People don’t seem to understand Machiavelli, but a close reading of the book proves that Rousseau is right, unsurprisingly, like every other Republican in history, Machiavelli was one of the good guys and didn’t have overly simple ideas like “the ends always justify the means”. He is the father of political science, not a brain dead power hungry Tyrant. “For the love of liberty”, let us stop smearing the man’s name with our oversimplifications.

Machiavelli Said, “the Ends Justify the Means” myth

Did Machiavelli Actually Say, “the Ends Justify the Means?”

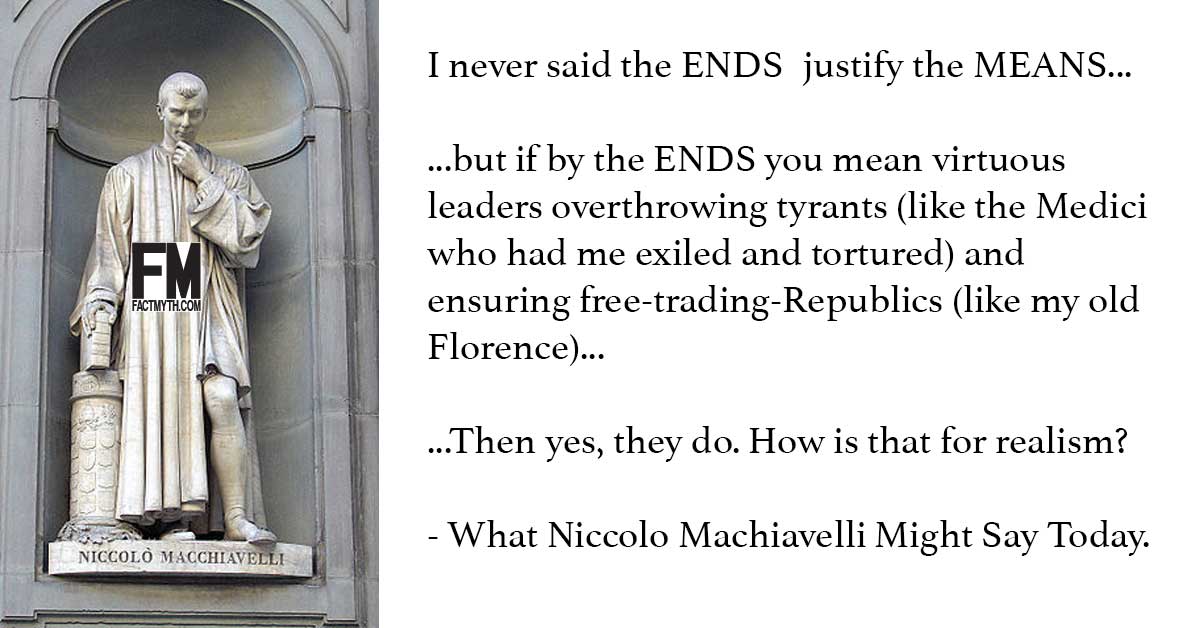

Niccolò Machiavelli never said, “the ends justify the means,” although he did allude to a complex version of the concept in his Prince and other works. [1][2][3]

Machivelli said things like:

“For although the act condemns the doer, the end may justify him…”

Discourses: I, 9

See more related quotes.

In all these quotes, some faithful translations, some liberally rephrased over the years, some offered on this page, some not, the meaning is the same:

Machiavelli in all cases is implying that “the means” matter, and “the ends” don’t magically justify them, yet sometimes it is worth accepting all the ramifications of “unjustifiable means,” and the damage they do to one’s reputation, for the end goal.

In other words the ends don’t cancel out the means in every respect, but they may none-the-less justify to some extent the original less-than-virtuous actions needed to secure the ends (it is a warning not to be too pious when dealing with politics, not a suggestion that putting aside virtue has no consequence).

Furthermore, Machivelli points out, that as far as the opinion of others is concerned, appearances matter more than action. “Men judge generally more by the eye than by the hand… one judges by the result.”

Both of the above concepts are notably different than the idea that “any means are magically justified by ends.”

The above can be gleaned from the Prince chapters 6 – 9, especially Chapter 8 where he describes “criminal virtue,” and chapter 18. Furthermore, the concept can be found throughout Discourses on Livy.

