Paradigms, Dialectics, Abstractions, the Golden Mean, and Dealing With Dualities

The Nature of Abstractions: Dealing With Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis, Dualisms, Contradictions, Opposition, and Golden Means

We discuss theories that deal with the nature of abstractions and contradictions including, Dialectics and the Golden Mean theory, and offer a “synthesis” of these theories.[1]

NOTE: See “conflict theory” for more examples of how contradictions play out in the physical realm, below we discuss the general concept from Plato and Aristotle to Hegel and Marx, in its physical and metaphysical forms.

The Art of Abstraction, Contradiction, and Synthesis in The Sense We Mean it Here

When we say “abstraction” here, we mean the art of contradiction as found in Plato’s dialectic(s) AKA the dialectic method.

We mean taking a concept or statement, and finding its contradiction. It is a form of skepticism and analysis.

You say “numbers,” I say “the absence of numbers.” From this we derive 1 and 0. From 1 and 0 comes -1 (another contradiction of 1). From there comes the infinite set of possible numbers including fractions (“the difference” or “changes”) between -1…o…1. With that (in fact much less than that) and a little engineering, we can create the modern computer.

I ask, “what is justice?” You say, “it is the will of the stronger.” I then ask, “could it be the will of the weaker in some cases?”

Through the art of skeptical questioning, analysis, and contradiction we find deeper understanding. We can call this science/art by names like the Dialectic method, Socratic Method, Analysis, Abstraction, and Contradiction.

The idea is that we conceptualize a property, concept, proposition, or complex system or argument… and then we find deeper meaning through synthesizing the concepts we have uncovered with their antithesis.

This idea of abstraction, contradiction, synthesis, etc is the underlying concept here, and it is nothing more than a play on Plato’s dialectic (which itself is essentially the foundation of reason and logic).

From here it is all about applying this method in a number of forms to a number of physical, rational, ethic, and metaphysical systems (everything from labor and capital, to left and right, to short and tall, to 1 and 0, to the concept of justice)… just like we can apply the Socratic method to most anything, the same is necessarily true for this take on it.

Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis

To help you understand the above idea (which is rather central to philosophy old and new), let me offer a few examples to illustrate this “method of abstraction” (that term is used in different ways in the english language, but I mean it specifically to elude to a sort of duality or dualism abstracted out of a single concept; a the division of something conceptually into two opposed or contrasted aspects with the “mean between” considered):

Ex 1. where we start with a very simple concept (a single attribute/property) and draw out a single antithesis.

- We start with a single property as a concept/term (like short). A thesis.

- We draw out its opposite (like tall). An antithesis.

- We define a middle or “golden mean” (like average height). A synthesis.

- We can then consider degrees (like very short, short, average, tall, very tall). A range of degrees (with the mean being “the golden mean”).

Here if we have seen things short and tall, but we don’t have words for them, we can coin them. If we have only seen short and tall, from this we can posit average height. Or, from the conflict between the concepts of short and tall comes the concept of average height.

Ex 2. where we start with a simple concept (a simple collection of attributes) and draw out other concepts.

- We start with a single concept/term (like height; or numbers). A thesis.

- We draw out at least two contradictions (a duality or a deficiency and excess, like short and tall; or -1 and 1). Antitheses.

- We then define a middle or “golden mean” (like average height; or 0). A synthesis.

- We then can consider degrees (like very short, short, average, tall, very tall; or -1…0…1). A range of degrees.

Here we are doing exactly what we did above, but our system is more complex. Our middle isn’t average height, it is all possible numbers including fractions between -1 and 1 (which is an infinite series).

Ex 3. where we start with a complex concept (a complex system of related attributes/properties, concepts, judgements, beliefs, etc) and draw out one or more antithetical complex concepts:

- We start with a single concept/term (like liberalism). A thesis.

- We draw out at least one contradiction to illustrate duality (like conservatism). An antithesis.

- We then define a “golden mean” between of our thesis and antithesis (like centrism). A synthesis.

- We can then can consider degrees between (like very liberal, liberal, centrist, conservative, very conservative). A range of degrees.

- We can also consider additional antithesis/syntheses (like fascism and communism).

