Plato’s Five Regimes

Plato’s Five Regimes: Understanding The Classical Forms of Government as Presented By Plato

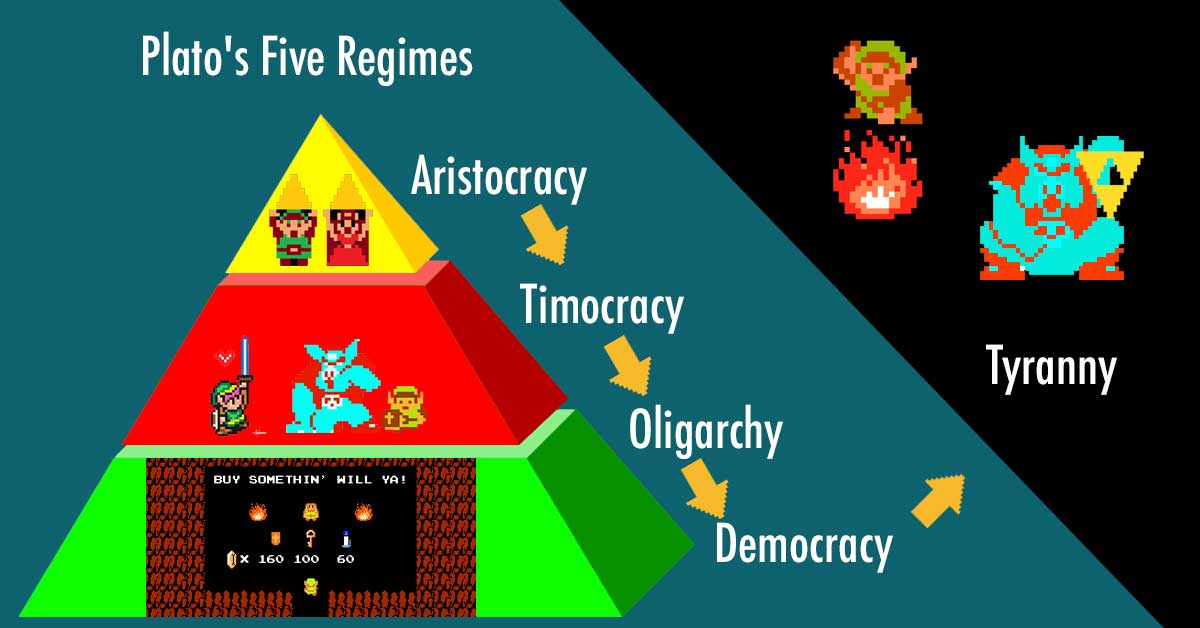

Plato discusses five regimes (five forms of government) in his Republic, Book VIII. They are Aristocracy, Timocracy, Oligarchy, Democracy, and Tyranny. He then goes on to describe a mixed-form which we can call a Kallipolis (beautiful city) or “ideal Polity,” his “ideal mixed-Republic”.[1][2]

An Introduction to Plato’s Five Forms of Government and General Theory From his Republic

Plato’s five forms of government can be understood, in order of the most desirable to least desirable (with each form descending into the next), as:

- Monarchy and Aristocracy (rule by law, order, and wisdom; or, as Plato puts it, rule by the wise; like ideal traditional “benevolent” kingdoms that aren’t tyrannical),

- Timocracy (rule by honor and duty; or, as Plato puts it, rule by honor; like a “benevolent” military, Sparta as an example),

- Oligarchy (rule by wealth and market-based-ethics; or as Plato puts it, rule by wealth and land ownership; like a free-trading capitalist state),

- Democracy and Anarchy (rule by pure liberty and equality, where the people vote on and make laws; or, in Aristotle’s terms, “rule by the many;” like a free citizen), and

- Tyranny (rule by fear, without just laws; like a despot).

Then, a [ideal] Polity, the most desirable form, is a “balanced” mixed-government (an “ideal” mixed “Republic“) that draws from all the forms except tyranny (as its purpose is to avoid tyranny).