With that in mind, although it isn’t fully misguided to attribute an ultra-realist grey area line of political thinking to the Father of Modern Political Science Niccolò Machiavelli, this consequentialist misquote is an over simplification of Machiavelli’s realist Republican philosophy and the phrase itself never appears in his work in the way in which it is often passed around in modern times (all an isolated and specific sentence “the ends justify the means – Period”).

Below we further explain this stance.

The Difference Between Consequentialism and the idea that “the Ends Justify the Means.”

Before we dig into what Machiavelli did or didn’t say, we should quickly explain consequentialism.

Consequentialism or Utilitarianism, the Greatest Happiness theory, justice, fairness, the core theory of moral philosophy is often mistaken as the philosophical idea that “the ends justify the means – Period.”

That snappy justification for everything “sinful and wicked” sounds good on paper at first to some realists, but in practice, it is a slippery slope to despotism and immoral horrors. See Hitler, eugenics, and other horrors like that.

A simple maxim like this is needs revision, and the actual utilitarian theories of everyone from Plato to Bentham, to Mill, to Rawls essentially refute the simplistic take on the concept. These are all good theories from the original utilitarian theory of Morals and Ethics.

So it is no surprise Machiavelli, the Father of Modern Political Science, presents a more complex argument than the famous, but simplistic, pseudo-consequentialist quote alludes out of context. Machivelli was not the odd philosopher out, he was the father of the modern line of thinking that led to the other later philosophers.

Proving Machiavelli Never Said, “the Ends Justify the Means.”

Although we can point to different parts of the book, including most of chapters 6 – 9 to make the points on this page, some of which I leave out, the best evidence has already been pointed out correctly by CSMonitor.

The closest Machiavelli comes to actually saying “the ends justify the means” quote is from Chapter XVIII of “The Prince.”

Men judge generally more by the eye than by the hand, because it belongs to everybody to see you, to few to come in touch with you. Everyone sees what you appear to be, few really know what you are, and those few dare not oppose themselves to the opinion of the many, who have the majesty of the state to defend them; and in the actions of all men, and especially of princes, which it is not prudent to challenge, one judges by the result.

For that reason, let a prince have the credit of conquering and holding his state, the means will always be considered honest, and he will be praised by everybody because the vulgar are always taken by what a thing seems to be and by what comes of it; and in the world there are only the vulgar, for the few find a place there only when the many have no ground to rest on.

In this passage (which is subject to different translations), Machiavelli is saying “one judges by the results,” not “do anything necessary to get your desired ends with no regard for virtue.”

He is poking fun at Princes, which fits with the idea that the Prince is essentially written as satire and is trying to teach virtuous leaders how to overthrow tyrants and people how to form Republics.

The Prince is written to look like a realist guidebook for hereditary princes. In reality, it is a mix of underhanded insults and of underhanded tactics for virtuous leaders who lacked the criminal virtue needed to ensure power in a world full of con men and tyrants.

As Rousseau says, “his is the book of Republicans.” If you agree with Rousseau, as I the author clearly do, then like me you might think: “ah, how appropriately Machiavellian!”

Machiavelli hinted, both in his stated words and on the sly, that “if a virtuous leader came along to overthrow a tyrant by force, that the ends would justify the means, that they would be judged by the results, not the action of overthrowing.” He used backhanded language to lambast the Medici family who had him arrested, tortured, and exiled from the government when they took over his Republican Florence and turned it into a hereditary principality.

Beyond this, Machiavelli used a realist tone and explored the idea that Princes who come to power through might tend to have an easier time retaining power, in chapters 6-9. He alluded to his thought that “criminal virtue” is helpful for ensuring a show of strength when rising to rule. He noted that criminal acts are not those of great leaders, but also noted that it is perhaps better for a good leader to use a few calculated wicked tactics than for that leader to lose to an even more evil leader who employees criminality as a matter of course.

Thus, the point is nuanced, but Machiavelli is hardly just saying “the ends justify the means, morality doesn’t matter, feel free to use this as a justification for any questionable policy.” Not at all.

Machiavelli’s core point then is no different than those made by other philosophers. The point is that one should seek “the greatest happiness,” and in doing so, one must be willing to embrace some vice and sacrifice some virtue. That point is also summed up in the first line of Mill’s utilitarianism. In the rest of the book, he describes secondary principles that temper this first principle. The same is true for Machiavelli. We can read a section as a call for shady tactics, but his work in total is a realist account of political tactics, history, and a general call for Republicanism.

Our political ancestors and great philosophical moralists did not condone all means to the desired ends; their theories are much more enlightened, even an uber-realist like Kissinger knows this.