- We can then consider “spheres” and complex relations. In complex systems properties might be shared by two or more systems and different types of each system might exist. For example types of liberalism and types of conservatism share properties (for example social liberalism and classical conservatism share the property “authoritative”).

In all cases we are doing the same basic thing. That is, we are taking a simple or complex concept (an observation of a single attribute like height, or a conceptualization of a complex system of attributes like liberalism), and then we are abstracting out one or more related concepts (simple or complex) using logic and reason.

This becomes important in cases where we want to analyze (in the style of the analytic a priori), and to predict causes and effects.

This is therefore a type of logical analysis and synthesis that uses rationalization, a sort of play on reasoning by contradiction (very much in the vein of deduction). It is a form of reasoning where instead of knowing A and B and deducing C, we only know A and must deduce everything else from that (so a form of deontic reasoning in a way despite its relation to the syllogism).

After we draw out concepts from our thesis, we can apply different forms of reasoning to see if we have drawn out something useful and if our logic was “sound and cogent” so to speak (but, lets put that fact-checking part aside for now and focus on the core concept).

Another way to illustrate the above is like this.

Simple Hegelian Paradigm Example Pertaining to the “Physical” Category Height:

| Thesis | Synthesis (Mean) | Antithesis |

|---|---|---|

| Concept | Difference | Opposite of the Concept |

| Ex. Short; -1 | Average Height; 0 | Tall; 1 |

Simple Golden Mean Paradigm Example Pertaining to Physical Height:

| Thesis | Antithesis of Deficiency | The Golden Mean | Antithesis of Excess |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept | Antithesis 1 | Synthesis | Antithesis 2 |

| Ex. Height; or Numbers | Short; -1 | Average Height; 0 | Tall; 1 |

Abstraction and the Socratic Method: Imagine a conversation about height. One person in the conversation only knows tall, they have no concept of short, thus they have no concept of average height. We cannot have a proper conversation with this person unless we “enlighten them”. We can’t force enlightenment, so we instead will use questions to help them to abstract the concept of short from height themselves (the Socratic method). We can then, with short and tall defined, have a conversation about the ideal average height. By taking the thesis of height, and then abstracting short, average height, and tall, we have created a space in which we can properly deal with the concept of height (we have better defined the true character of height). That simple physical example hardly needed to be said, but when we move onto concepts like moral goodness or justice, the tactic will be vital to understand. See Plato’s Theory of Forms for some related thinking; see also Aristotle’s virtue theory.

An Introduction to the Dialectic Method and the Golden Mean Theory as it Relates to Abstraction

With the example and explainer above covered, let’s return to a basic introduction.

Our main goal on this page will be to use the “the art of abstraction” (the process of drawing concepts out of concepts, the dialectic method, the golden mean theory, and other related theories illustrated in our examples above) to help us examine concepts (terms), deduce logical inferences, create “paradigms,” and illustrate positions related to “the basic categories of human understanding” (physical, logical, ethical, metaphysical) in “the social, political, economic, and other spheres” (in different areas of interest in life).

Or, in other words, on this page we will take a single thesis of any type (take the 1), abstract at least one antithesis (abstract the 2), find a golden mean between (find the 3), consider the spectrum of possibilities created from this (find the many degrees between extremes), and then think of the different ways we can apply logic, reason, and categorization to better understand the relations between concepts related to different aspects of life.

We can use this technique to tell us more about our original concept and to our minds to different and new concepts.

In this respect, we can consider “abstraction” as a form of reasoning where instead of practicing deduction and induction in their classical forms, we abstract new concepts from existing concepts (by considering things like contradictions and dualities).

This exercise in logic and reason will help us to better understand and compare terms, especially in metaphysics and the social sciences where we are often dealing with abstract and complex rationalizations rather than purely physical objects (although we can apply it to both the physical and metaphysical and everywhere in between; for example, we can start with the empirical and working up to the rational, or start with the rational and working down to the empirical, or start with a synthesis and work in both directions).

To do this we’ll use a synthesis of:

- The general concept of duality (from non-being comes being, and in between is change; or in science-ish, from nothingness comes a unified force, comes the four forces, comes the standard model particles, comes the fractal of things we call the universe, which is at its core all essentially massless electromagnetic particles).

