The Philosophy Behind the Types of Governments

The Philosophy of Governments

It can be very attractive to have a list of government types, but yet that list may teach a person very little. Here instead is a look at the philosophy behind the government types that create that list.

For a simpler list and look, see our page on “the types of governments.”

Illustrating the Classical Government Types

One way to show the classical government types, here rooted in Plato’s theory is like this.

IMPORTANT: This table below is my own theory extracted from Plato’s work (there is no one way to illustrate the classical types; not even Aristotle and Plato fully agreed, see a discussion on what I call “the types of tyranny“).

| Plato’s Five Regimes Expanded | Correct (lawful; Ruled in Line With the General Will) | Deviant (Special Interest Before the General Will) |

| One Ruler or Very Few Rulers | Monarchy /Aristocracy (intellect and wisdom based) | Despotic Tyranny (fear based) |

| Few Rulers; the Ideal Polity | The Polity (a Mixed Republic the draws from the “correct” forms to protect against tyranny). | NA |

| Few Rulers; a Military State | Timocracy (honor and merit based) | Tyrannical Timocracy (military state gangsterism; like a despotic Junta) |

| Few Rulers; a Capitalist State | Oligarchy (wealth based) | Tyrannical Oligarchy (greed based; a Plutocracy) |

| Many Rulers | Democracy (pure liberty and equality based) | Anarchy (pure liberty and equality based) |

NOTES: There is more than one way to understand some of the terms on this page, and there is more than one way to illustrate things. Thus, all this should stand as insight and not gospel truth. The goal is to give an overview of the types of government accounting for both their historic and current meanings, and to offer insight into what different philosophers thought about them. It is a work in progress. Compare our page to Wikipedia’s Forms of government (that is, for me, one of the best types of governments lists on the internet) and then compare it to our attributes of government page. All general truths will be the same, but each author is bound to explain things in a slightly different way (after-all the philosophers gave differing definitions and today governments in name are not always such in action). On that note, I also think this site does a pretty good job as they differentiate between economy, politics, and authority.Marx and Mises both thought socioeconomics was at the core of the government types, Aristotle, Machiavelli, and Hobbes thought of the forms as being about “who rules” and “who votes on laws”, and Plato and Montesquieu thought them to be about “the virtues of state and the spirit of the laws”. In practice, all these “attributes” affect a government’s type. Below we consider the many different social, political, ideological, and economic attributes of government that help define the real and philosophical forms of government. That said, starting with the classical foundation is important, so we’ll do that first.

How to Understand the Basic Forms of Government (Classical Power Sources)

Although even the ancient Greek philosophers each understood the forms of government in slightly different ways (for example Plato the idealist defines “the five regimes” by their virtues in his Republic and Aristotle the realist by “who rules”), generally speaking:

The classical forms of government can be said to be based on the realist question “who rules?“, which can itself be understood by two closely related questions “how many people get a say?” and “who says so?” (where “who says so?” means “who votes on laws?” and “who makes the laws?“, not “who votes for elected officials who make the laws?”; see why America is a Republic and not a Democracy).

Otherwise, they can be said to based on the idealist questions “what are the virtues of the government?”

With that in mind, in the Aristotelian and Machiavellian realist theory, the three classical forms of government are Monarchy (ruled by one), Aristocracy (ruled by the few), and Democracy (ruled by the many).

If one wanted to think of each modern and historic nation as being “a mixed government” rooted in one of these, they would have the basics down.

From there we could look at different “attributes”, but before we do that here we are going to dive deeper into these classical forms, the different philosophers takes on them, and how the other forms a derived from this simple three way split.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

TIP: The forms of government can be understood may ways, including by reading Book 3 of The Social Contract by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (due to his chronology he is easy to read and describes the forms well). Also useful is Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws Vol. 1, as he offers much more detail; however his theory is more complex. With that said, it is Plato and Aristotle who originally shined a light on the forms in their Republic and Politics respectively. So while a modern realist will likely prefer to focus on governments-in-action (noting attributes like economy, socio-economic systems, power distribution, and power structure; other key attributes that define real governments), we are going to lay out the philosophical groundwork first. Thus, we will begin our discussion with the Greek forms and seek to understand those theories first, then move to the enlightenment philosophers, then to the economists, then describe the in-action attributes that define modern governments. See social contract theory for more information.

What is Government? Government is the will-in-action of the people. It is the part of the state that acts on behalf of the people (ideally in accordance with “the General Will“; i.e. the common good, not the majority opinion). See a theory of government and a theory on the separation of powers. This can, metaphorically, be related back to the spheres of human understanding, where we can say “government is not the morality or logic of the people, but it is the ethics-in-action that effects the physical”.

The Classical Correct and Deviant Forms of Government

Each of the classical forms (Monarchy, Aristocracy, Democracy) can be separated into two types by asking one last question, “whether or not it is ruled justly” (where “just,” or virtuous, is well interpreted as “ruled by law in favor of the people”).

This gives us what Aristotle called “correct” (ruled by law for the people) and “deviant” forms that put special interests before the law and the people.[7]

Wherever law ends, tyranny begins. – John Locke 1689, discussing “correct” governments and inalienable rights.

TIP: All forms that are “correct” are generally liberal and in the spirit of Republicanism, those that are incorrect generally aren’t (although oligarchy and anarchy, when restrained within a mixed government, can be seen as fitting within the spheres of liberalism and republicanism). The most truly liberal and Republican government is of course the “mixed-Polity” all the philosophers will essentially suggest.

Plato’s and Aristotle’s Forms of Government

According to the Greeks there are five or six (depending on how you count them) possible classical forms of government based on “who rules” (or rather, speaking generally, there are three forms, each with one correct and one deviant form).(Politics III.7, adapted from Plato’s Statesman 302c-d):[8][9][10]

Keeping in mind that the Greeks didn’t [always] draw little charts like the ones below to describe the governments and that this is an attempt to translate their theories into a few tables:

Plato Defined the Forms like this (yes, off the bat Plato swaps some terms preferring that we base this on virtue rather than “who rules”, but bear with it until we get to Aristotle):

| Correct (lawful) | Deviant (corrupt) | |

| One Ruler-ish | Monarchy /Aristocracy (intellect and wisdom based) | Tyranny (fear based) |

| Few Rulers | Timocracy (honor based) | Oligarchy (greed based) |

| Many Rulers | Democracy (pure liberty and equality based) | Anarchy (pure liberty and equality based) |

NOTES: Plato and Aristotle don’t really distinguish between Democracy and Anarchy (I think to make a point) and for Plato Monarchy and Aristocracy may as well be the same thing (even though he recognizes that the “who rules” question applies, their virtues to Plato are the same). Lastly, Plato’s Kallipolis or Polity (his ideal mixed government meant to rule over his “ideal Republic”) was a mix of Democracy, Oligarchy, and Aristocracy, so it doesn’t really fit in the chart.

