Patricians, Plebeians, Optimates, and Populares

The Roman Classes and Political Factions:

The Plebeians (lower-class), Patricians (higher-class), The Optimates (aristocratic political faction), and Populares (populist political faction)

The Optimates like Pompey (aristocrats) and Populares like Julius Caesar (populists) were two opposing political factions at the onset of the fall of the Roman Republic. Although both were Patricians (higher-classes), the populist Populares favored the “plebs” (commoners) and the oligarchical Optimates favored the patriarchal Patrician class.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

The class-warfare between the Patricians and Plebs, which saw struggles of both wealth and power, finally came to a head. The following political factions and figures were notable: Pompey, Cicero, and Cato the Younger (the Republican Patricians and Optimates) fought against Julius Caesar and Marc Antony (the Right-Wing Populist Populares who roused many Plebeians).

This led to the Ides of March (Caesar’s assassination of the 15th of March), the rise of Augustus, and the age of the Roman Empire.

Below we tell the story of the rise and fall of the Roman Republic by explaining the Plebeians (lower-class), Patricians (higher-class), The Optimates (aristocratic political faction), and Populares (populist political faction) and their roles in government and society.

“In a word, does the supreme power belong to you, or to the Roman people? Did the expulsion of the kings mean absolute ascendancy for you, or equal liberty for all?” Livy’s History of Rome: Book 4: The Growing Power of the Plebs[7]

FACT: America’s founders used to quote an often produced play in Revolutionary America called Cato, a Tragedy. It was about the assassination of Julius Caesar, and Patrick Henry’s “give me liberty or give me death“ line comes from it. The Anti-Federalist papers were signed by nom de plumes referencing the play’s characters, and the Federalist papers were signed by similar nom de plums as a response. Simply put, America’s founders were well aware of the struggles between Optimates and Populares, the fall of the republic, and the assassination of the Tyrant Julius Caesar. In early America, the Anti-Federalists are roughly the Populare faction and the Federalists roughly the Optimates (as the names imply), but Caesar being a liberal despot (and thus being representative of George III) was ideologically the enemy of all the patriot founders. Learn more about the Federalists and Anti-Federalists (the two factions the current Democrats and Republicans come from).

The Roman Empire. Or Republic. Or…Which Was It?: Crash Course World History #10.The Structure of the Roman Republic

We need a little background on Roman politics to understand the class struggles of the Roman Republic.

Rome went through several phases in its history. First, it had kings. Next, there was the Republic with a few different stages marked by struggles between the hierarchical classes. The Republic gave way to an age of emperors starting with Julius Caesar. Finally it “fell to the Gauls.” Rome changed, but never disappeared. It survived through the Crusades, to the Italian Maritime Republics, and today as Italy.