- The Hegelian Dialectic (his concept of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis based loosely on Plato’s Dialectic),

- Plato’s Dialectic AKA the Dialectic Method/Socratic Method (Plato’s Socrate’s method of using logic and skepticism in deductive reasoning, as illustrated by the Socratic method, the syllogism, and the concept of non-being, being, and becoming AKA change and difference; or, more simply, the concept of drawing contradictions from definitions),

- Aristotle’s Golden Mean Theory (which shows the “mean between” two antitheses abstracted from a single thesis; generally applied to virtue theory),

- and other related theories that deal with dualities, abstractions, and contradictions (including other theories from Plato and Aristotle; Aristotle’s categories for example, this is all an aspect of “the Categories“).

Or, in the words of the Tao:

When people see some things as beautiful,

other things become ugly.

When people see some things as good,

other things become bad.Being and non-being create each other.

[and knowing this we can practice the arts of abstraction, deduction, induction, combining, comparison, contradiction, etc; non-being and being are at the core of all things, they are the fundamental duality… and “as above, so below,” all things fit this pattern]

In other words, we’ll explore how to find the antithesis of any term that has one (not all terms are of the same “category,” and not all terms have an antithesis) and how to make tables like the one’s below to find both sides of an argument, to better define principles, to categorize knowledge, to find desirable means, and to generally better understand relations like causes, effects, reactions, and changes.

The Logic Behind Abstractions and Dualities: Hegelian Dialectics and Greek Dialectics

In this section we’ll explain the logic behind the abstractions and dualities we have discussed above. We’ll do this by defining and discussing terms related to our process of abstraction in a logical order.

Dialectic: Dialectic is the name given to the discourse between two or more points of view (a thesis and antithesis), which creates at least one “third” balanced point (a synthesis). The terms thesis, antithesis, and synthesis are Hegel’s terms, but the general theory can be understood in Plato’s terms, in Aristotle’s terms, in Taoist terms, or other terms (although it can, we are going to “synthesize” all of these theories). In all cases it speaks to the study of abstractions and dualities (drawing concepts out of concepts).

Clarifications: The concept can be applied in a variety of ways to find new concepts, or to find hidden truths, or to find contradictions with logic and show falsehoods (“reasoning by contradiction;” reductio ad absurdum). With that in mind, we’ll start with the Hegelian Dialectic (the philosophy of the duality of thesis and anti-thesis). The Hegelian form seeks to find truths, not to solely to draw out a contradiction or inconsistency like Socrates would have done with his questioning in Plato’s dialogues.

Hegelian Dialectic + (Hegelian Dialectic with a few considerations): A thesis, gives rise to its reaction, an antithesis. The antithesis then contradicts or “negates” the thesis. Then, the tension between the two is resolved by means of a synthesis (a mean or balance). This is a simple version of what is really happening and is more useful when paired with other theories, but it is a great starting point. Consider, we can start with a thesis and work toward a synthesis, or we can start with a synthesis and work toward a thesis. Whether we flip this on its head, consider the rational, or view this from a purely empirical lens, the concept is the same.

Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis, Abstraction

Thesis: A thesis is any concept (simple or complex, a single attribute or a complex system of concepts, pure formal reason or purely material empiricism). Let’s use the example “liberty” (one of the two main theses or virtues behind the political ideologies Democracy and Liberalism; the other is equality.) We could easily use a physical thesis like height rather than a conceptual thesis, or a thesis from any sphere of human understanding (we just aren’t here).

Antithesis: At least one anti-thesis can be abstracted from [almost] any thesis. So for liberty, an equal opposite is anti-liberty AKA authority. In cases where we are unsure of an opposite, it may be that we are dealing with two or more opposites. For example, we could have also drawn the antithesis anti-liberty. This speaks to the idea that there are different types of antitheses (but let’s put that aside for now). TIP: For another example, from the concept individualism we can create the paradigms “individualism vs. anti-individualism” and “individualism vs. collectivism” (where anti-individualism is not “exactly the same” as collectivism, but both are “opposites” of individualism). These are just different flavors of antithesis, each contradiction/opposite/duality is worth abstracting and considering.