For educational purposes only, an illustration of Plato’s five regimes.

Aristotle’s Forms as He Defined Them look like this:[11]

- One: Kingship (a virtuous King, a Monarch) or Tyranny (a Despot who puts their interest before the law and the people).

- Few: Aristocracy (a virtuous elite) or Oligarchy (elite that rule by wealth and power).

- Many: Polity (virtuous rule by all, a lawful mix of Constitutional Democracy, Oligarchy, and Aristocracy; “a Mixed Republic” like the U.S.) or Democracy (chaotic rule by all, mob rule or anarchy; the tyranny of the majority; the Greeks thought of Democracy as being akin to anarchy… but this makes sense in ways, Pure democracy implies extreme equality and liberty, and nothing works well in extremes).

| Correct (lawful) | Deviant (corrupt) | |

| One Ruler | Kingship | Tyranny |

| Few Rulers | Aristocracy | Oligarchy |

| Many Rulers | Polity (Mixed Republic) | Democracy |

NOTES: Aristotle, like Plato, treats Democracy and Anarchy as essentially the same thing. Here his Polity (his perfect mixed government) is placed in the many rulers box, as essentially he wants to show that the seemingly great sounding Democracy isn’t good, but that doesn’t mean “the many shouldn’t rule”. It is then, for the Greeks, this ideal mixed Republic that allows for the best system which best represents “the general will“…. of course, this is just the type of thing that confuses people in modern times, making them think that “Democracy” is somehow inferior to “Republicanism”… it isn’t. As we will note below, the actual conversation we are having today is “how should the mixed-Republic look” should it be more toward aristocracy or more toward Plato’s Democracy.

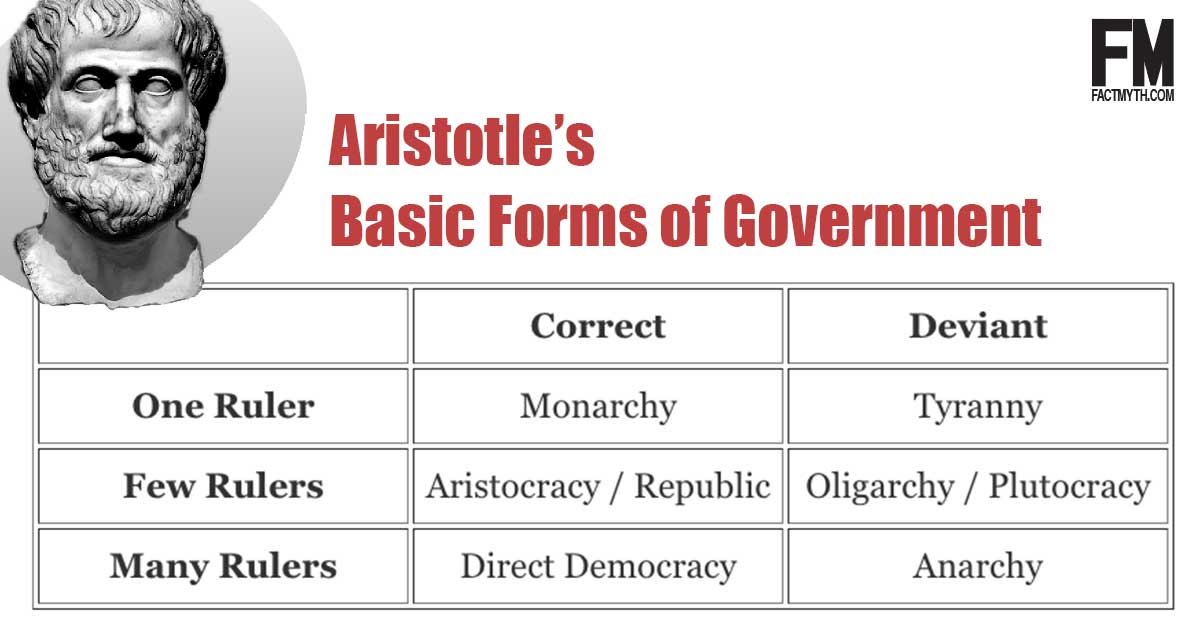

To translate Aristotle’s Forms of Government into modern terms (we use a translation in the header image at the top of the page) it looks like this:

| Correct (lawful) | Deviant (corrupt) | |

| One Ruler | Monarchy | Tyranny / Despotism |

| Few Rulers | Aristocracy (what we typically think of as a Republic; where I would put the ideal mixed Republic) | Oligarchy / Plutocracy |

| Many Rulers | Direct Democracy | Anarchy |

NOTE: In the above chart we are taking Aristotle’s forms and modernizing them. For me, this is the one that will connect best with what we think of as the forms today (the other theories are good, but need to be understood with nuance). Both Aristotle and Plato consider Direct Democracy to be Anarchy, and they use the terms Kallipolis/Polity to describe a constitutional government that is a democratic type of aristocracy (what today we call a Republic). So, if you are taking a test, use “the forms as Aristotle defined them” above (or as shown in the image below). If you want to understand the modern forms in a way that will make all the philosophers and modern the modern terms we use make the most sense, then use the “modern terms” chart above.

TIP: Aristotle and Plato didn’t agree on everything, but they did essentially agree on the forms of government (with Aristotle summing up Plato’s work and making some key distinctions). Aristotle’s forms of government have essentially been used by all great philosophers from Livy to Machiavelli, to Locke, and beyond. Thus, they provide a vital foundation upon which all other forms rest (aside forms based on specifics like market structure and trade).

TIP: For another view, so we have a strong foundation before moving on, here is another look at the forms of Government of Aristotle. Note this chart translates Deviant and Corrupt to “Perverted”. We are translating a Greek theory from a over 2,300 year old text, don’t get hung up on specific terms. Especially don’t get hung up on the term democracy, as we will explain, there are many different types that actually sit in fully different parts of the chart! For the Greeks Democracy is Pure Direct Democracy (an almost anarchistic state).

Here is a detailed version of Aristotle’s original forms. Now that you know the basics, this will make more sense.

TIP: For more reading, see our page on how democracy can lead to tyranny for an explanation of Plato’s theory of how Timocracy (a government based on honor) leads to Oligarchy (a government based on wealth and power) leads to Democracy (a government based on liberty and equality) leads to Tyranny (a despotic authoritarian state devoid of liberty) in a Republic. On that page we also discuss Plato’s theory of the ideal class structure, and his theory that only Monarchy and Aristocracy can avoid the above decent of the forms (or more specifically, how Plato’s Kallipolis AKA “beautiful city”, which is very similar to Aristotle’s Polity AKA “ideal city”, which in both cases is roughly a mixed Republic like the U.S. which is part democracy, part oligarchy, part aristocracy, can ensure this).