The idea here is that each higher form restrains the lower forms in an effort to maximize the virtues of all forms (like liberty and equality) and to minimize their vices (like illiberty and inequality). A separation of powers and checks and balances in a Republic, so to speak (a concept well understood via Plato’s chariot metaphor).[3]

On a table, the forms look like this (with the note that all lawful forms are mixed to create an ideal mixed-Polity/Republic):

| Plato’s Five Regimes | Correct (Lawful) | Deviant (Not Lawful) |

| One Ruler or Very Few Rulers | Monarchy /Aristocracy (intellect and wisdom based) | Tyranny |

| Few Rulers; a Military State | Timocracy (honor based) | |

| Few Rulers; a Capitalist State | Oligarchy (greed based) | |

| Many Rulers | Democracy/Anarchy (pure liberty and equality based) |

This is then not only meant as a governmental theory, but an overarching theory for every aspect of life. It is a theory of the soul, of the classes, and of all things in general really.

For my money, this is a great starting point for understanding both the real government types and the human condition, which is probably why we still read a book from 380 BC.

Below we explain how Plato’s five forms should be understood classically and in the modern-day, both in a realist sense, and as a general metaphor. First, some notes on understanding this in the context of Plato’s works and in terms of real governments.

The four governments of which I spoke, so far as they have distinct names, are, first, those of Crete [monarchy] and Sparta [timocracy], which are generally applauded; what is termed oligarchy comes next; this is not equally approved, and is a form of government which teems with evils: thirdly, democracy, which naturally follows oligarchy, although very different: and lastly comes tyranny, great and famous, which differs from them all, and is the fourth and worst disorder of a State. – Book VIII

Notes On Understanding Plato’s Government Types

Before we jump right into explaining each government type, it’ll help to understand the following points.

The Greek States as Archetypes

Plato uses three Greek states to illustrate his government types.

He describes Crete as a Monarchy, Sparta as a Timocracy, and Athens as a Democracy to illustrate the difference between the three states, their cultures, their laws, and their government types. He then also discusses these three governments in detail in his Laws.

Knowing this we can look to Laws to better understand the spirit of Monarchy/Aristocracy, Timocracy, and Democracy.

When we consider that Athens was a free-trading Republic with a history of Oligarchy, that Sparta became Oligarchical, and that Laws also discusses tyranny, we can see how Plato’s original “Spirit of the Laws” contained in his Laws has a lot to teach us about the types of governments found in his Republic.

The Republic only touches on Athens, Sparta, and Crete, Laws is a tome that examines each in detail. In this respect, when exploring Plato’s forms, it helps to draw from at least these two texts if not his whole library to grasp his full meaning.

Details aside, the simple idea is Athens, Sparta, and Crete represent Democracy, Timocracy, and Aristocracy. The complex idea is that Plato uses each to describe different mixes of the forms, so the full point is not so simply summed up (if you do a “command find” on Laws and the Republic, especially an annotated Laws, you’ll see what I mean; that is, these states are vehicles for conveying an idea about the forms of government in both pure and mixed form.)

Each Higher Form Knows the Lower Forms

Each form, tyranny aside, becomes less “conservative” and more “democratic” (or “liberal”) as each form dissolves into the next. If we considered only two forms, we would say it moves from Monarchy/Aristocracy to Democracy/Anarchy (from the conservative one to the liberal many)…. where it becomes anarchy and then tyranny, thus going from the tyrannical many to the one again.

Monarchy/Aristocracy is all about law, order, and restraints, Democracy/Anarchy is all about total liberty and equality.

Meanwhile, Oligarchy is more liberal than Timocracy, but it has less orderly restraints. It is always a trade-off, a balance (AKA Justice). That is why Plato suggests a “mixed” form (like the one we have).

TIP: For Plato, “wealth” is the root of most corruption, as excessive wealth breeds corruption and results in social, political, and economic inequality.

The Ideal Aristocracy

The ideal Aristocracy has the virtues of all the lower forms to some degree. It is rule by the wise; sagely aristocrats who know all the forms. It is not the rule of posh monied oligarchs who fancy themselves aristocracy (that is oligarchy).

This concept of knowing the lower forms is then true for each other form on down, they all have attributes of the lower form to some degree.