Synthesis: Once we have a thesis and anti-thesis we can abstract one or more syntheses. The synthesis of the ideology of liberty (liberalism) and the ideology of authority (conservatism) can be called [for the sake of an example] Republicanism (it is an ideology that appreciates order and authority, liberty and equality, it seeks a mixed form of temperance). For another example if we have truth and untruth (AKA a falsehood), then in the middle we have a half-truth (a mix of truth and falsehoods). We can then look at types of truths, lies, and half-truths to see there is a spectrum of possibilities. There is at least white lies and blue lies, and from a more broad perspective there is concepts like lies of omission and commission, and misinformation, disinformation, marketing, etc. Just like there isn’t one antithesis, and instead there are different flavors, there are also different flavors of theses and syntheses.[2]

Abstraction: In this sense, abstraction is the art of inferring antitheses and syntheses from theses (or of inferring theses and antitheses from syntheses; any term can be a starting point once we have defined it). Beauty creates ugly (a lack of beauty), and we can call the root thesis beauty. However, short and tall are both abstractions of the concept of length/height (here length is a sort of thesis, and both short and tall are both antitheses, and at best a synthesis is simply middle-size). Like we saw in the examples at the start of the page, there are different flavors of abstraction methods as well.

This brings us to the Golden Mean theory of Aristotle we discussed a bit above and the idea of spheres, first some notes on the above.

Complexity and Notes Before Moving on

Adding Complexity: One reason we want to pair Hegel’s theory with other theories like the Golden Mean Theory is that, as noted, we can abstract more than one type of antithesis and synthesis from a thesis. Thus, things are a little more complex than just “negating” or just “being an opposite” or just “being a difference”. The more complex the starting term, the more ways we can go with this. Consider the thesis collectivism, anti-collectivism is one type of opposite, but individualism illustrates another type of difference. A strict theory might say we should only consider individualism, but our theory wants to find all opposites of a thesis and consider each. Likewise, we want to find all shades in between (even if we do this by defining a single term). More on that below.

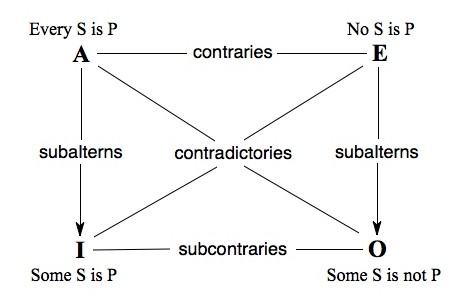

The different types of contradictions (modes of opposition): To add to the above, as Aristotle introduced in his categories, “there are different types of differences.” We can call these relations by different names, but there is no perfect list. The logic will work similar to Aristotle’s square of opposition, where there are “contraries” (such as “black” and “white”) and “contradictories,” (such as “black” and “nonblack”). According to Harold Walsby we can also consider “static” (fixed contraries and contradictions that never change properties) and “dynamic” (contraries and contradictions that change and evolve and can come to share properties over time). [3][4][5]

The following is a diagram for the traditional square of opposition is:

That square’s terms can be understood with the following explanations of versions of contraries and contradictions:

- Two propositions are contradictory if they cannot both be true and they cannot both be false.

- Two propositions are contraries if they cannot both be true but can both be false.

- Two propositions are subcontraries (a type of contrary) if they cannot both be false but can both be true.

- A proposition is a subaltern (speaking loosely another type of contrary) of another if it must be true if its superaltern is true, and the superaltern must be false if the subaltern is false.

For our purposes something similar to this will apply.