PHILOSOPHY – Ethics: Consequentialism [HD].DO THE ENDS JUSTIFY THE MEANS? The ends can sometimes justify the means, and the ends are often more important than the means. Sometimes, one must muster up criminal virtue to ensure an end which brings the “greatest happiness,” but one must understand that we are talking about the “greatest happiness” theory here. Thus, people should consider the philosophy of consequentialism and consider the morality of the means as well as the result of the ends, and not just seek their ends by any means without consideration. Machiavelli as a political thinking, virtuous master, and republican would no doubt apply the same sort of reason to the seeking of a perfect happiness theory. Truly, one could argue, that only a tyrant would consider ends to justify means – period…

An Introduction to Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince- A Macat Politics Analysis.ALL STATES, all powers, that have held and hold rule over men have been and are either republics or principalities. – The first line of the Prince

“… the governments of the people are better than those of princes.” Book I, Chapter LVIII of Livy

- The Prince by Nicolo Machiavelli Written c. 1505, published 1515 Translated by W. K. Marriott

- Political misquotes: The 10 most famous things never actually said

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau (The Social Contract page 37).

K.Smith Did not vote.

The Prince, XVIII

“….nelle azioni di tutti li uomini, e massime de’ principi, dove non è iudizio da reclamare, si guarda al fine. Facci dunque uno principe di vincere e mantenere lo stato: e mezzi saranno sempre iudicati onorevoli e da ciascuno lodati”.

“…in the actions of all men, and most of all of Princes, where there is no tribunal to which we can appeal, we look to results. Wherefore if a Prince succeeds in establishing and maintaining his authority, the means will always be judged honorable and and praised by each one.

So sure, he didn’t specifically say “the Ends Justify the Means,” but….

Lorna Supports this as a Fact.

Real truth and fact.

Thank you

andre Did not vote.

Very long article. Unfortunately, your poor research renders all the information you listed in vain, because nobody has ever claimed that the specific passage you used to justify that Macchiavelli did NOT say, ‘the ends justify the means’ is the the passage in which he said, ‘the ends justify the means’.

In other words, your article is a straw-man fallacy, from start to finish.

The action is excused, and the outcome excuses it.

Niccolò Machiavelli

That is what you were looking for.

Thomas DeMicheleThe Author Did not vote.

So first off, I can’t find your translation in any translation I’ve read. This makes me question if it is you and not I who have perhaps not done the research.

That said, I don’t want to focus on that, we are both grappling with English translations of a book from the early 1500s written in foreign language.

So let’s say, if you have a translation that actually uses the quote you say (which I’ve ONLY seen on the internet and never in his actual works) then please share it and I’ll cite it clearly on the page.

That aside, my rebuttal:

So there are some places in discourses and the prince where machivelli eludes to this concept. In all cases he says things like:

“For although the act condemns the doer, the end may justify him…”

The Discourses: I, 9

That should be translated to “although the act has weight and may condemn the doer, in the end the end result may justify them.”

This is the point the article is making.

Reading this as, “the original criminal action is magically excused by results” (which I would argue is exactly how many modern readers know the quote) is a shallow reading of the virtuous machivelli (and I am trying to use that misunderstanding to introduce people to the real Machiavelli).

He is teaching criminal virtues of wicked men, and showing how they wiggle out of past sins, but he doesn’t suggest the original sin has no ramifications.

With that said, I’ll take greater care to cite more passages and make my point more clear.

This dawned on me after reading his works, reading “ends justify the means” memes online, and then realizing people’s perceptions of machivelli were very different than what he himself presents in his work. Clearly machivelli was a liberal republican who studied the art of war with a heavy heart and taught tactics with the hopes they would be used to secure liberal republics and thwart tyrants.

Thus, it isn’t surprising that he taught one how to use criminal virtues, but warned that doing so would detract from greatness (even in cases where… doing so was worth the costs.)

All that said, thank you for pointing out that the accuser quote (from the same chapter I am citing, chapter 8) should also be citied.

One last thing to keep in mind is that there are many translations of machivelli’s works, and not every translation to English offers us the same exact phrasing. I personally have had to thumb through different translations to fully understand just what people are quoting here, so the critical insight you offer is appreciated despite my rebuttal.

Also, ultimately this is my impression, plenty of room for me to be wrong and others to be right. Just with machivelli’s back story and own words it’s hard to see him as a cut throat errand boy of tyrants and not as the father of modern republican realist philosophy.