aspects of the art of appreciating beauty and earthly pleasures (aesthetics); our emotions arise from here (on a chemical level).

- The Physics of Logic describes the literal equations we use (how formulas work).

- The Logic of Logic describes the formal logic behind the equations.

- The Ethics of Logic, the best ways and best practices of using logical rule-sets (from math to rhetoric and reason).

- The Metaphysics of Logic, from theoretical mathematics to theories like Gödel’s, to theories of influence, rhetoric, and reason.

- The Physics of Ethics, practical ethics in action (the action).

- The Logic of Ethics, the logic behind the action.

- The Ethics of Ethics, manners and such (considerations on the action).

- The Metaphysics of Ethics, the moral and theoretical considerations of ethical rule-sets.

- The Physics of Metaphysics, morals in action, practical philosophy, emotional reactions (that which one can experience even if they can’t define or measure); the Church is a thing of physics and metaphysics.

- The Logic of Metaphysics, epistemology, the logic behind theorizing on what we can’t know for sure and that which we can.

- The Ethics of Metaphysics, considerations for actions based on morals.

- The Metaphysics of metaphysics, the study of that which we know we cannot know in any other way except internally; includes pure theology.

| Spheres | Material Natural Philosophy | Formal Natural Philosophy | Material Moral Philosophy | Formal Moral Philosophy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material Natural Philosophy | The Physics of Physics | The Physics of Logic | The Physics of Ethics | The Physics of Metaphysics |

| Formal Natural Philosophy | The Logic of Physics | The Logic of Logic | The Logic of Ethics | The Logic of Metaphysics |

| Material Moral Philosophy | The Ethics of Physics | The Ethics of Logic | The Ethics of Ethics | The Ethics of Metaphysics |

| Formal Moral Philosophy | The Metaphysics of Physics | The Metaphysics of Logic | The Metaphysics of Ethics | The Metaphysics of Metaphysics |

TIP: We can put the complex category “social” in a number of categories, thus accounting for economics, politics, food distribution, group psychology, and such… or we could loosely file all of this under ethics. I prefer to think of “social” as a category that is predicated on the four primary (and 16 sub). The physical world is reality, then because there are sentient beings, there is rationalism. Because there is rationalism, there is metaphysics (as there is both a mathematical aspect and an knowledgeable aspect to thought, both sentiments and pure logic)… and because there is all of this, and because beings can act, there is ethics (which is action based on thought and sentiment). So, “social” (what arises from human as a social sentient creature) is not outside the categories, it is within it and predicated on it in some ways, and in other ways it is simply “ethics.”

What we can know by knowing what category an object or idea is in: The physical, logical, ethical (metaphysics as it relates to human action or conduct), and metaphysical are all classes that contain different types of knowledge. As such, “what we can know” about things in each category differs by category. The same is generally true for the related categories of moral philosophy and natural (and the sub-categories noted on this page). The physical includes what we can know with things like physics and observation (where things have probability in the way quantum objects do and have observable objective certainty), the logical with things like mathematics and logic (where proofs are objective, but logic is none-the-less a thing of pure ideas), the ethical with things like social science and experience (where we get a mix of the problems and perks of each other category), and the metaphysical with things like individual experience and imagination (where we can have useful knowledge, but deal with unknowns like we do in induction; where everything is at best probable). Information about the physical world possesses some aspects of certainty and can have logic applied to it (what makes the science of physics possible), meanwhile metaphysics dabbles in the probabilistic and uncertain. All this to say, knowing which of the transcendental and categorical “primary” classes information is in, tells us about what type of knowledge we can expect to be gained from studying the properties of objects in that class. It also gives us information about how objects and ideas in different classes relate. And then of course, the same is generally true for any type of category of epistemology, such as the one’s of Aristotle and Kant.

TIP: “I think therefore I am,” and one might, say “I feel therefore I am.” Our thoughts and feelings are subjectively real for us and we can be very certain about them. Meanwhile, the rock in front of us is objectively real. Sure, our external senses could be tricking us, but so could our internal ones. All types of knowledge are useful, but each type has a different quality! Alone each type only paints part of a picture, the full cannon of human knowledge, experience, and understanding can only be gleaned by crossing the categories.