Notes on How to Understand the Forms of Government

Whenever someone tells you the forms, they are translating a few different ancient Greek works, typically mashing them up with modern understandings, and then presenting a theory. Then, even the most famous philosophers from Locke to Rousseau differ a bit on how they present the forms.

Given the inconsistency over time, it’ll be helpful to understand the following notes in the following sections:

Notes on Understanding “Aristocracy“, “Republics” and “Republicanism“

First off, Aristocracy is a classical form of government and a Republic is a lawful sovereign state in which a sovereign people are represented by representatives.

The two terms are nearly interchangeable under some conditions, but have different meanings under others. On this page we generally equate “republic” with “aristocracy”, denoting it as a form of government, and America’s founders typically used Republic this way as well (the Republican party name even denotes this interpretation)… but things are a little more nuanced than that.

A republic is very roughly 1. a Constitutional 2. organized state 3. in which power resides in representatives… this means a Republic can technically, under loose definitions, be a monarchy, an aristocracy, a democracy, or a mixed government, officials can be elected or not, it can use federal power or be a confederation, etc. As long as the nation upholds a constitution and has representatives of the people, the term “republic” works.

In this sense, “Republic” is a term that loosely just means “a lawful state”, more than being “a fundamental type of government” (and this is proper usage, not usage in practice by a given state like the awkwardly named “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea” .

That said, Republicanism has a more specific meaning, it specifically speaks to the favoring a Republic over a pure Democracy or pure Monarchy, it is a call for a state in which people, not kings, hold popular sovereignty (why the U.K. and America’s founders and Machiavelli fought for it). Thus, in the types of government, when we say “Republic” we are saying lawful citizen driven Aristocracy and not a principality (as Machiavelli would have defined “republic”). We use the term like this to show that when we say the U.S. is a Republic, we mean it is a “mixed government” rooted in an Aristocracy, in which the people are sovereign.

We could say “a Republic is a state without a monarch”… but, I don’t think we should define it so strictly, as the U.K. is a Mixed Republic in just about every sense, and they have a Monarch (sure, we can call this a Constitutional Monarchy… but for me it isn’t “not a Republic”).

So simple as possible, 1. A Republic is a lawful state where the people have sovereignty and representatives rule 2. Aristocracy is the proper name for the form of government. 3. Republicanism in the original sense denotes one who favors a liberal Republic 4. Republican in the modern sense is essentially unrelated.

TIP: For more reading, see “what is a Republic?”

Notes on Plato and Aristotle’s Forms

Since the Greeks didn’t fully agree, since Aristotle came after his teacher Plato, and since we typically use Aristotle’s work (not Plato’s) as a modern foundation, it is important to grasp the following points.

THE IDEAL STATE, SOUL, and PERSON: The Greeks weren’t just talking about “governments” in their theories, they were talking about the nature of justice in relation to the ideal state, soul, and person. They were talking about Hume’s fork, the greatest happiness theory, all of metaphysics, and social science. Souls form men, men form states. The state, being a representative of the perfect person and soul is discussed as such. Their’s is a real theory of governments, but it is meant to be equated to the general concept of arete (the highest good). A perfect soul, structured like the perfect state, creates the perfect people, creates the perfect state, when the perfect state, spirit of the laws, and class system foster this. None of this can or should be separated, although the key is separating the powers. A state that promotes greed in all classes, they say, is bound for tyranny.

ARISTOTLE’S FORMS OF GOVERNMENT: Aristotle takes a different approach than Plato, and it is the same that will be taken by most philosophers as a foundation. It is simpler, so lets note it first. Aristotle, as shown in the modernized chart above, divides the forms by “who rules” and then discusses types. This whole theory can then be put in a chart like the one above to generally state that each form has a general correct and deviant form (each with different subtypes, for example Monarchy can be limited or absolute, but in both cases be correct). Thus, although a full reading of the Republic, Statesman, Politics, etc is in order, and second best is just a course on this or even some cliff notes, we can avoid all that just grasping Aristotle’s forms as presented in the chart above. Later philosophers will pull from Plato and Aristotle and add in their own thoughts, but Aristotle’s forms are a very workable foundation that will hold up in any time and in any era.

PLATO’S FORMS OF GOVERNMENT: Unlike Aristotle, Plato separates governments by not only who rules, but by virtues. For Plato, Monarchy and Aristocracy are the only two correct / lawful forms (outside the perfect mixed form), and all of the aforementioned (democracy / anarchy, oligarchy, and tyranny) are all deviant / corrupt. Here Plato considers democracy and anarchy as a single form, and he adds in a timocracy based on honor as yet another corrupt system (a corruption of the aristocracy with an “inferior” political class and military AKA “inferior” guardians and auxiliaries in Plato’s terms). For Plato, only Monarchy and Aristocracy, which he considered the same form for most purposes, were not corrupt because they were the only forms that had the authority, virtues, and culture that could ensure the perfect class structure and state-virtues.

THE POLITY OR KALLIPOLIS: One should note that Aristotle calls the perfect Republic a “Polity”, which sort of tautologically means “the ideal city state”, but also means a constitutional law abiding government that mixes aristocracy, oligarchy, and democracy (essentially a “Mixed Republic”). Here we can generally say Aristotle and Plato agree that this Polity / Republic form is best (and this is, on paper, what America is; very much on purpose of course). The only really difference is that Plato calls it a Kallipolis. With that said, “polity” or “kallipolis”, isn’t just a form, it is “the concept of the best form” (the form that best fosters a utilitarian theory of justice), the ideal state that is the subject of Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’ Politics.

PLATO’S CLASS SYSTEM: In his Republic, Plato doesn’t just muse on “the perfect city-state” (the ends of discussing the virtues of government, the forms, and the nature of justice; the point of the Republic) he also muses on the perfect structure of classes which the government governs and ensures. Here he says there should be a producer class, an artist (luxury class) which is part of the “producer class”, a class of warriors AKA an “auxiliary class”, and a class of philosopher kings AKA a political “guardian” class. Each class had its own virtues, was specialized, fit with a natural type of human (so no one would forced to be something they weren’t) and could only keep in balance if they kept to their virtues. They key to Plato’s theory, not Aristotle’s, is realizing he puts the emphasis on this and thus he sees only Monarchy and Aristocracy as good forms and does not care as much about “who rules”. For Plato, an Oligarchy is almost worst than democracy, because at least an oligarchy has the laws, manners, and restraints of an aristocracy.