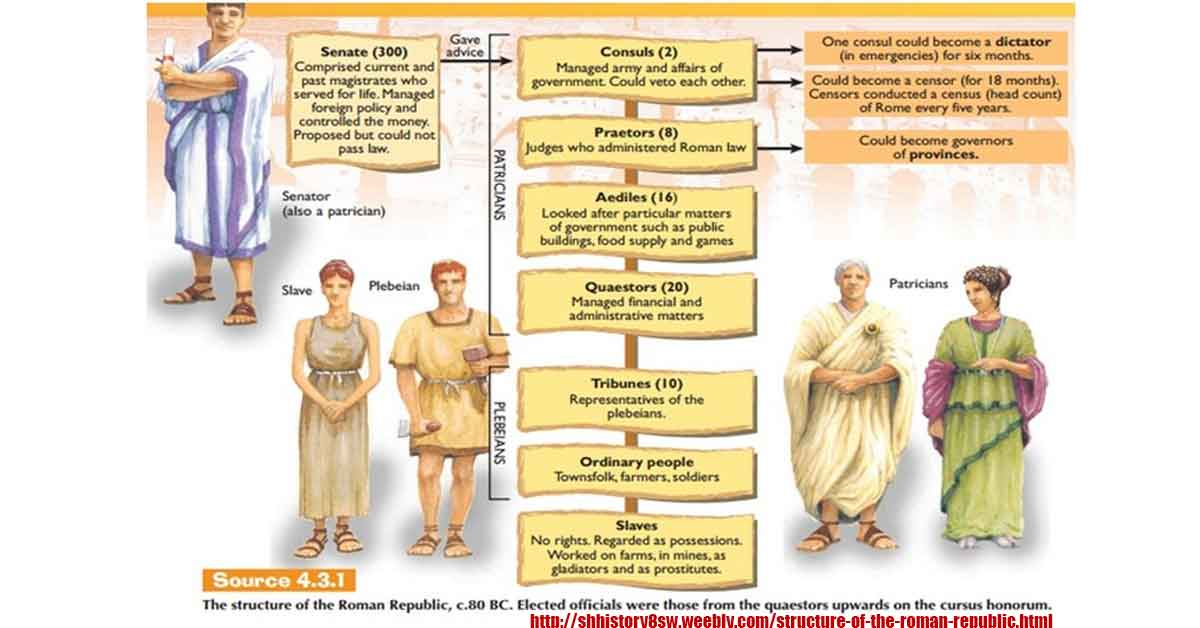

Of note on this page isn’t the ins-and-outs of Rome’s complex structure, which includes many tiers of elected positions that Patricians could fill, or an unelected and appointed oligarchical Senate with an advisory position, or a discussion on what “a Gaul” is. This page provides an examination of Rome’s two main classes and political factions at the time of the fall of the Republic. It is not intended as an examination of its Republican system of direct Democracy and checks and balances, or the positions of Senator, Consul, Praetor, Quaestor, Promagistrate, Aedile, Tribune, Censor, etc. These are discussed elsewhere.

The Roman Republic, which was initially structured in a military fashion with Centuries, was usually headed by two consuls or President-like figures who could take on emergency roles for a limited time. The Consuls were elected annually by the citizens and advised by a senate composed of appointed magistrates. Magistrates were unelected oligarchs and aristocrats appointed to their positions for life. Below these high positions were the equivalents of judges, treasurers, and censors who took the census. Below those positions was a tribune of the plebs instituted in 494 BC, after the first secession of the plebs, an unelected body with complex powers that ebbed and flowed, but at the best time served as a “check and balance” that could veto. While this isn’t all the aspects of government, it is enough for our discussion. For now, we will ignore the army, military tribunes, and others.

From the start of the Republic to well after its fall, the upper and lower classes fought in factions. These fights happened in government, between the tribune of the plebs and the unelected Senate in government and on the battlefield under names like Optimates and Populares.

TIP: See Erosion of the Plebeian tribunician power at the end of the Republic.

Political structure of the roman republic. Roman Republic – political structure (in a nutshell).TIP: The Roman Senate and Tribune of Plebs were a bit like the House of Lords and House of Commons in the U.K., or Senate and House in American. Of course, these later governing bodies were deliberately modeled on their Roman ancestors, as those governments are modeled after the Roman Republic, just as Rome drew from Athens.

The Struggle Between Patricians and Plebs

As noted above, the evolution of the Roman government was heavily influenced by the fight between the Plebeian class or “plebs” (commoners) and the Patrician class (the upper-class), both regarding the structure and in policy.

At first, after the fall of the first Kings, when Rome became a Republic, and then after the development of the Assembly of the Centuries from a military to a political body, the wealthier patricians became influential in elections. This resulted in legislation funneling power toward the upper-classes creating a corrupt and oligarchical government. However, over time, the plebs took back power, formed the”plebeian tribunes,” and even at points rose to positions in the aristocracy.

At times, even the lowest classes in this highly tired hierarchy took limited amounts of power. For instance, 135 – 71 BC saw the “Servile Wars” and Spartacus‘ slave rebellions during which the lowest classes rose up. There were also other Civil Wars which mirrored the battle between the members of the First Triumvirate Crassus, Pompey, and Julius Caesar).