TIP: Below are four videos. One gives a “map of philosophy,” one a “map of the maths,” one a “map of chemistry,” and one a “map of physics.” All philosophy is essentially “of the metaphysics” to some extent, but regardless we can take each category from the philosophy below and place it under our categories above. Does it deal with ethics and action? Well then it goes in a category with the term “ethics in it.” Does it deal with the foundational logic of metaphysics? Well that is a sign it goes in the logic category (generally under the metaphysics of logic or the logic of metaphysics). Likewise, we can do the same for the other videos. Are we discussing chemistry? Well chemistry is a physical system, so it will go in cats that have the word physics in them, the ethics of physics perhaps (which is the category of physics that deals with action… and what is chemistry if not physical non-sentient things in action?). Are we discussing physics? Most of that will be covered under non-sentient action and the physical category itself, but of course there are lots of metaphysical aspects of that. Lastly, for the maths, while they are all rooted in logic, they also often relate to metaphysics. After-all theoretical physics is a thing of logic, but also of metaphysics and physics. Sure, the basics like a number itself are purely arational (but don’t they also speak to the physical act of counting?) If we consider theoretical math, it is metaphysic. When we consider change there are aspects of physical and non-sentient action going on. Yes, these categories transcend, and we’ll need to consider mixed categories, but this is why we use transcendental categories for the complex things that arise from the simple dualities. With that all in mind, we can take the systems in the videos below and place each category or subject or sub-set and place it neatly into our categories above. If we couldn’t, then this wouldn’t be a very good “system of fundamental categories of being and knowledge.”

The Map Of Philosophy. A basic overview of the branches, see our more complete list below. Notice the colors they use in their map. Yellow for logic, green for the physical, blue for metaphysics… these colors are consistent with western element theory and astrology. Are they convention or not? We won’t muse on that question of metaphysics, but let us just say, I know I did not pick them at random for our theory. The colors like the subjects have meaning. All philosophy is the art science of moving toward knowing and exploring that meaning. The Map of Mathematics. Plato tells us to start with mathematics. One of the many smart things he suggested. Math is a very simple analogy for all real systems. If we can categorize math into the applied/empirical and pure/rational we are well on our way to connecting all the dots… and we can, and this video does, and this page connects those dots. No, I don’t yet have a master list of everything categorized, but if you understand this system you can none-the-less categorize everything (as I will do when I’m fully ready). The Map of Chemistry. Arguments for a virtual simulation aside, while we can argue philosophy and math, it is hard for any empirical minded person to argue against chemistry. It is about as real as it gets… and guess what? The fact that it is the real basis of everything means that fitting it into our categories is very easy and symbolic of what we are doing with other fields to create a full list. A protein is real, made of real elements and real chemical re-ACTIONS, meanwhile the logic behind it is logical, and the application can be considered, and the metaphysics of it, etc. All systems, real and theoretical can be placed in the categories. Now, is this useful? Well, that is a whole other question. The Map of Physics. If we can map out chemistry, then of course we can map out physics in a similar way. Both are physical systems in-action that form the foundation of being.Additional Notes on the above

TIP: Each phrase above represents a category in which to place all human knowledge that belongs in that category, so each example is only some of the possible examples. Consider every subject one studies in school, and every field one enters into after, can be categorized below. Knowing this we will be able to see things such as “why aspects of the social sciences are elusive and uncertain, despite being useful and true,” and more. Consider, people are physical beings, and so are economies and markets, but the relations between those physical bodies are not purely material, and thus uncertainty is introduced (and thus truths become probable and not externally fully knowable).

NOTE: There is some serious over-lap between categories here (which for me is a sign that this level is a good level to subdivide into). What is the difference between the physical aspects of metaphysics and the metaphysical aspect of the physical? Great question! I’ll answer that here and in the next notes (as i’m working on phrasing it and thinking on it). Part of me says one contains F=ma and the concept of beauty and the other contains force and a beautify object. The other part of me says, these categories as simply [in Kant’s terms] transcendental and bleed into each other to such a degree that we should treat the physics of metaphysics and the metaphysics of physics as being of the same transcendental category. I assume this will become clear over time, for now each of the 12 gets its own definition, but can none-the-less be considered transcendental in the cases where we get a mixed category (like the metaphysics of physics) and pure when we get a pure (in the sense of “only” not in the sense of “formal rationalized idea”) category (like the physics of physics).

NOTE: The categories below should explain themselves with a little critical thinking. The physics of physics should be thought of as “the physical aspects of physical things.” Likewise, the ethics of physics is “action as it relates to physical things.” So the physical aspects of metaphysical ideas (sentiments and imagination) speak to real things like music, art, feelings as chemical reactions, and the metaphysical of physical things are more like the theory of physics, the theory of music, the theory of art (aesthetics). Both those cats are “of material natural philosophy and formal moral philosophy,” but they each express a different aspect of this relation. The way these categories bleed into each other is “transcendental.” See “the spheres of human understanding” for more on that.