NOTE: The philosopher king is not the philosopher of Plato’s day, or the one we know today. It isn’t a snooty academic, it isn’t just someone who is book smart, it is the arete of a philosopher, one trained from birth in the art (with also a natural inclination). It is a mythical idea that can only be realized in a carefully structured perfect state. Why have classes? Well, this allows producers to love money, warriors to love honor, artists to love art, and leaves the wise philosopher (who knows all but loves only truth) to rule. So then, if you are driven by money and pleasure, then your innate character has chosen your class. This is a type of communism, a planned state, but only loosely, as the idea is to give all types maximum liberty via specialization based on their natural selves. Needless to say this is a utopian system never tried in practice. Since it is Utopian, the Greeks concede that in general a Monarchy or Republic is best, for while not perfect, it gets the rule of law right, and that keep properly breed the virtues of the state.

A Note on the Types of Democracies

Before moving on, it’s important to note that each form has many types that can be derived from it, or derived from mixing it with another type. For instance, Representative Democracies (AKA Republics or Parliaments ruled by officials and law; where the many give power to the few via vote and constitution) are a hybrid of Aristocracy (ruled by the few, by law) and Direct Democracy (everyone votes directly on laws). Thus, speaking in terms of the above chart, they can be placed in either the few box or the many boxes (on the correct side). In classical terms “democracy” means “direct democracy,” in practice it can describe a wide range of governments.[12][13]

IMPORTANT: Because democracy comes in many forms, it is treated different by each philosopher. If you read Plato, he equates it with anarchy and describes it like a mix of anarchy and communism (a utopian version destined for collapse into tyranny). If you read Rousseau he treats it as virtuous, montesquie suggests mixing it in but thinks it is in a fault in a pure form. It is probably the most contested of the forms. Beware of making overly general conclusions like “democracy doesn’t work”. Democracy is great, it just has dangers of being excessively equal or excessively liberal. Liberty and equality are virtues, the danger philosophers realized is in excess.

Who Rules? (Types of Government). A take on the forms of government. There is more than one way to explain the forms, but we can always revert to Aristotle and Hobbes for simple answers. This chart, as is common, places representative democracies under “the many” (we place it under the few, since the many give power to the few, and the few rule with the consent of the many). Likewise, they call anarchy “no one,” this is mostly semantics. I prefer the table we present, but this video is otherwise good.What is the Difference Between Aristocracy and Republic?

Both aristocracy and republic imply “rule by the few”, but republic implies an organized law abiding government of representatives and different positions, while the term aristocracy implies a small privileged class or rulers. If a few barons controlled a country, or if the king delegated power to a few elite, we might call them an aristocracy. In a country like America where we elected officials to represent us in government, we call it a Republic. That said, many from Aristotle to Hobbes treat aristocracy and republic as similar or even “same” correct forms of government or use the words interchangeably, and this is why we have chosen to do so as well.

TIP: Modern depictions of aristocracy tend to regard it not as the ancient Greek concept of rule by the best, but more as a plutocracy—rule by the rich…. I get if this is confusing, but remember, the model presented above is based on the Greek model.[14]

What are Tyranny and Despotism?

As we noted above and explain below, tyranny is putting a specific will before the general will, or rather, putting the interest of the ruler(s) before the law (as explained by Locke, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and others… but not agreed on by Hobbes, Filmer, and others).

Meanwhile despotism describes absolute power of the one. Thus a good King who follows the laws is a monarch, and an evil dictator who puts themselves before the law is a despotic tyrant. Any type of government can be described as tyrannical when it becomes corrupt and puts specific wills before the general will and the law (in other words, when it purposefully violates the social compact without consent in its own self interest).

TIP: According to Plato, when democracy and oligarchy breed too much vice in a state, the state collapse into a tyrannical state. This is why Buchanan criticizes both democracy (the form with many heads) in his dialogue “the Powers of the Crown” in which he also criticizes tyranny.

On the grounds that the law was desired to keep the king within bounds, not the king the law. And it is by virtue of the law that he is a king; for without it, he is a tyrant. – George Buchanan 1579

TIP: A King who has absolute power or acts as a despot isn’t necessarily “corrupt”. In the Roman Republic the law allowed for temporary despotism in times of crisis, this was within the law, and thus was not deviant. However, Hitler was a corrupt tyrant, as even though he ruled by the law, the law was changed to fit his needs, and this is “corrupt”.

TIP: When the rulers are bound by the law, and rule from within the law, the government is “correct”. If the governors do not rule from within the law, this is tyranny / despotism (classically speaking of course). See Aristotle’s Political Theory. If you think a King is above the law, then this is fine, by Aristotle, Machiavelli, Buchanan, Locke, Rousseau, Mill, etc disagree. On the plus, Hobbes agrees with you and says there is only three forms.

Basing the Forms on Other Factors

Before moving on, we should also note that while the classical forms have been well defined since Aristotle, the complex forms listed below can be based on many factors. Government types based on economic policy are common in practice (a Communist state for example) and other aspects of government like how the branches are structured (is there a separation of powers?) and if it is a single nation or union of states (like the U.S.) add complexity.

Non-Western Forms of Government

We can draw political philosophy from the Chinese (legalist vs. Taoist), Native North Americans with their Confederate Iroquois, Indians with their caste system, and Middle-Easterners like the philosophers of the Golden Age of Islam such as al-Khwarizmi.

Aquinas’, Machiavelli’s, and Buchanan’s Political Theories

The next key western philosopher who discuss politics, in chronological order, are Saint Thomas Aquinas in the 1200’s followed by the father of political science, Machiavelli and then by the very influential, but sometimes forgotten, George Buchanan. So let’s touch on each of them briefly so you can understand how the core theory of government evolves over time.

Cicero and Livy, as thinkers of the late Roman Republic both laid much of the groundwork of modern political philosophy, by talking about their Rome and Greek philosophy they helped to popularize the concept of a Republic and the virtues of the Republic.

St. Thomas Aquinas agrees with the Greeks, but poses the questions underlying the foundation of the forms of government as “how the regime is ruled” and “whether or not it is ruled justly” (that is, for the common good and in line with what we would today call The General Will). He had great respect for Aristotle whom he called “the philosopher” and based his theories on the Greeks, as do many later philosophers. Learn more about Thomas Aquinas: Political Philosophy.

Later we get Machiavelli with his early 1500’s work the Prince and Discourses on Livy where (in Livy) he states the six forms of Aristotle in Livy (i.e. he denotes the three correct forms monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, and three incorrect forms tyranny, oligarchy, and anarchy) and expresses a preference for a free republic over a hereditary Principality in his Prince (a hereditary monarchy). He also provides early comments on the state of nature, the dangers of majority rule, and offers an opinion on Solon’s Athens and the Roman Republic. To Machiavelli, there is only a principality (hereditary or not) or republic (trading or not).