Notes on Dialectics and Socialism: This concept is used in Socialist philosophy, for example by Marx. Marx’s Dialectics start with empirical concepts, and Hegel’s start with ideas. Marx thought Hegel was wrong to consider metaphysics (in the fashion of Plato’s forms) as real. I personally think Marx was missing a giant part of the whole theory I am putting down, but to each their own. We will kindly borrow both theories (as they are, for me, mutually dependent; i.e. we can and must move from metaphysics to physics and back again, even if we have to trade between the formal and material) and consider theses of physics, logic, ethics, and morality (crossing forks between these categories of knowledge whenever we can). I suggest you don’t let the proximity of dialectics and Historic Materialism (the theory behind Communism) throw you off. Each philosopher uses this fundamental truism to their own ends. The general concepts works for most any concept (after-all it is a theory of concepts, not politics). Dialectics is all about finding “extreme opposites” or “polar opposites” to define “the bounds” of a concept and to detect middles (or defining middles and working back to find extreme opposites, as we’ll see with the Golden Mean; i.e. we will use analysis and synthesis in our theory of abstractions). Socialism is a rejection of the system that came before it, so it is an anthesis in action, likewise liberalism was an anthesis of the system before it (this is only one of many levels we can apply these ideas).[6][7]

Notes on Plato’s Being, Not Being, and Becoming (Difference): Before getting back into Hegel, I want to introduce Plato’s related theory (as it comes before even Aristotle’s). In Plato’s Sophist (and other works like the Republic) he lays the groundwork for Hegelian Dialectics. Plato’s definition is good, but very broad (he uses the metaphor to explain not only how to abstract, but how to argue). For our purposes the theory works best when we synthesize Plato’s theory with the others. For Plato, being and not-being are used as the main examples of a thesis and antithesis (in a larger discussion of categorizing knowledge and knowing truths). For Plato, Being (that which is), Not-Being (a state of not being that which is), and becoming (AKA “difference”) are our thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Plato eludes that being and not-being are not true opposites or contradictions, but rather two related states that together form a duality. This is just another way to look at the same concept already presented, but notably, this is the tactic Plato’s Socrates uses to argue (he detects a thesis and then makes the other person in the conversation abstract an antithesis via a line of questioning, so they can discuss a synthesis, a “golden mean” of sorts… which leads to more questions). With that in mind, let’s move on to Aristotle’s Golden Mean theory.

TIP: We can muse, “did the egg come first or the chicken?” Or, we can take the taoist approach and consider Yin and Yang as two parts of a whole. Figuring out order of existence is a different subject. Likewise, we can easily consider the nothingness out of which something comes to be a “a thing”. When we move from being to not being we the changing of states is a difference. We can use this analogy to look at truth, things are either true or not, or we can move from “not knowing” to “knowing”… but these are all side conversations.

Spheres and the Golden Mean Theory

Spheres: Any of these models can exist in what we can call spheres. This is like the overarching category that we are consider the dialectic paradigm in. For example we can consider left-right social issues, in the political sphere, and then consider a liberty paradigm in the liberty “sphere” (by placing a paradigm in a sphere it helps give it context and meaning). Complex categories can have overlapping concepts (spheres can overlap and share properties) and a single property can belong to a number of concepts in different spheres (for example “greenness”). That will make sense in one second when we look at the Golden Mean theory.

The Golden Mean Theory: The Golden Mean theory of Aristotle accounts for what the simpler theory above does not, although there is still some complexity to consider beyond this. Aristotle defined vice and virtue as: vice is an excess or deficiency (not one, but two extremes) of virtue, and virtue is the mean between two accompanying vices that exists within a “sphere of action”. For example, in the sphere of “getting and spending”, “charity” is the virtuous mean (the balance) between “greed” and “wasteful extravagance”. If we inherit a fortune, this simple theory tells us that virtue isn’t found in hoarding or wasteful spending, but in a charitable moderation. Thus, if we can define a sphere of action, vice, or virtue we can use this model to fill in the blanks and detect the correct moral behavior. Likewise, we can apply this method to spheres outside of morality (such as governments; see an essay on the types of governments for examples)…. and that is exactly what we are doing here. Ignore the virtue theory for a second, and consider our concept of liberty again (in the charts below).

How is the mean theory like the dialectic method? If we start with a deficiency or excess (an extreme), we can call it a theses and then detect the anti-thesis and then the “mean” is our synthesis. So in that way the Golden Mean and Dialectics are synonymous. However, if we treat our “sphere of action” as the thesis, then we can say we have derived two extreme opposites from a single thesis, and thus the Golden Mean considers an extra element. I am of the mind that the Golden Mean is the best theory for some terms, and binary dialectics the best for other terms. In other words, they aren’t as “different” as they are two ways to look at the same sorts of problems. By looking at a given problem in more than one way we get different “frames of reference” and avoid overly simply conclusions.