NOTE: These categories represent different “flavors.” Some flavors are pure (like the physical aspects of the physical; “the physical”) and some flavors are mixed (like the metaphysics of the physical). Mixed categories represent where transcendental knowledge and be categorized. The transcendental aesthetic, that is in the metaphysics of physics (and bleeds over into the physics of metaphysics). A synthetic a priori, that falls in the same category (it speaks to both the physics of metaphysics and the metaphysics of physics). Lastly, geometry, music, and color all have both physical and metaphysical qualities, aspects of them are therefore “transcendental.”

Some Logic Behind What We Can Know (a Detailed List of Epistemological Laws)

With the above in mind, we can make the following [generally] true statements about human knowledge (some of this will be repeats of the above, some of it will be new; the goal will be to better understand the different types of terms/concepts we can place in our categories of knowledge):

TIP: This section is meant to deal with nuance and includes some repetition of what we already covered above.

First:

- Human knowledge is everything that can be known for sure or understood to any degree (even if only theoretically).

- There are two ways to know things, via experience and/or thought.

- All knowledge that we can know directly via our senses, internal or external, is empirical, and all knowledge that we have to imagine to any degree is rational.

- Of the rational there is that which is rooted in experience, and that which is pure rationalization (pure imagination).

- When we know something about what we experience directly, we can call the truths that arise “facts based on experience,” when we know something based on thought, we can call what arises “facts based on ideas.” In science, we want to verify based on experiment to ground theories in “facts based on experience,” but that doesn’t mean that Pure Reason (pure ideas) isn’t useful (more on that below).

From there we can say:

- Human knowledge begins with the physical, material, and empirically sensible. We are made of quanta, not magic, thus it stands to reason that everything arises from “the physics/the physical” (so to speak). This is to say all knowledge begins with the external world around us that we can sense with our senses, even if it doesn’t end there.

- We can also consider our “empirical” internal senses, what we Hume called impressions of sensation or original impressions, like the feeling of pain. These are the internal feelings that are natural, don’t require rationalization, and arise from chemical reactions to stimulus (they don’t require rationalization and instead are a sort of reflex to stimulus that we can intuit the impression of immediately).

- We can call those things we sense directly, internally or externally, and know immediately intuitions (similar to what we know today as sensory memories). The things we can confirm directly via experience, internally and externally, and don’t require rationalization, form the basis of our knowledge.

- What we know from our external senses, that which can be confirmed via falsifiable experiment is positive empirical knowledge. Knowledge gleaned directly from a measurement tool is not exactly the same as direct experience, but it can generally be considered positive. That which we intuit from our own internal senses without rationalization is also a type of empirical knowledge, but it notably is harder to prove (as it must be proved by ourselves alone or proved with a probability based on testimony and social experiments).

- Knowledge that comes from outside of us that is confirmable by others without rationalization is objective, meanwhile knowledge that comes from within us is confirmable only by us and is subjective. Knowledge that uses a mix of the two, and thus requires rationalization, is mixed. Ex. I am cold (internal; subjective), or, look there is a rock (external; objective), or, that rock is beautiful (external; subjective), or, look at the data from this measuring tool (a mostly empirical extension of the senses), that atom has strange geometry (external via a measurement tool; objective… but the term strange is a little subjective), or, every time we repeat this social science study the data shows that the feeling of belonging and the need for approval drives people to obey authority (external/internal via experiment, testimony; objective/subjective; AKA “mixed”).

- On Impressions from our internal senses there are two types. The impressions of sensation (empirical impressions), or original impressions (as noted above), are the feelings we get from our five senses as well as from our internal senses of the same sort, such as our immediate sensations of pain and pleasure. These are sort of impressions of reflex, they are automatic (see our many internal and external senses according to science). Meanwhile, there is another type of impression. Impressions of reflection (rational impressions), or secondary impressions, are impressions from reflections rationalized based on our original impressions. Secondary impressions (impressions from reflection) are the emotion we feel from considering ideas (they are emotions we feel based on rationalization). Here we can consider not only the passion we feel thinking about a concept like Justice, but the impressions we feel like when we witness and consider the just act of another. In this sense they are the mostly “metaphysical” aspect of our feelings, the desires, emotions, passions, and sentiments that arise based on experience and rationalization (or in modern terms, emotional biases based on experience, the emotions related to them, and the impression they leave). NOTE: Hume will question whether or not justice has any sentimental meaning in a world that knows only equality, there is a whole conversation here that we will cover below. For our purposes, the emotions related to a moral quality (a virtue) like justice and the concept of justice itself can be considered to be of both physics (the chemical emotion) and metaphysics (the concept of justice), while also not removed from ethics or logic, and can be considered secondary impressions.