We can say, extrapolating from Plato’s theory, that Aristocracy and Timocracy both know duty and honor, but where this is the highest good of a timocrat, the aristocrat also knows the vices and virtues of the other forms too (and is thus “wise”).

That said, we could consider Aristocracy to know a higher form of duty, a moral duty, while timocracy knows a slightly lower form of duty that is more ethics-based. This goes beyond the scope of Plato, but consider De Officiis (On Duties) by Cicero where he explains the different Higher and Lower order forms of duty.

Monarchy and Aristocracy Treated as the Same by Plato; as are Democracy and Anarchy

Here Monarchy is considered the same as aristocracy (even though one is ruled by “one” and the other “the few) and Democracy is considered the same as Anarchy (because they are both “ruled by the many” and Plato is trying to make a point about how Democracy leads to Anarchy and then to Tyranny).

The Republic’s Government Types are also a Metaphor for the Human Condition

Plato’s Republic equates each form with a man, with a class structure, and with an aspect of the soul. This should be understood metaphorically first and foremost, allowing one insight into difficult ideas, and not literally. It is a philosophical theory of everything, here we are focusing on the more realist aspect of governments.

I won’t be suggesting that we teach people Plato’s noble lie (the strange tangent about the metal-colored souls) for instance. I personally find some of the specifics Plato puts down as distracting from his underlying theory. There will be idealism injected here (as this is Plato), but the foundation is about as real as it gets and is directly applicable to modern political life. See an overview of Plato’s Republic and its themes.

The ideal state from Plato’s Republic using 8-bit. For educational purposes only.

Aristotle’s Slightly Different “Realist” Theory

Aristotle describes a very similar theory in his Politics, so keep that in mind. Even though we are discussing Plato’s forms, understanding this will give you the basics of Aristotle and the basics of the modern actual forms of governments as well (so it isn’t just a neat theory from 380 BC, it is actually pretty darn useful as a realist guide to modern governments-in-action and as an idealist guide to the philosophy behind ideal utopian governments).

Extrapolating Plato’s Theory: Tyranny Beyond Plato

Extrapolating Plato’s theory, one can think of things this way:

Each type that isn’t “tyranny” can become tyrannical (can become unlawful, or corrupted). It can happen in order, where Democracy collapses into Anarchy (the first tyrannical form; a corrupt Democracy) when [in Plato’s terms] the people reject the corrupt Senate.

Then Anarchy descends into tyrannical oligarchy (a corrupt Oligarchy) when Plato’s tyrant Oligarch takes power. Then that becomes a tyrannical police or military state (a corrupt Timocracy) as the Oligarch begins to become a true despot (purging his opposition). Then that becomes a tyrannical despotic totalitarian government (a corrupt Monarchy / Aristocracy) when the despot takes full control.

Here I would also note, there is no good reason that steps can’t be skipped. For example, if a hereditary Monarchy goes from a good King to a very bad King, they could go straight to tyrannical despotic totalitarianism without ever becoming Democratic.

Plato’s Republic is a metaphor in this sense, meant to be extrapolated and thought on I think, not an exact science.

Other Philosophers on Tyranny: Thinking on the above, Hobbes’ words come to mind. Hobbes eludes [paraphrasing] “Monarchy and Tyranny are the same form, their difference is only our opinion of them.” That is one realist way to look at things. With that said, Montesquieu would argues the difference is not opinion, but instead their adherence to just law, and Rousseau would add that it is the adherence to the General Will inherent in a just Social Contract that separates the tyrannical forms from the non-tyrannical ones.

Illustrating Plato’s Forms With Other Tables

Above we offered one table, the one that aligned fully with Plato’s book.

Since there is no right way to do this we have opted for two different models to illustrate other aspects of the theory.