The debate between Monarchy, Tyranny, and popular governments can be gathered from reading three works. First, King James I‘s 1597-98 works The True Law of Free Monarchies (or, The Reciprocal and Mutual Duty Betwixt a Free King and His Natural Subjects). Second, Basilikon Doron (His Majesties Instrvctions To His Dearest Sonne, Henry the Prince). Third, George Buchanan’s 1579 work De jure regni apud Scotos (The Powers of the Crown in Scotland; or, A dialogue concerning the due privilege of government in the kingdom of Scotland). In these works James coins the concept of the Divine Right of Kings and expresses a preference for a free Monarchy, while his one-time tutor Buchanan says Tyrants can be overthrown justly, as the source of power is the people not the Divine Right of Kings.

Montesquieu’s Forms of Government, and the Spirit of the Laws

Montesquieu agreed with Aristotle on the forms of government, although he uses the terms aristocracy, republic, and democracy carefully, often referring to mixed governments (and should thus be read carefully).

Unlike Aristotle however, Montesquieu said the distinction between correct and deviant forms was not solely a matter of virtue alone, but a matter of law (where the point of laws, or spirit of the laws, is to embody the virtue of the state; in words, it IS about virtue, but virtue as represented by the laws).

More specifically, it is a matter of honor for monarchies, a matter of fear for despotic governments, a matter of moderation for republics, and a matter of equality for democracies. The exact virtues differ between pure democracies, types of aristocracies, trading republics, non-trading republics, types of mixed governments, etc.; it’s a whole theory, you can read about it here.[15][16]

Montesquieu points out that moderation and modesty are key virtues in a trading republics, which are like most Western powers today. People are necessarily unequal but use moderation and modesty to avoid inciting jealousy, which would dampen the love of the republic for the have-nots. Likewise, social mobility through the classes is vital for the same reason.

Meanwhile, in a socialist state like Sparta where male Spartans were equal to each other in wealth and political power and had what Montesquieu calls “pure democracy,” equality is the highest virtue. If the people don’t love their equality of both rights and things, the state cannot subsist in this form.

In both instances, the love of these qualities and a reflection of these qualities in education, culture, and vitally the laws is what ensures a form of government. It is what keeps “correct governments behaving correctly” and what makes governments correct in the first place.

I can’t fully relate all the complex ideas of Montesquieu here, but consider these quotes (including his empirical take on virtue in a republic):

VIRTUE in a republic is a most simple thing; it is a love of the republic; it is a sensation, and not a consequence of acquired knowledge; a sensation that may be felt by the meanest as well as by the highest person in the state.

A love of the republic, in a democracy, is a love of the democracy; as the latter is that of equality.

IF the people are virtuous in an aristocracy, they enjoy very near the same happiness as in a popular government, and the state grows powerful. But, as a great share of virtue is very rare where men’s fortunes are so unequal, the laws must tend as much as possible to infuse a spirit of moderation, and endeavour to re-establish that equality which was necessarily removed by the constitution.

The spirit of moderation is what we call virtue in an aristocracy; it supplies the place of the spirit of equality in a popular state.

Though experiment: What is a tyrant but one who puts themselves before the law, what is oligarch or plutocrat but one who puts special interests before the law, what is anarchy but that which is lawless? See Baron de Montesquieu, The Spirit of Laws (1748).

TIP: Montesquieu’s real name is Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu. He was one of the most cited authors in America around the time of the revolution and was one of James Madison’s biggest inspirations.

TIP: Montesquieu describes the government types noted by the Greeks, but focuses on governments that work in practice which he says are Monarchies, Despotic governments, Republics, and popular governments (Democracies).

TIP: Rousseau also noted that the deviant types put power before the law in a chapter called “How government is abused. Its tendency to degenerate.” Rousseau had clearly read Montesquieu; each later philosopher has read the work of his or her predecessors.

Hobbes’ Forms of Government

Hobbes saw it like this:

- One: Monarchy

- Few: Aristocracy

- Many: Democracy

Hobbes, perhaps even more correctly than Montesquieu, states that tyranny, oligarchy, and anarchy are just words we use when we don’t like something. They aren’t different forms of government. See Thomas Hobbes Leviathan.[17]

TIP: Robert Filmer offers a similar view as Hobbes, but argues for the Divine Right of Kings, a peculiar concept in an otherwise insightful book. John Locke counters the theories of both Filmer and Hobbes. Locke specifically defines forms like Hobbes Monarchy, Aristocracy, and Democracy and plays on Buchanan’s ideas of the power residing with the people, the right to consent, and the right to overthrow tyrants. Likewise, Filmer and Hobbes take James I’s stance advocating for absolute monarchy. See Social Contract theory for this related discussion.

An illustration of the basic forms of government. Hobbes’ imagery re-worked to show the forms, the body politic, the head(s) of state, and the arms of the executive (wand) and legislative (sword). When there is discord between the body, head, and arms we get factions.

You know the proverb, “the people is a monster of many heads.” You are sensible, undoubtedly, of their great rashness and great inconstancy. – Buchanan, expressing the Greeks distrust of mob rule.

Rousseau’s Forms of Government

Rousseau saw it like this:

In one sense, there is only the Republic (Book 1 Chapter 6 of the Social Contract). In practice the will of the people can’t be different than the will of the state. The people are the state, a monarch has to delegate, and democracies form factions, so they always err toward a Republic in practice.

Despite his stance, Rousseau admits that, in practice, there are the three forms in chapters tellingly titled Democracy, Aristocracy, and Monarchy. Different power structures are needed for different states and cultures, and to create unions between different types of states and cultures. For example, Rousseau says that having fewer rulers works better in larger states. Rousseau, like Montesquieu, believed that no single form government was best suited for all countries due to differences in climate, culture, technology, and land. Mixed governments were a wise combination of the classic forms, as were a separation of legislative, judicial, and executive powers.

Later in the book, Rousseau clarifies that: Strictly speaking, there’s no such thing as a simple ·or unmixed· government. So we can say, that even though Rousseau recognized the classical forms, he saw all governments as types of mixed Republics and all states as requiring unique mixes. (Book 3 Chapter 7 of the Social Contract) See Rousseau’s social contract theory see the excerpt from Montesquieu: The Spirit of the Laws, 1748.

Rousseau specifically rejects Deputies or Representatives, as a chapter with just such a title clearly slams the governmental style which has elected officials voting on laws rather than the people. He goes as far as to call Britain, and by extension today Americans, slaves. Rousseau favors mixed governments in practice but is calling for social democracy.

TIP: As noted above, Machiavelli also strongly favored a Republic. In the Prince, he dismisses the idea of Democracy, since one has never really existed as a successful state, and (if you read the book as satire and along with Livy, as it arguably should be) makes it clear as day that he thinks a free Republic trumps a Hereditary Principality.