- Original impressions from our internal senses are empirical (but formal; they aren’t tangible material objects), secondary impressions from our reflection, although they have an empirical quality when we feel the related emotion, are partly rational (and formal); i.e. secondary impressions are mostly metaphysical (but with a physical root). They come from rationalization, and they compel ethics, but they are (if we have to place them in one category and not a mix of categories) “of metaphysics.” Consider, if we think of complex ideas related to Duty, then “feel a sense of Duty” the emotion itself is empirical, but the pathway to emotion, the rationalization, is… rational/formal.[4] However, “a sense of Duty” is not “1+1=2” and thus it helps to categorize in a separate category of moral philosophy and metaphysics. NOTE: See Hume’s Delicacies of tastes and passion and other works, he called internal passions and sensations like feelings impressions; see also Smith’s moral sentiment, it is an empirical theory of impressions so-to-speak; both authors are giving an empirical theory of “metaphysics”). NOTE: While we can feel sensations and have tastes, sentiments, and passions, they don’t exactly have the same qualities as a rock, and that is the point here. Below we will categorize these in different types of impressions and rationalizations in different categories and we will explain “mixed categories’ which help account for things that have both a formal and material nature.

- We can use our understanding to make sense of sensory data, internal or external, physic or “metaphysic” (“conceptualizing” and “rationalizing” by associating basic sensory data; as we do in our memory process when we store and recall data). In this process we can use our imagination as we creatively combine, copy, transform, and transpose ideas. We can imagine spacetime, or we can imagine a fable, or we can imagine a secondary impression as a form of the virtue of True Justice or as Duty or Honor (and then tell the tale of how King Arthur displayed these qualities to inspire the next generation). Are these shared formal passions that we weave into metaphors pertaining to the natural and moral important, yes! Are they empirical and material, no! These things are partly imagined and rationalized. These things are metaphors, and they inspire us and speak to real things, but they are not themselves real in the same way a rock is. Metaphors are a thing of “metaphysics.”

- Here we can consider that our senses could be tricking us, and so could our rationalization. That is why we want to consider different types of data, be skeptical, use positive experiment, root things in objective empirical data, and consider both the empirical and rational for what they are.

- Of imagination there are two types, there is the type that uses empirical data to imagine variations of real things, and the type that is pure imagination. For an example of the real type, imagine you had only ever seen a blue ball and a red box. Here you could imagine a red ball and a blue box even though you had never seen either (but, if you had only seen the color blue, imagining something red would likely be impossible, as you would have no frame of reference for understanding this). For an example of pure imagination, imagine existing in the spacetime of the 10th dimension 10 billion years form now. Here we can be skeptical that it is possible to imagine ideas based on nothing, but we can at least note that there is a class of things we can know that is far removed from direct experience (the class of metaphysics; more on metaphysics and imagination below).

- On the above, like Kant does, we can call those things based on direct experience “intuitions,” and those things that were rationally conceptualized based on intuitions concepts… but for our theory we are going to call them both concepts (denoting empirical intuitive concepts and formal rationalized concepts as necessary). Another word for “a concept,” when dealing with it in logic is “a term.“

- One way to discuss terms or concepts is to use a symbol. Symbols are simple signs that can stand as a placeholder for many complex ideas. In other words, each symbol has anchored to it a number of different judgments about different categories of things. There are simple symbols like F (for force) or complex ones like “human knowledge” (which stands for everything discussed on this page and more). See: Language as symbolism. We can in turn place a number of symbols in a single judgement and we can then reason based on series of judgments (therefore actually rationalizing a myriad of complex ideas).

- When we start dealing with complex mixes that have uncertainty, we have to accept that we are in territory where we can’t know for sure. Instead of knowing for sure we have to use experiments to test for outcomes and look for theories that are useful and not useful. If F=ma always works, it doesn’t HAVE to be a law in all possible worlds, it can just be useful in most contexts.

- In all categories of life we can employ experiment, rationalization, testimony, metaphor, symbols, logic, reason, judgements, etc to better understand useful human knowledge.