NOTE: The table below is using Aristotle’s table to place Plato’s theory on a table. Aristotle puts Oligarchy on the “deviant” side, Plato really only places tyranny on his version of a “deviant” side. So this table shows an Aristotelian version of Plato’s theory.

| Correct (lawful) | Deviant (corrupt) | |

| One Ruler or Very Few Rulers | Monarchy /Aristocracy (intellect and wisdom based) | Tyranny (fear based) |

| Few Rulers | Timocracy (honor based) | Oligarchy (greed based) |

| Many Rulers | Democracy (pure liberty and equality based) | Anarchy (pure liberty and equality based) |

Or on a table that shows all the forms aside tyranny as “lawful” and includes his Polity (sometimes I say this word to imply an ideal polity or ideal republic, as has been done often in philosophy):

NOTE: Both tables on the page were created from our studying of Plato’s work (this chart treats Oligarchy as a lawful system; this is probably closer to the intent of Plato’s theory, and certainly lines up better with reality, especially when you consider a free-trading Republic or Capitalist State like Athens or America). This table below is my own theory extracted from Plato’s work.

| Plato’s Five Regimes Expanded | Correct (lawful; Ruled in Line With the General Will) | Deviant (Special Interest Before the General Will) |

| One Ruler or Very Few Rulers | Monarchy /Aristocracy (intellect and wisdom based) | Despotic Tyranny (fear based) |

| Few Rulers; the Ideal Polity | The Polity (a Mixed Republic the draws from the above forms to protect against tyranny). | A Despotic Republic (a Mixed Republic that is not balanced enough to protect against tyranny). |

| Few Rulers; a Military State | Timocracy (honor and merit based) | Tyrannical Timocracy (military state gangsterism; like a despotic Junta) |

| Few Rulers; a Capitalist State | Oligarchy (wealth based) | Tyrannical Oligarchy (greed based; a Plutocracy) |

| Many Rulers | Democracy (pure liberty and equality based) | Anarchy (pure liberty and equality based) |

NOTE: In his theory Plato says each form degrades into the next, but I’m fairly certain that each form can itself become tyrannical (i.e. in the chart below, a form can degrade “sideways” and become its deviant equivalent)

The Five Regimes Explained

With the above notes covered, let’s explore the Five Regimes in detail.

These five regimes (five forms of government) can be understood as being presented in order of desirability with each form collapsing into the one below. The excerpt is the Ideal-Republic-Polity which we will describe last.

NOTE: A figure like Marx will place emphasis on economy when discussing the forms, Aristotle will emphasize how many rule (what a realist), and Plato discusses the forms based on virtue. In practice, we consider all these “attributes of government“.

TIP: To reaffirm the above, and to spoil the ending, pure governments aren’t very useful. The idea is to understand all these types as aspects of government and then to mix them in the right way to form an ideal Republic.

The above forms can be understood in more detail as:

Aristocracy (and Monarchy)

Aristocracy generally speaking just means a state run by the best and brightest. The problem is this typically gets translated into “a state-run by those with the richest and most prestigious parents or most money” (a hereditary or oligarchical aristocracy).

That viewpoint of aristocrats as snooty upper-class oligarchs isn’t right when discussing classical forms of government. An ideal aristocrat knows all the other forms, has mastered them, and thus has the wisdom and experience to help guide all of them away from their vices while respecting their virtues (they are elite in their mastery, not in their bloodline or pocketbook size).

The idea isn’t to inhibit the other “forms,” it is to wisely provide necessary restraints to ensure the other forms can function in perfect order.

If we imagine a chariot, the driver is an aristocrat and horses are the other forms. The charioteer guides the horses, he does not destroy them or look down on them or directly control them. Just as a wise sage might have the experience and wisdom to reign in the pleasure-seeking they enjoyed in their youth, the aristocrat reigns in the vices of the state and guides its virtues.

Simply, and to Plato’s point, if we think of each form as an aspect of the human condition, we can say that aristocracy is that which is wise enough to pull from all the forms of government.

As said above, today we may think of an aristocracy of being somewhat oligarchical or hereditary, where an aristocrat is posh, has a rich dad, got a small loan, has a really well-managed portfolio, and even got a job on special orders from the King… but that style of hereditary wealth-based aristocracy is all more like Oligarchy (a lower-form).