Hume’s Forms of Government

Hume saw it like this:

The three forms exist, but the best form in practice is a mixed government, specifically a Constitutional Parliamentary Monarchy.

We can see this in Rome, where before Caesar the Government was a Democratic Republic and both its Democracy and Senate failed it to the point where people embraced the rule of their first Caesar.

Rome aside, take Britain as another example. Britain mixes Monarchy with a Republic. Thus it avoids the tyranny of the majority in terms of having to elect a Monarchical type figure like a President, but also avoids despotism and tyranny as the law of the Republic keeps Monarchy in check. Because of this, the people enjoy personal liberties, such as freedom of the press, unlike anywhere on earth. This was true, according to him, in 1758 when he claimed this in ESSAY II. Of the Liberty of the Press. from Essays and treatises on several subjects… although you’ll note above Rousseau disagrees.

Hume’s call for a mixed government was published in 1777, meaning like all other texts mentioned here (minus Marx), America’s founders would have had access to it when discussing the Constitution.[18]

Burke’s Forms of Government

Burke agrees with Hume. He supported the American Revolution but was very critical of the more radically liberal and Democratic French Revolution. Burke favors a mixed government that sticks with tradition. Tradition says a hierarchy power structure, order, and the rule of law ensure liberty; total natural liberty ensures nothing by anarchy. See Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents (1770), and for his best-known work, Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790).

TIP: The above list is not an exhaustive conversation on the basic forms of government, but it does offer a range of opinions.

Marx’s and Engels’ Forms of Government Compared to Smith’s – SocioEconomic Government Types

Marx and Engels, are the fathers of Communism, Adam Smith is the father of Capitalism, post-1776 it was realized correctly that economics was such a large factor in government that we could define government types by their economic system. All these philosophers were empiricists like John Locke, but instead of focusing on “the law,” they focused on “the economy.”

Smith wrote that Free Trade is a natural system and Capitalism is the economic system that works best with man’s natural self-interest, his moral sentiment. The invisible hand is the government, the hand behind the sum of all wills-in-action. Like the Greeks, Smith focused on the concept of specialization, unlike the Greeks, he believed individual choice would lead to a type of practical utopia (the concept of the free-market).

Marx and Engels, playing off of Hegel, divide governments born from economics and technology into five historical social stages: Primitive communism or tribal society (a prehistoric stage), ancient society, feudalism, capitalism, and lastly their utopian Communism. See Marx’s theory of history. Their Greek inspired cycles aside (no different than Plato’s Regimes really), they also worked with a class theory (like the Greeks) to create a very telling and smart theory that is often cast aside with the Communist bathwater. In ways the silliest thing modern society has done, aside from abandon the importance of spirituality along with the importance of the separation of church and state (no, they are not the same, one is a fundamental aspect of the human condition, the other is religion), is to have overly politicized Marx. He was one of the greatest thinkers of his century. One should note that his predictions came true, and that he essentially gets a scarlet letter for suggesting an overly equal system and revolution (which turned out poorly, but again, we throw out the baby Marx with the bathwater and thus we will be doomed to not learn the other lessons he tried to teach us).

TIP: People are driven by a few things: self-interest (moral sentiment), spirituality, passions, tastes, desires, incentive. Sure, a utopian commune is equal on paper, but it is superficially equal, removes incentive, and consequently limits liberty and right. These are paradoxical effects common with complex social systems. See liberty and equality and wealth inequality for more discussion.

“In adopting a republican form of government. I not only took it as a man does his wife, for better for worse, but what few men do with their wives. I took it knowing all its bad qualities.” The worst of these, in his view, was the tendency of republics to degenerate into “Democracy, that disease of which all Republics have perished, except those which have been overturned by foreign force.” – The Political Thought of America’s founding father Gouverneur Morris expressing a preference for a free republic.[19]

…while the law [of individualism, competition, and capitalism] may be sometimes hard for the individual, it is best for the [human] race, because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department… The Socialist or Anarchist who seeks to overturn present conditions is to be regarded as attacking the foundation upon which civilization itself rests, for civilization took its start from the day that the capable, industrious workman said to his incompetent and lazy fellow, “If thou dost net sow, thou shalt net reap,” and thus ended primitive Communism by separating the drones from the bees…. Not evil, but good, has come to the race from the accumulation of wealth by those who have the ability and energy that produce it. – Andrew Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth

Modern Forms of Government (Complex Power Sources)

Here are all the common and uncommon forms of government in practice, this is sort of an exampled list of the list above. Remember mixed-governments can mix the forms below creating unique solutions for each state:

NOTE: Some terms like dictatorship, autocracy, despotism, totalitarianism, and tyranny have very similar meanings and are sometimes used interchangeably by different authors and eras. We will attempt to provide their current accepted meanings.

- Monarchy: Includes an Absolute Monarchy: Absolute power granted to one, typically a hereditary King or Queen who was given power by Divine Right, granted it by God or given Absolute Right by the people. Also, it includes a Constitutional Monarchy: typically implying a monarch without absolute power who rules by law like in the U.K. Constitutional Monarchy is one of the most common government types historically. In modern governments, it almost always contains a Republican sub-system like a parliament.

- Dictatorship: An authoritative government that denotes a highly regulated population where life is dictated. It is typically run by a single ruler “a dictator,” but not always. Typically not gained through hereditary means. Almost always a Military Dictatorship or Military junta, but sometimes includes an elected despot like Hitler. Dictatorship is a very common government type following wars and revolutions. A dictator comes in and restores “order.” Dictators usually usurp the law and become tyrannical, but technically a dictator can be benevolent and in this case is essentially an absolute monarch. Rousseau, for instance, suggests a dictator is useful in times of crisis for a limited timespan if it is done in the General Interest.In his vision, this could be like times in Rome, but never like Hitler and the Fire Decree story. A dictator who usurps the law for anything but the common good is a tyranny. Totalitarianism doesn’t denote being bad; it denotes absolute rule.

- Autocracy (Authoritarianism): A strong central power in the hands of a single person. Can have self-imposed limits on government (but not external). An angry lynch mob is an authoritarian entity, so is a tyrant. Authoritarianism doesn’t denote being bad; it denotes absolute rule.

- Despotism: Describes absolute power, but can be in the hands of an individual, the few, or many. Despotism doesn’t denote being bad, it denotes absolute rule.

- Totalitarianism: Very similar to despotism. It differs on in that it denotes no limits on government, “total”-itarianism while a despot may still abide by laws and customs. Totalitarianism doesn’t denote being bad; it denotes absolute rule.

- Tyranny: Any deviant form of government is tyrannical. Tyranny means putting the law before the people. It classically describes a tyrannical despotic monarchy, but it doesn’t have to be a single ruler. When the many act as a tyrant, like with a lynch mob, it is “tyranny of the majority.” Only roughly distinguished from a dictator. Tyranny does denote being bad; it is one of the few forms that is always bad.