Now that we have that background, the era of the Roman Republic 133 to 27 BC, which saw the factions the Patrician favoring Optimates (aristocrats) and the Pleb favoring Populares (populists), can be discussed.

ROME – RISE OF THE REPUBLIC.TIP: The political history of the Roman Republic is essentially a non-stop battle between Plebs and Patricians. It includes the story of the populist Gracchi, The Hortensian Law, the Plebiscites of 342 BC, and other struggles including those in the Patrician era (509–367 BC).

The Optimates Vs. Populares and the Fall of the Roman Republic

The Optimates (aristocrats) and Populares (populists) were both “elite” factions of patricians. Although the Populares tended to favor the Plebs, neither were from the lowly Pleb class. Rather, members on both sides were wealthy land owners, Senators, and Military leaders. Still, their name indicated their left-right political ideology.

The Optimates like Pomey favored the dominant oligarchy of Senators, aristocrats, and landowners (right), and the Populares sought popular support against the dominant oligarchy favoring plebs and soldiers (left) or simply their personal ambitions (right).

This is analogous to the Tories and Whigs of Britain, the Reds and Whites of Russia, the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, or another political dichotomy in history. This is because what happened in the Roman Republic was not unique. Instead, it was a naturally occurring system on which all basic political parties are based.

Plebs and Patricians were not a Roman invention. They were a manifestation of our inherent human tendency to form groups. This is especially evident in a Democratically minded Republic where the freedom of speech leads to the ability of people to declare themselves, as Thomas Jefferson points out more than once.

“Men by their constitutions are naturally divided into two parties: 1. Those who fear and distrust the people, and wish to draw all powers from them into the hands of the higher classes. 2. Those who identify themselves with the people, have confidence in them, cherish and consider them as the most honest and safe, although not the most wise depositary of the public interests.

In every country these two parties exist, and in every one where they are free to think, speak, and write, they will declare themselves. Call them, therefore, Liberals and Serviles, Jacobins and Ultras, Whigs and Tories, Republicans and Federalists, Aristocrats and Democrats, or by whatever name you please, they are the same parties still and pursue the same object.

The last one of Aristocrats [federalists] and Democrats [anti-federalists] is the true one expressing the essence of all.” —Thomas Jefferson to Henry Lee, 1824. ME 16:73

The Take Away

Neither the Optimates, the Senators, or the Patricians were inherently wrong in their acquisition of wealth or power, or their preference of government. They were the ones fighting for the Republic after all. Neither the Populares or Plebs were entirely right in their support of the liberal General Caesar, although they did usher in the age of the Roman Empire and despots with their populism.

Their history does not give us a lesson in right and wrong, but more a lesson on the nature of dualities, how people divide into factions, how inequality corrupts governments, and how things can have paradoxical effects. The Republicans fought for the Republic, but they did so by being oligarchical. This oppressed the Plebs who looked to a despot to lead them.

When Caesar was killed, after declaring himself King for life and God (an early version of the divine right of kings), the Senate was executed, and the age of Benevolent Monarchs like Augustus and flat out Despotic Tyrants like Nero began. One might think, like America’s founders, that the Tyrant would have been overthrown, but when the aristocrats are too oligarchical or the people too oppressed, they look to people like Caesars, Lenin, Solon, Mussolini, and Napoleon as liberators.

Italy wouldn’t see another Republic until the time of Fibonacci and Machiavelli.

TIP: Both extreme inequality and equality corrupt governments. Rome offers us historical accounts of both happening.

FACT: These groups weren’t Rome’s first left-right groups, but they stand out as they tell the story of the Fall of the Great Republic, the populism of Caesar, and the corruption of the oligarchical Senate.

Fall of The Roman Empire…in the 15th Century: Crash Course World History #12.