Aristocracy more describes rule by the impossibly wise, what Plato called a philosopher king(s). Aristocracy, roughly speaking, means “highest”. The highest of classes upholds the highest of ideals like justice, wisdom, moderation, and temperance. It is like a technocracy (fact and intelligence-based) mixed with a kritarchy (moral and wisdom based), it knows animal lower-order pleasure-seeking virtues, but it is not guided by them.

Plato considers Monarchy and Aristocracy “essentially the same,” Aristotle being more realist separates these types by the very empirical question “how many people rule”.

Here we focus on building the ideal state as a metaphor, so there is not much difference in quality between how a philosopher king or philosopher kings would rule. The highest forms are absolute, so anyone tuned in enough will hear the same message, and anyone wise enough will make the right judgments.

The general idea here is that those who best know the higher and lower forms (speaking here broadly in terms of virtues, aspects of the human condition, and forms of government; see Plato’s Theory of Forms), and that those who are generally the wisest, should guide the state.

The perfect aristocrat has all the virtues of the timocrat, the oligarch, and the democrat, and they know the tyranny and anarchy in their own self and know how to control it. Thus, this isn’t a statement on the other forms being less-than in general, they are full of desirable traits actually, it is a statement on the idea that the one who knows all the forms and who desires balance more than just honor, money, liberty, or equality is best suited to guide the state toward maximizing honor, wealth, liberty, and equality (where an oligarch might see money as “the greatest good,” the aristocrat knows how to maximize by tempering it with other forces to create “the greatest happiness for all“).

This is to say, generally, classically speaking, saying an ideal state is rooted in an aristocracy is not a judgment of wealth, social status, or bloodline. It is a judgment on wisdom (which is gained through experience, which in practice just happens to be easier to obtain by the higher classes in our modern society, as they, in our current oligarchical system, have better access to higher education and other such perks).

One can see how this being the highest form would be misunderstood, but remember, we are saying “a government of virtuous philosopher kings” not “a government of hereditary oligarchs”. Sometimes the King-in-practice has been raised to be a philosopher king, in a case like this, the two theories simply collide (James VI comes to mind as a close-as-we-get example).

In America, the Supreme Court is the closest we get to this. I’d like to put other positions here (like Congress, the President, deep state intellectuals, etc), but there is too much room for misunderstanding. Plato said that no philosopher king actually existed in his time, it would be a little silly to place anyone in the top tier without much debate as it leaves too much room to place despots here (tyrants love to imagine they are philosopher kings; so let us clearly state, none have ever been such a thing).

Loosely speaking, when we say aristocracy, we mean the best for the job. When we say philosopher king, we mean the ideally best for the job of leading the state, soul, etc. That is a tall order.

Roughly speaking, taking Plato’s whole theory into account, we can say: The aristocratic state descends into timocracy when a love of honor becomes more important than balance, likewise, it descends into oligarchy when a love of money is more important, likewise into Democracy when liberty and equality are favored.

Or, more in Plato’s terms, this time speaking just of the descent into timocracy, aristocracy becomes timocracy when (using a father and son metaphor): The aristocratic father encourages the rational part of his son’s soul. But the son is influenced by a bad mother and servants, who pull him toward the love of money (oligarchy). He ends up in the middle, becoming a proud and honor-loving man, a timocratic man. In words, when the aristocrat allows the state to become unbalanced by a love of honor, wealth, liberty, or equality, the aristocratic state descends to a lower level.

TIP: Classically the male and female are used metaphorically, so it is with Plato. Fathers represent reason and aggression (aristocracy, timocracy, and tyranny) and mothers represent pleasure-seeking and empathy (oligarchy and democracy). If that seems sexist against women, consider the tyrannical man (the worst) is a male figure. Also note, this is metaphor. Learn more about male and female symbolism.

Timocracy

Generally speaking, Timocracy is a state-run like a honorable military. It is a state based on honor, duty, hierarchy, and order.

This is more what we think when we think of Britain in the best of times with its House of Lords and wise Kings and Queens, or what we think of when we think of Sparta, or even King Arthur and his round table Knights. It is not an imperial military seeking fear, wealth, or other lower-order things, it is rather speaking to the structure within a military where order, honor, and duty drive a chain of command toward a common goal.