Binary example: To bring things back to “simple” for a second: In binary things are either on (1) or off (o) or on/off (01). This is a simple dialectic and simple golden mean, two extremes and one mean, and from that we can create everything we create with computers. There is infinite possibilities between on and off, but we can use just three terms as a foundation.

A Thesis Sphere Example (one of many ways to illustrate this using semantics and symbols):

| Sphere of political action (Thesis) | Conservative Right-Wing (Antithesis of Deficiency) | The Left-Right Balance (Golden Mean / Synthesis) | Liberal Left-Wing (Antithesis of of Excess) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liberty | Favors Authority (Classical Conservatism) – Not Enough liberty. Deficiency of Liberty. | Balanced Liberty | Favors Freedom (Classical Liberalism) – Too much liberty. Excess of liberty. |

| Equality | Favors Individuals (Social Conservatism) – Not enough equality. Deficiency of Equality. | Balanced Equality | Favors Collectives (Social Liberalism) – Too much equality. Excess of equality. |

Paradigms and charting qualities: We can call each row of the charts above a paradigm, these paradigms can then be compared and plotted on tables and charts and the tables and charts themselves can then be analyzed and synthesized.

Terms, Qualities, Properties, and Virtues: All the factors above, in any of their forms, can be called qualities, properties, terms, or virtues (these are all semantic names for elements of a system).

Paradigms and AntiThesis and Synthesis Paradigms: We can then use the above terms to create an “antithesis” paradigm (where in this example we place our Thesis/Antithesis of Deficiency in its own paradigm. You can see how this takes a concept that would be very hard to visual in our heads and turns it into a nice little chart that we can use as a model/a theory.

An AntiThesis Sphere Example:

| SPHERE OF ACTION | Not Conservative Enough / Too Liberal | The Liberal-Conservative Mean | Overly Conservative / Not Liberal Enough |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authority | Overly Liberal | Correct Authority | Overly Authoritative |

| Hierarchy, Order, and Tradition | Extreme equality | Correct Hierarchy, Order, and Tradition | Extreme Inequality |

Our Synthesis in the paradigms above as a concept: Each of the “sphere of action” boxes above can be treated as a thesis, and then each single thesis gets two synthesis (a two-way abstraction), and then our “mean” or “balance” boxes can be treated as a synthesis (alternatively we can consider one of the antitheses a thesis, the other an antithesis, and ignore the sphere). Looking at things this way is more complex than a simple abstraction, but it is much more useful in cases where there is simply more than one extreme of a single concept. We can then pair syntheses to do something really magical. We can abstract or synthesize from this a good ideology, we can from this distill Republicanism from the terms liberty, equality, authority, and Hierarchy, Order, and Tradition with more confidence. We can also see how the syntheses Socialism and Fascism (the extreme responses to liberalism) arose as antitheses reacting to the inequality of the liberal state with extreme equality and extreme authority respectively (TIP: The reality is if you really want to get the political theory behind this this you should check out our page on left-right, this is just laying some groundwork with examples here; we consider maybe 30 different paradigms on our left-right page to examine real in-action political ideologies, and even that list isn’t exhaustive).

Moving Forward: Using Charts and Adding Complexity

Creating spectrums: If we have one position, we can abstract its antithesis, if we have that (with most terms) we can find at least a single mean. However, for more complex terms we can define a large range of means. This range of means is a spectrum! When we compare many related paradigms within a bounded system, we can end up with many complex and related spectrums to consider (this is how it is with left-right). From the simple, arises the complex and we can use analysis to help us move between systems and their properties, simple and complex.

Adding Complexity: So if we use Hegel’s theory and Aristotle’s theory together (sometimes only using one, sometimes applying both as needed) we get a really workable foundation, but there are a few extra notes. First off, to restate this, there is not a finite number of antitheses or syntheses that can be abstracted, and there isn’t really a rule that says we can’t consider mixes in a sort of complex metaphysical alchemic mix. Again, with the example about, if we start with “individualism” we will probably end up abstracting a number of different paradigms, some will be Hegelian, most will be golden means, but we will end up with multiple paradigms (of different types!) to consider. However, when we chart them, even these complex things really end up being pretty simple to work with. What is so hard about looking at the tables above? Nothing, then we just plot them on an XY axis and compare. Like this:

A blank left-right spectrum for those who want one.