- Fascism: An authoritative government focused on sameness and exclusion, almost always necessarily authoritarian. Hitler and Mussolini were fascists, because they demanded sameness from the in-group and excluded an out-group. It is different than Communism (even though communism demands sameness too), because Communism is an economic system, and it demands inclusion.

- Oligarchy: A country run by individuals who come to power through wealth. Plutocracies and corporatocracies are types of oligarchies. For Plato, Oligarchy was less orderly than Timocracy and collapsed into democracy via a Revolution.

- Plutocracy: A form very similar to oligarchy in meaning. A country or society governed by the wealthy. This is the most common form of government outside of nations run by Churches and kings.

- Corporatocracy: A country run by corporations. There has never been an official corporatocracy, but some accuse America of possessing aspects of an oligarchical corporatocracy.

- Theocracy: A government ruled by a Deity or in practical terms ruled by Church and religion. A common form of government, but is typically run like a monarchy or is only part of the overarching system.

- Timocracy /Timacracy: A form of government where only landowners participate according to Aristotle, but better defined by plato as a nation based on honor and duty. For Plato, it was the best of the corruptible and unstable governments. It is analogous to Plato’s warrior class.

- Feudalism: The upper class (or military) rule and protect the lower classes. It is like a Timacracy, but often based on wealth (as mercenaries essentially rule, with the allegiance being to money over honor.)

- Technocracy: Government based on technology and science (obviously a theoretical government). Some companies may run their institutions like this, but mostly it happens in small groups. This can also be seen in a less glamorous light as the control of society or industry by an elite of technical experts. Like socialism the problem isn’t in the ideal; it is about the practical implications, namely revolving around the questions “says who?” and “According to what data?”

- Krytocracy or kritarchy: A government based on ethics, wisdom, knowledge, morality, and law. Similar to the Supreme Court, typically a subsystem and not an overarching system in practice. People tend to misunderstand this and confuse it with theocracy (it isn’t the same).

- Aristocracy: Ruled by the few. Individuals who come to power through appointment (either by heredity, vote, or appointment by a higher class).

- Republic: A hybrid Aristocracy and Democracy. Can be elected or not, but officials are typically elected. Denotes being ruled by law. Also called “parliamentary” (where parties gain seats in parliament and form coalitions). Many of our forefathers thought a Republic was best due to it being a lawful middle ground form of government.

- Polity or Kallipolis: An ideal government; can be thought of as a mixed government with a separation of powers. It is the Greek term for “ideal city state”. So, if we pull from all the above philosophers, we can define this ideal state as a mix of their ideals.

- Democracy: Refers to direct democracy where everyone participates and comes in many forms but is either direct or representative. Pure direct democracy is historically rare as an overarching system, but boards of companies and other subsystems use it all the time.

- Demarchy or Sortition: Democracy by lottery in the case of Demarchy or just government by lottery by sortition. Athens had this form of government.

- Communist state: A state that embraces Communism in any form, here not specifically being a statement on economics. A Communist state is almost always run like fascist dictatorship in practice, which gives Communism part of its bad name. The other part is its absolutist rejection capitalism. Marxism is supposed to be a commune-style government like a modern version of tribalism, without a despotic central authority, that embraces a perfect equality, especially for the workers. The problem is that starting the system requires a worker’s revolution, and this type of anarchy always leads to despots if the society is not advanced enough, and a bit lucky. Revolution worked for Britain and America but was often not so great for other countries. Rousseau didn’t go as far as Marx, but he did note correctly that communes work in small groups only, or as subsystems. It worth noting that Rousseau’s concept of the General Will incited another type of populous rebellion, the French Revolution, so it isn’t only Marxism that gets ugly in practice. We won’t further confuse the issue here since there is no true Marxist state, and only forms like Stalinist-Leninist-Marxism seem to exist in practice. That which is faulted in theory has become somewhat of a boogyman in practice. See our page on Communism vs. Fascism for our take on these similar and prickly social systems.

- Primitive “Tribal” Communism: Another system that only exists in small groups is primitive communism, it is a small tribe-like commune (as would be found in the transition into the Neolithic revolution). Marx thought his form of Communism was the next step; Carnegie was more skeptical.

- Anarchism: No rules. Can be collective anarchism (no rules, but work together) or individual anarchism (no rules, don’t work together). Gangs are essentially a type of mix between communes, anarchy, and feudalism.

- Anarcho-capitalism: No state, but rules based on classic liberalism. This could also be called a “Capitalist State.” It’s almost always a subsystem in practice. Can range from “eliminating the state” in favor of liberty individual sovereignty, private property, and free markets, to various degrees of concession up until it becomes a more centered classical liberal early American-like government.

TIP: If you want to verify the accuracy of the above statements, see the CIA world fact book. We cover every basic government type listed, plus other common forms used to describe governments in practice, this means we have covered all real (and even some theoretical) basic forms of government. Thus, all governments can essentially be described using the terminology on this page.

Hybrid Forms and Mixed Governments

Any of the above forms can be mixed to create a hybrid. For instance, England has a parliamentary constitutional monarchy. The major social liberal western democracies almost all exclusively use separation of powers to create a hybrid of basic government types.

In general terms, Rome and Athens were mixed-Republics like most modern western powers (Athens erred on the side of Democracy, Rome a Republic and then a Monarchy).

TIP: For a more expansive list see Forms of Government by phrontistery.info. This list isn’t practical, but it is the most overly complete list I’ve ever seen. This List of forms of government from Rational Wiki is a little more usable.

Forms of Government (Power Structure)

The above primarily describes power source, not a power structure, economic system, or other factors.

For Power structure (not source) There is:

- Separatism: Small decentralized power, no nation.

- Federalism: United under a strong or weak government within a nation. Including Confederacy (today typically meaning a weak central government) and Federation (implying a strong central government; either with less, equal, or more power than states… today typically implying more power).

- Unionism: Expansive across nations (or states). This can lead to non-self-governing states but doesn’t denote a lack of sovereignty. The U.S. is a hybrid of Federalism and Unionism, a Federation of states in a Union under a central government.

The Government is also either:

- Constitutional or UnConstitutional

- Presidential (with an elected or unelected Monarch-like figure), semi-presidential (a president exists along with a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter two being responsible to the legislature of a state), or Parliamentary (run by a legislative body, Congress is a type of parliament). Thus, we can make the one, few, many distinctions with rulers of any branch as well!

Leaders are either:

- Elected or Unelected.

Branches of Government are commonly divided in these ways (i.e. a separation of powers):

- Bipartite: Two branches (typically executive and legislative)

- Tripartite: Three branches (typically executive, legislative, judicial)

- Unicameral: A Branch ruled by a single entity.