Like with a military, in a Timocracy you would find some form of merit-based ranking system (at least for some positions) to determine social hierarchy.

Money, liberty, and equality are not the virtues of timocracy (to the extent that Plato’s timocratic class doesn’t use money, like the Spartans), and fear and disorder are in many ways its opposites. It is the highest form of government that isn’t aristocracy.

Keeping in the spirit of timocracy, any master/sage with humility would see themselves as a mix of timocracy-aristocracy. That really more-so describes a James VI, Alexander the Great, or George Washington, one who is more Commander-in-Chief or General than philosopher King.

In America our military, President, and deep state is this, and so is a rank-and-file soldier. Obviously some positions are at the top of this pyramid. And here I’ll note vitally, each sphere is its own pyramid, aristocracy only peaks out of the top, it isn’t like any class (any aspect of the soul, any form) is fully below the others. It is just again, like the charioteer, being reigned in and directed by the higher forms.

On Sparta, Timocracy, Landownership, and Honor and Duty

Timocracy is easy to confuse with oligarchy because Sparta is used as an example by Plato.[4]

In Sparta the landowning Spartans were the upper-class timocrats, and they would have all owned land.

The thing is, I really think what Plato was getting at is the concept of honor and duty (not the trivial act of land ownership; yes the upper-class Athenians owned land too, maybe that is what Aristotle was referring to in Nicomachean Ethics (Book 8, Chapter 10).

The idea is less about land and more about the fact that the Spartans ran their country like a virtuous military.

This makes more sense if we consider the Republic as a metaphor for the soul and classes.

Clearly the Timocratic man is to be compared to the auxiliary class, thus his virtues are honor and duty, like the Spartan.

Meanwhile, the landowner Oligarchs of Solon’s time who enslaved the lower classes were, as it says in the Athenian Constitution, Oligarchs.

To rephrase the above, to Plato, a Timocracy is like Sparta. Their currency isn’t money, it is honor and duty. They defend liberty and equality, and they defend their producer class oligarchs, but they themselves are like the Chivalrous Knights of the middle-ages.

The Descent of Timocracy to Oligarchy

Timocracy descends into oligarchy as the love of money grows and those who have more wealth and property begin to write the laws. This by the way is literally what happened in Sparta. How prophetic, or probably for the time, observant (Sparta hadn’t made its descent into oligarchy and then defeat at the hands of Rome yet, but happens not too long after Plato’s time). Learn more about Sparta, its government, and its fall to Oligarchy.

“After this event there was contention for a long time between the upper classes and the populace. Not only was the constitution at this time oligarchical in every respect, but the poorer classes, men, women, and children, were the serfs of the rich. They were known as Pelatae and also as Hectemori, because they cultivated the lands of the rich at the rent thus indicated. The whole country was in the hands of a few persons, and if the tenants failed to pay their rent they were liable to be haled into slavery, and their children with them. All loans secured upon the debtor’s person, a custom which prevailed until the time of Solon, who was the first to appear as the champion of the people. But the hardest and bitterest part of the constitution in the eyes of the masses was their state of serfdom. Not but what they were also discontented with every other feature of their lot; for, to speak generally, they had no part nor share in anything.” – The Athenian Constitution By Aristotle

Oligarchy

To Plato, an Oligarchy is system of government that distinguishes between the rich and the poor, where the rich rule the poor. Sometimes people say “a timocracy is where landowners rule,” but this is just as wrong as saying aristocracy is where the wealthy rule, no, both of these are oligarchy!

This form of government is what most types of economic systems create.

Where aristocracy is based on intellect and wisdom, and timocracy based on honor, duty, and order, oligarchy is based on wealth.

This form of government doesn’t take much imagination to understand (see an example of oligarchy here), but I’d caution people to remember that it is only the third of five regimes.

Oligarchy may not have the virtue of an aristocracy or timocracy, but it has a degree of order and virtue within its own sphere of production and luxury. As if by an invisible hand, it isn’t actually as bad as it gets by any degree.