Empirical “cheating” and the spheres of human understanding: We can’t touch a liberty, but we can use the process above to find shadows of it on the cave wall. If we know the properties of a thing, we can know a thing, even if we can’t hold it in our hands. When we know properties we can predict reactions, when we know reactions, we can detect properties (we can use analysis and synthesis, deduction and induction). We can both take the empirical and build a “backwards ladder” to better understand logical, ethical, and metaphysic concepts, and we can take intangible concepts and engineer a “forwards ladder” too (taking moral principles and looking for physical, logical, or ethical manifestations). Semantics: Maybe the are both “backwards ladders”, that is just a metaphor anyway.

NOTES: The “four fundamental principles [or spheres, or categories] of human understanding” are: physical (empirical, what is), logical (reason, logic-and-ethics in-thought), ethical (morals-and-ethics in-action), and metaphysical (pure metaphysic morals, or pure philosophy, what should be). When we consider theses, we generally must consider a these that relates to one or more of these categories. We can then consider mixes, for example economy is a mix of the physical and logical spheres, but has ethical implications. If I consider liberty in the economic sphere, it is different than considering liberty in the moral sphere. We hardly need every qualifier noted above to reason simple abstractions… but when you dive into things like left-right politics, you are forced to consider categories, spheres, and other sorts of relations.

Hume’s fork and Kantian Relations: From here it helps to understand different aspects of how things relate to each other. Immanuel Kant laid the “groundwork” for understanding relations between theses in the categories of understanding (or well, the Greeks laid the groundwork, Kant laid the modern groundwork). If you get the basics of Hume’s fork, and then consider how we can relate that beyond just the physical and logical, then you’ll get the basics of how we can understand the relations between concepts (relations like contingent and necessary). That in itself is an essay, so check our our page on Hume’s Fork.

In Summary

So the above isn’t perfect, but what I haven’t said the Tao, the Greeks, and the Enlightenment philosophers basically have already (so its as simple as reading all the history of philosophy and synthesizing it; :D).

Anyway, with the idea that this page needs refinement in mind, we can say.

- Take a single concept (a thesis).

- Then one or more anti-theses can be abstracted (an extreme of excess and deficiency within a single paradigm, or even multiple Hegelian or Aristotelian paradigms that mix spheres and have complex relations for a single term).

- From the anti-theses, one or more syntheses can be made (consider there is infinite fractal dimensions, theoretically between the numbers 0 and 1; that is the “change” Plato and Aristotle talked about, the “difference” between being and not-being, we can express this in logic as 0 and 1 and physics as the nature of particle physics; a golden mean can be expressed as “01”, but the reality is there are infinite terms between (0…1) (see also fractal dimensions and how quantum physics works).

- We can display our above findings as paradigms, denoting the categories in which these paradigms exist, and considering other spheres and complex relations. This helps give a visual model.

- We can than compare, contrast, analyze, and synthesize paradigms, creating charts, comparing charts, and synthesizing that.

- We can use this to learn more about incorporeal forms from the four areas of human understanding. Where we can’t have certainty, for example in the ethical and metaphysics spheres, we can approximate and use analogies. We don’t have to know something for 100% certain to have useful knowledge that works… that is sort of what the whole scientific method is about.

TIP: A good example of that semi-word salad is our theory on left-right politics, as we essentially use this method to define what I consider to be a fairly upstanding left-right spectrum. Want to see another example of what this sort of thinking can create? We use it liberally on our site, so there are many examples, but see “Progressive Centrism” for a specific example.

- Dialectic

- Categories of Lies – White Lies, Grey Lies, and Black Lies Categories of Lies White Lies, Grey Lies and Black Lies

- Aristotle’s square of opposition

- Golden mean (philosophy)

- Harold Walsby: Three Types of Contradictions

- Examples Of Dialectics (Abstracted Compilation) 1959

- What are some examples of dialectical thinking?