- Bicameral: A branch divided into two parts.

- That language is typically used when referring to dividing a legislature.

And then the government holds an ideology per issue including economics and social issues.

- For economics, for example, this can any form of capitalism or socialism (including Communism). See social market vs. free market.

- A nation can also be conservative, moderate, liberal, or progressive on any issue (including trade and military).

- The country can also be nativist or globalist.

- In overly simple terms, a nation can be “left or right” on a wide range of issues meaning it is authoritative or not, idealistic or not, social or not, etc. See our page on left-right for a broader discussion on the breadth of this concept.

TIP: Any system can have so much weight in a society it can become the dominant system. Rome was imperialist to such an extent it was a facet of its character. China is “Communist Republic” the U.S. is a “Capitalist Federal Republic.” Etc. Most nations have an official title, but it isn’t always their true form.

NOTE: To clarify the above. Socialism, Communism, and Capitalism aren’t forms of government strictly speaking, they are economic systems. Although some “communist states” exist in practice, they are rarely actually decentralized communes. Even though America is Capitalist, that is an economic ideology and not technically a comment on its power structure or power source. Terms like Federalism or Confederacy aren’t specifically forms of government either. Forms of government generally describe a nation’s “power source,” not other aspects of the government. The form doesn’t describe power-structure (like Federal), how that power is granted (Constitutional), or the countries economic system or social policy (like Capitalism, Social Market, or Communism). Consider The United States is a Constitutional Federal Republic; with Strong Democratic values (a federation of states with a Representative Democracy, ensured by a constitution, that values democracy and liberty). The three classical forms are the only basic forms of government. Everything else is just a way of adding depth and complexity to the discussion.

So, What is the Best Form of Government?

Putting together all of the above, we can conclude only one thing.

None of the above forms is “the best form of government”.

That said, Plato, Aristotle, Machiavelli, Montesquieu, Locke, Rousseau, Jefferson, Madison, and other thinkers give us a darn good answer in eluding that, “a constitutional mixed system that embraces aspects of democracy and aristocracy is best”.

Mixed, because of its checks and balances and flexibility, and constitutional because it is the rule of law that ensures liberty and rights.

With that said, a better tactic than looking at “the best form” is looking at factors like the ends of the form and that means looking for signs of a good government and signs of a bad government.

A good government is one where people are happiest, leaders virtuous, liberties and rights plentiful, the state strong, technological output high, the people educated, and the law aligns with the general will (not popular consensus or special interest) but every culture, people, and region is different. Hence, the importance of sovereign states and nations, federalism, and binding laws like human rights documents, international treaties, constitutions, international courts, supreme courts, the U.K., the U.S., the E.U., the U.N., etc.

Meanwhile, a bad government is one that ignores pitfalls. For instance, we have long known the dangers of Pure Democracy, yet for some reason, we have many fans of pure Communism and Pure Anarco-Capitalism within our 7.2 billion?! A bad government is a government where people are unhappy, un-incentivized, hungry, uneducated, their liberties restricted, unproductive, not creating art and enlightened works, where superstition trumps reason, and where the rule of law is not just.

With the above said, sadly, we can also say its a bad sign when people don’t care enough about their government to participate, they don’t think their vote affects anything, and they think the choices are “essentially the same.”

I say “sadly” as the U.S. has about a 40% turnout for mid-terms. Rousseau is much less polite about this in his chapter on the signs of a good government. I won’t quote him here, nor is his word gospel.

Many of the political philosophers argue for erring on the side of liberty and democracy but not anarchy. They almost all swear by law and republics, especially mixed-republics, and nearly all favor a constitution and decry tyrants and oligarchs. A few express a preference for free-monarchies or even in specific situations despots, although rarely tyrants).

Thus, to combine all the wisdom of the giants, the best form is the form which is “the most just” and “fosters the greatest happiness” with “the least pain” and otherwise the most “equality and liberty possible”. There is always a give and take… but that is why the key is generally the virtue of moderation (AKA balance).

Still, all thoughts aside, I can’t help but return to Rousseau who couldn’t help but return to Montesquieu to say:

“Liberty isn’t a fruit of every climate, so it isn’t within the reach of every people.” – Rousseau paraphrasing Montesquieu. They both speak of “climate” literally, and while this has merit, climate as a broader concept it makes far more sense.

With the above interpretation, this quote is a way of saying that each state (sub-state, sub-group, sub-region) needs a slightly different form government, a form best suited to its current needs and culture (why “federalism” and sub-systems” are important).

Thus, we can say, the best government largely depends on the culture and the times, and idealist systems like Communism and Anarco-Capitalism don’t magically work just because they may seem ideal on paper. The Romans knew there was a time for benevolent Despots and benevolent absolutists aren’t inherently bad, but that time should always limited by the law, lest we get a Hitler out of the fire panic.

Let’s end with a quote from Thomas Jefferson that reminds us that one of life’s truths is that we will never fully agree on what is best. All free nations contain political parties as an affect of human nature and liberty, and thus perhaps, we can say only, “a nation that values human life and liberty is best, but not every people best accomplish this in the same way.”

“Men have differed in opinion and been divided into parties by these opinions from the first origin of societies, and in all governments where they have been permitted freely to think and to speak. The same political parties which now agitate the U.S. have existed through all time. Whether the power of the people or that of the [aristocracy] should prevail were questions which kept the states of Greece and Rome in eternal convulsions, as they now schismatize every people whose minds and mouths are not shut up by the gag of a despot. And in fact the terms of Whig [liberal] and Tory [conservative] belong to natural as well as to civil history. They denote the temper and constitution of mind of different individuals.” —Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, 1813. ME 13:279 on politics as a naturally occurring system.

This is to say, the forms of government is an interesting conversation, but it is only one part of a larger conversation about naturally occurring social systems, social contracts, morality, and how many moving parts come together in balance to foster the virtues needed to ensure the ideal state. The ideal state is not one of pure equality or pure authority… but nor is it a state of pure liberty. Here, the highest virtue is balance, because it is balance that ensures justice, and it is justice that ensures the state.

- Politics. Aristotle

- “Plato’s Republic” classics.MIT.edu

- Category:Forms of government

- The Social Contract. Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Classic Forms of Government

- Types of Governments

- Aristotle’s Political Theory

- “Aristotle’s Political Theory” plato.Stanford.edu

- Aristotle Politics

- Plato’s Statesman

- Politics (Aristotle)

- Types of Governments

- FIELD LISTING :: GOVERNMENT TYPE

- Aristocracy

- 4.1 Forms of Government

- Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, Complete Works, vol. 1 (The Spirit of Laws) – 1748

- Thomas Hobbes Leviathan

- Hume Essays and treatises on several subjects

- The Political Thought of Gouverneur Morris