Sure, inequality isn’t much of a virtue, but oligarchical sub-systems work well, and certainly, oligarchy trumps pure tyranny or anarchy (generally speaking).

The problem is oligarchy descends into democracy via a populist revolution when inequality gets too great. AKA what everyone should be concerned about right here, right now, 2017 modern western times (although I’ll note again, this is part metaphor, so we need to be concerned about all the forms and their descent in our current purposefully mixed government; one could easily make a case for democracy becoming tyranny as well and Plato does of course; or for aristocracy becoming timocracy and oligarchy. Don’t try to think too specific, but do generally consider each story of each form as a metaphor as it applies to each form of government, as that applies to mixed governments, and as that applies to the general human condition. After all, that is literally the point of Plato’s book).

TIP: When Solon created the first western liberal democracy, the first modern democratic trading republic, of note (Athens) he did so by overthrowing the oligarchs peacefully. He removed all credits and debts. Plato probably didn’t see the Poet-King Solon through the best light, but here we should note that perhaps what Plato is really saying for his time is that he felt Athens had gone from pre-Solonic Oligarchy to his modern Athenian Democracy by lottery? Maybe he was predicting the rise of Alexander the Great and Fall of Athens to Rome? See the Athenian Constitution and the story of Athens.

Democracy (and Anarchy)

Democracy is form of government based on the virtues of equality and liberty. It is a purely popular government-run by popular sentiment. What do all citizens want? They want what a child wants, they want total liberty and total equality (they want the extremes of classical liberalism).

The problem is, when everyone has total liberty and equality, the state is destined to descend into anarchy and then tyranny.

What is that you say? Why is our beloved democracy so low on the list?…

… because the three above forms had a sense of order and a tolerance for inequality, but democracy will lift up an oligarch as a philosopher king and will see themselves the equal of James VI or Plato.

Without a respect for the natural hierarchies, anarchy descends from democracy, and from the temporary anarchy the tyrant arises.

The tyrant is going to be a timocrat or oligarch, because those are the only two types who know how to get and hold power. See: How Democracy Leads to Tyranny From Plato’s Republic.

TIP: One of Plato’s main points here is to illustrate the descent from democracy to anarchy, to do this he doesn’t consider democracy and anarchy separately (but like with monarchy and aristocracy, he does denote that these things aren’t “exactly the same”).

TIP: In the French Revolution the populists overthrew the aristocrats (who were acting like timocrats and oligarchs). From this bloody battle, a messy form of anarchistic democracy arose for a short while, from the ashes of that the liberal tyrant Napoleon came to rule France. The problem here isn’t the Plato speaks in dialogue and metaphors, the problem isn’t his idealism, the problem is that he was right. Like Machiavelli’s Prince, if you try to read Plato to literally, then you might miss the message. Sometimes smart people bury points to avoid crucifixion, they crucified Plato’s Socrates after-all.

Tyranny

Democracy degenerates into tyranny where no one has discipline and society exists in chaos.

In this state the pendulum and scales demand balance. An extreme reaction meets an extreme reaction, and this is anarchy. Finally out of the dust arises a tyrant who [eventually] restores order through fear and might (either as an authoritarian military junta version of timocracy or as an authoritarian oligarch; Plato goes with the Oligarch version).

Democracy is taken over by the longing for freedom, then out of the state of anarchy, power must be seized to maintain order.

A champion will come along and experience power, which will cause him to become a tyrant. The people will start to hate him and eventually try to remove him but will realize they are not able.

It isn’t that the tyrant comes into power corrupt, no at first he appears a friend of the people (and he thinks himself such). However, once the shark has tasted blood, there is no stopping the feeding frenzy (exile doesn’t work, nothing works; feel free to ready Plato’s Chapter IX).

Tyranny then, after you the tens of millions dead, gives way to a new Constitution (if and when it does give way; typically as the result of war).

Those forming a new Constitution would be wise to root it in an aristocracy and provide safeguards in the form of law, culture, and class structure.

TIP: The only thing worse than a tyrannical man? A tyrannical man who has tasted blood in charge of the state. A Hitler or Stalin, but you know this. This is what all the history classes were about, why we don’t want National Populist Fascism (sure, it can be tempting to undo the aristocrats when they become timocratic and oligarchical; but Plato cautions us against it, and here we are discussing Plato; I’ve read Marx and Hitler, my only thought is that they could have both stood to focus less on the Jacobin workers’ revolutions and more on Plato’s theory). It isn’t the ideals we should fear, it is the tyrannical man a lack of restraints creates.

TIP: The tyrant, who is also the most unjust man, is the least happy. The aristocrat, the most just man, is the most happy. From this concept we can great “the greatest happiness theory“.

Polity

So, the above starts out pretty hopeful, then descends into darkness. That doesn’t seem like a great theory. So what do we do about it?

The answer is “the Polity“.

A Polity is a general term that roughly means “ideal mixed-Republic” (AKA the point of Plato’s book is to describe a polity that ensures all else).

For Plato a Polity is a mix of the forms, rooted in aristocracy, then timocracy, then oligarchy and democracy. Plato, fearing the lower-orders, goes a little autocratic and tries to create a rather rigid class structure, creates a noble lie to be taught to all children, and gets rid of poets (because they corrupt the soul with all their idealizing lower-order pleasures).

With that in mind, where Plato is a master in giving us a theory of state and soul that still works today, when we try to take him too literally, and don’t read into the metaphor, we end up with some sort of awkwardly distracting takeaways.

Sure, one can limit the influence of their deep poetic self in their own soul and reign in their wants of liberty and equality, but in a free modern-day Republic, we want to eat our cake too.

Thus, a polity is indeed ideally rooted in an aristocracy (properly understood as more like the rule of philosopher kings than oligarchs), then timocracy, then oligarchy, and then democracy, with each higher-order sphere having dominion over the other. But that aside, great care should be given (in creating the laws) to let oligarchy and democracy flourish “within their own spheres“.

The U.S. Constitution as originally written was actually a bit aristocratic (here meaning ruled by the wise few, our senators and President; neither of whom was meant to be democratically elected).

The Democrats did not have a tolerance for this aspect of Federalism and have since changed the laws to create a winner-take-all system (States’ Rights) and to vote directly on Senators (Populist Reformists).

In words, those necessary safeguards wisely put in place by the founders have been undone (with good intention perhaps, but still).

So, could we today here in 2017 elect an oligarch? Yes, of course. Democracy will always elect an oligarch if given time, it was the point of Plato’s book.

Luckily though, the U.S. is most certainly an ideal mixed-Republic with built-in safeguards. We elected Presidents, not Kings. The letter and spirit of the law still safeguard the Republic, but we are wise to, metaphorically, adhere to the basic structure Plato offered. If we limit liberty too much, or strive too much toward equality, if we dip our toes into the extremes of democracy without keeping it reigned in like the wild horses driven by a charioteer, it is at that point that we might start to see tyranny in action. This is to say, any state is in danger of incorrectness if they don’t adhere to what is fundamentally agreed on to be correct.

TIP: All that in one infographic to describe the class system that would result from this might look like:

Visualizing an Idealized Version of the Modern Estates (Social Classes) and the related “Class Struggle” and “Class Mobility” in terms of Left-Right Politics. If the Oligarchy and Democracy are not “restrained” (if speaking of estates they are not restrained from having too much influence in the first and second estates), we risk bringing the wrong part of Plato’s Republic to life. We already brought the right part of Plato’s Republic to life, our duty, as noted by the founders, is to continually safeguard it from tyrants. This is done through just laws and separation of powers and checks and balances (i.e. by the ideas contained in documents like the Constitution and Bill of Rights).

- Plato’st five regimes

- SparkNotes – The Republic Plato (for a useful summary from a different perspective).

- Plato’s chariot metaphor

- Timocracy

Alexander

My dear team of website,

I think that the oligarchy is the few of rulers, the minority of rulers in the rich is as plutocracy.

But the evidence of its is the communism of China, it is the oligarchy, the oligarchy is few, it could be the bad despotism, and the bureaucracy is the oligarchy, or the few lead his state.

I only add the idea in my view.

Thank you.